The books of Ezra and Nehemiah are the only completely historical books in the third section of the Hebrew Bible, the Ketuvim (Writings). In English Bibles, they are usually split into two, with the book of Nehemiah appearing as a separate book from Ezra, but in the Hebrew tradition, they are one book, entitled “Ezra,” and Nehemiah is simply the second part of Ezra. In this essay, the term “Ezra” is used to describe the complete book.

Read the books of Ezra and Nehemiah in Hebrew and English on Sefaria.

Parts of Ezra are written in Aramaic, which was the common language of the Middle East at the time (Ezra and Daniel, which is also partly in Aramaic, are the only books of the Hebrew Bible that are not completely in Hebrew). Ezra is chronologically the last historical book in the Hebrew Bible, covering the end of the sixth and the beginning of the fifth centuries B.C.E. It tells the narrative of the return to Zion.

What Was the Return to Zion?

At the end of the sixth century B.C.E., the kingdom of Judah was dismantled by the Babylonian empire. Jerusalem and the Temple (the Beit Hamikdash) were destroyed, and thousands of Judahites were exiled to Mesopotamia. Those who were exiled, however, did not see this as a final stage in Israel’s history. They were aware that Jeremiah had prophesied that there would be an exile, but there would also be a return (chapter 32, especially vv. 26-44).

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

The opportunity for that return came about in 538 B.C.E. The Babylonian empire fell, and the Persian empire gained control of Mesopotamia and most of the Middle East. One of the first rulers of the empire, Cyrus, sought to show tolerance to all of the communities in Mesopotamia. Cyrus issued a famous edict, narrated at the very beginning of the book of Ezra, allowing Jews who wished to return to “Jerusalem that is in Judah” and build a “House for the God of Heaven” to do so.

Three Stages, Two Main Issues

The book of Ezra tells of the three distinct stages in the return, and of the challenges and practical difficulties that the returnees faced at each stage. Not all the Jews in Mesopotamia were interested in returning to Zion. Those who did were fired by the hope of building a society which would restore Israel’s ancient glory.

The two central issues in building this society were:

1) The attempt to define the boundaries of the society’s members. “Who was a (true) Israelite?” was an issue of great concern. This can be seen from the lengths to which several chapters in the book (Ezra chapter 7, Nehemiah chapter 7) go in listing the names of the returnees according to their ancestral families: Priests, Levites, members of the tribes of Judah and Benjamin.

2) The attempt to turn the laws of the Torah into the laws of the society. The expression “It shall be done as in the Torah” appears for the first time in the Bible in Ezra 10:3, and it is during this period that we find the first narration of a public reading of the Torah, in Nehemiah chapter 8. Some have argued that the Torah was promulgated by Ezra, but it is clear that at least most of the text of the Torah existed during the first Temple period.

The First Wave: Zerubbabel

The first wave of returnees, whose story is told in Ezra chapters 1-6, consisted of about 40,000 individuals (Ezra 2:64), led by Zerubabbel, a descendant of King David, and Joshua son of Jozadak the high priest. Fired by the vision of restoring the glory of the age of David and Solomon, the returnees sought to re-establish the Temple, and to run the community in a way that would elicit divine approval.

As the first Sukkot festival in the land of Israel approached, the returnees reinstated the sacrificial offerings at the site of the Temple, and then began rebuilding the Temple itself (Ezra chapter 3). But the returnees were not the only group to see themselves as heirs of ancient Israel. When the returnees came back to the land of Israel, they found another group already living there, viz. the inhabitants of Samaria and central Transjordan (ancient Ammon).

These Samaritans were, in the view of leadership of those returning from Babylonia, merely the descendants of people brought to the Land of Israel by the Assyrian kings at the end of the eighth century in place of the Israelites they deported. The Samaritans, on the other hand, had Israelite names in some cases, and saw themselves as heirs of the Northern Kingdom of Israel. They objected to the returnees’ building the Temple on their own and demanded a part in the project.

The returnees did not see the Samaritans as legitimate heirs of ancient Israel, and felt they should take no part in the rebuilding, especially since the Samaritans had no connection with Jerusalem. Angered by the returnees’ refusal to include them in building the Temple, the Samaritans lobbied the Persian empire to stop the project; the story of their correspondence with the Persian administration is recorded in Ezra 4. This episode illustrates another aspect of the recurring problem of defining the boundaries of Israelite identity.

The Second Stage: Ezra

The second stage of the return was headed by Ezra, a scribe from a priestly family. Defining who was a member of the community was also an important issue under Ezra. The first problem that confronted Ezra, when he arrived in Jerusalem, was that “the people of Israel, the priests and the Levites, have not separated themselves from the people of the land…they have taken from their daughters for themselves and for their sons, and mixed the holy seed with the peoples of the land” (Ezra 9:1-2).

Ezra reacted strongly to this news: He tore his clothes as a sign of mourning, and prayed and fasted as a sign of repentance. Ezra’s reaction is easy to understand: the returnees believed that the kingdoms of Israel and Judah were destroyed because their inhabitants did not live up to God’s laws, and Ezra was determined to avoid a similar fate for the new society they were building. (Intermarriage with the inhabitants of the land is forbidden, according to Deuteronomy 7:3).Therefore, the laws of the Torah had to become the blueprint for the new society. Ezra convinced the people to begin a process of separating from non-Israelite wives, but the process “was longer than one day or two days’ work” (Ezra 9:13); and it is doubtful if the process was ever completed.

The Third Stage: Nehemiah

When the third stage of the return took place, the issue of intermarriage came to the forefront once again. The leader of the third stage of the return was Nehemiah, a high official in the Persian imperial administration, of Jewish ancestry, who was seized with a desire to ameliorate the physical condition of Jerusalem and of its Jewish community.

