In the ancient Jewish world, the Temple was the center of Jewish practice. It was God’s home on earth, and also the place where Jews worshiped God through song, prayer and especially sacrifices. Everything in the Temple — from the tools used to the priests and Levites who ran the place to the pilgrims who came to celebrate festivals to the animals being slaughtered — had to be ritually pure, meaning fit for God. To avoid bringing impurity to the Temple, Jews engaged in many rituals of purification, including immersing in the mikveh.

Given that people, animals and objects needed to be pure to perform divine service, many find it counterintuitive when they first learn that the rabbis considered books of Scripture — the Tanakh — to impart impurity to the hands. Wouldn’t the words of God be kept in a safe place and considered pure?

It’s not that the sages thought the books themselves were impure, but that they rendered the hands of those who touched them impure. This stricture meant that one had to think carefully before touching the books. It is also likely one reason that, to this day, Jews use a yad, a special pointer tool, to touch a sefer torah, a ritual scroll of the Torah — and not bare hands.

Why would the rabbis have ruled that sacred books defile the hands? The answer is actually quite similar to the reason that Jews use a yad today: to preserve them and keep them clean. We know that the ancient Temple contained not only the original tablets of the Ten Commandments, stored away in the Ark of the Covenant which was given place of pride in the Holy of Holies (the Temple’s most sacred chamber) — it also contained a library of all the scriptures of the Jewish people. In fact, by the time of the Second Temple, the Ten Commandments were lost (though some imagined they were hidden under one of the flagstones of the Temple — see Shekalim 16), and only the library of scrolls remained.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Priests who were in charge of carrying sacrifices (many of which became priestly food) had to maintain pure hands to do so. By ruling that holy books cause hands to become impure, the sages created a deterrent so that the priests would avoid eating or bringing food into the rooms with the holy books. This, of course, kept them observing the librarian’s number one rule: No eating in the stacks!

This explanation basically follows Rabbi Mesharsheya in the Babylonian Talmud (Shabbat 14a). But not everyone agreed with this practical though counterintuitive ruling. It was the subject of a major debate in the first century. Mishnah Yadayim 4:6 reports that the Sadducees (a sect from Second Temple times) cried out against the Pharisees (another sect from whom the rabbinic movement evolved) for saying that “Holy Scriptures make the hands impure, but the books of Homer don’t make the hands impure.” If Rabbi Mesharsheya’s assumption about concern for damage to the books is correct, then apparently, the Pharisees didn’t care if worms and mice ate copies of Homer.Since the language “causes the hands to become impure” was associated with holy books, the rabbis after the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE continued to use the phrase to describe which books were holy and conversely which books were not holy (the “not holy” books do not make hands impure). Understanding this can help us to decode the debate over whether to include two later biblical books in the canon at all.

Should Song of Songs and Ecclesiastes Be Part of the Bible?

By the time of the rabbis, much of the Bible was fixed. The Torah had found more-or-less its final form many centuries before, in the time of Ezra and Nehemiah (finds from the Dead Sea Scrolls offered scholars confirmation of how little the Torah changed over the centuries). The writings of the Prophets, too, were largely all accepted as canon. But other books, those that would go in the Writings (Ketuvim) the third and final collection of the Tanakh, were still subject to debate. In particular, the sages worried about include two books that seemed both irreligious and dangerous: Song of Songs and Ecclesiastes.

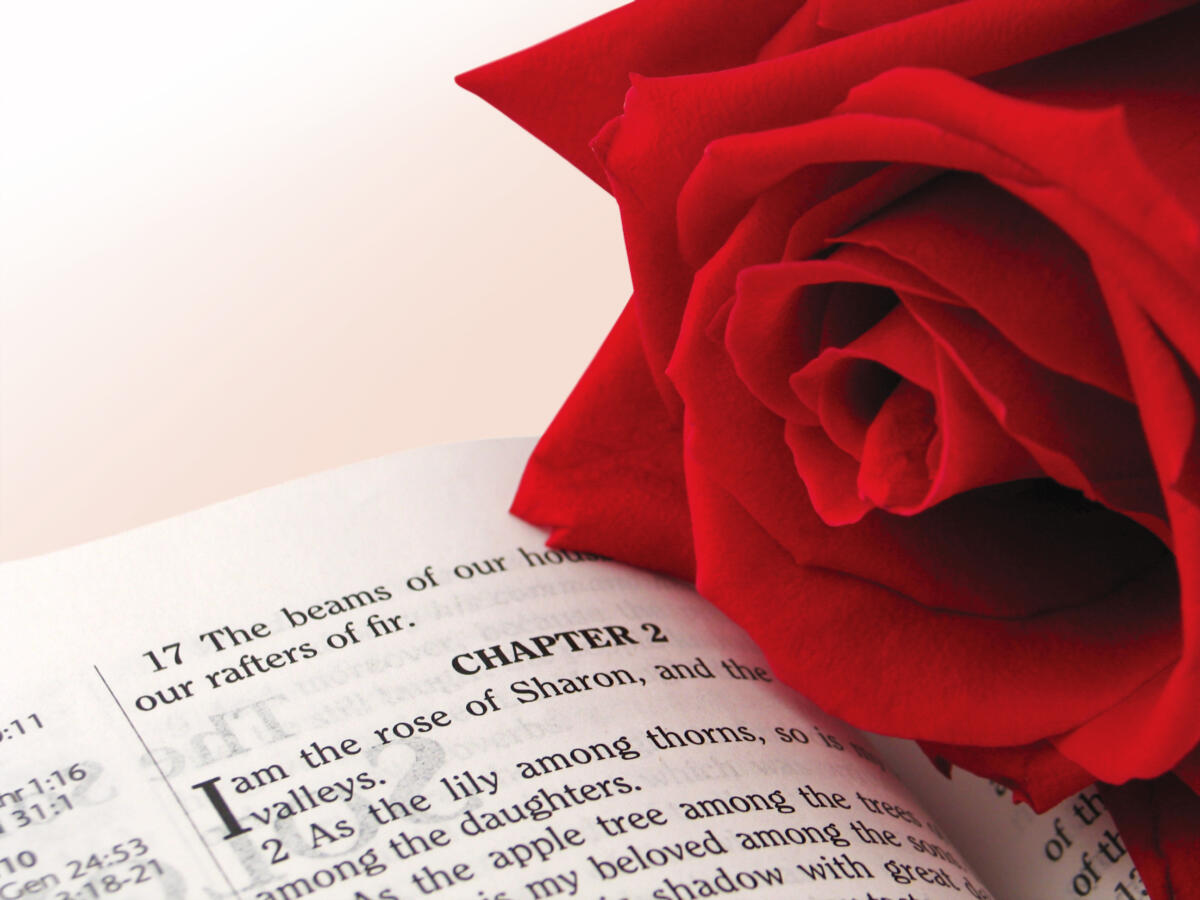

Song of Songs is a beautiful and, on the surface, completely secular love poem written in charged, erotic language. It was a big hit in the ancient world. But was it sacred scripture?

Ecclesiastes similarly unnerved the sages. Arguably one of the first existential Jewish texts, Ecclesiastes famously declares that “all is hevel (variously translated as vanity, nothingness, vapor)” and warns people that there is little more they can do in life than enjoy its pleasures before heading back to oblivion. A later postscript on the book (Ecclesiastes 12:14) declares “The sum of the matter, when all is said and done: Revere God and observe His commandments! For this applies to all mankind.” But this pious ending is unlikely to be original.

Nonetheless, Rabbi Akiva, one of the most influential and famous sages of the rabbinic era, argued strenuously for the inclusion of both Song of Songs and Ecclesiastes in the Hebrew Bible. Here is the sages’ record of the debate:

All the holy writings make the hands impure. The Song of Songs and Ecclesiastes make the hands impure.

Rabbi Yehudah says: The Song of Songs makes the hands impure, but there is a dispute about Ecclesiastes.

Rabbi Yose says: Ecclesiastes does not make the hands impure, but there is a dispute about the Song of Songs.

Rabbi Simeon says: Ecclesiastes is one of the leniencies of Bet Shammai (who say it does not make the hands impure) and one of the stringencies of Bet Hillel (who say it does make the hands impure).

Rabbi Simeon ben Azzai said: I received a tradition from the seventy-two elders on the day when they appointed Rabbi Eleazar ben Azariah head of the court that the Song of Songs and Ecclesiastes make the hands impure.

Rabbi Akiba said: God forbid! No one in Israel ever disagreed about the Song of Songs by saying that it does not make the hands impure. For the whole world is not as worthy as the day on which the Song of Songs was given to Israel; for all the writings are holy but the Song of Songs is the holy of holies. So if they had a dispute, they had a dispute only about Ecclesiastes.

Mishnah Yadayim 3:5

Remarkably, Rabbi Akiva not only declares that the erotic and apparently secular love poetry of Song of Songs is sacred scripture — he labels it the most sacred, likening it to the Holy of Holies in the Temple. This extraordinary declaration highlights the aural similarity between these two doubled nouns, Song of Songs (Shir HaShirim) and the Holy of Holies (kodesh kodashim). In the original Hebrew, Akiva’s declaration is lyrical.

Rabbi Akiva won this debate, and both Song of Songs and Ecclesiastes entered the Jewish Bible. They are both ascribed to Israel’s ancient wise king, Solomon (along with the Book of Proverbs) and they are also read in synagogue every year, Ecclesiastes on Sukkot and Song of Songs on Passover. The loving relationship of Songs of Songs was reinterpreted as a metaphor for the ardent love between God and Israel, on display most dramatically during the holiday that recalls the Exodus from Egypt. Some Jews also read Song of Songs every Friday night, as a kind of renewal of the vows between God and Israel. As Rabbi Akiva passionately argued, it has become a permanent part of the Jewish canon.

Mishnah

Pronounced: MISH-nuh, Origin: Hebrew, code of Jewish law compiled in the first centuries of the Common Era. Together with the Gemara, it makes up the Talmud.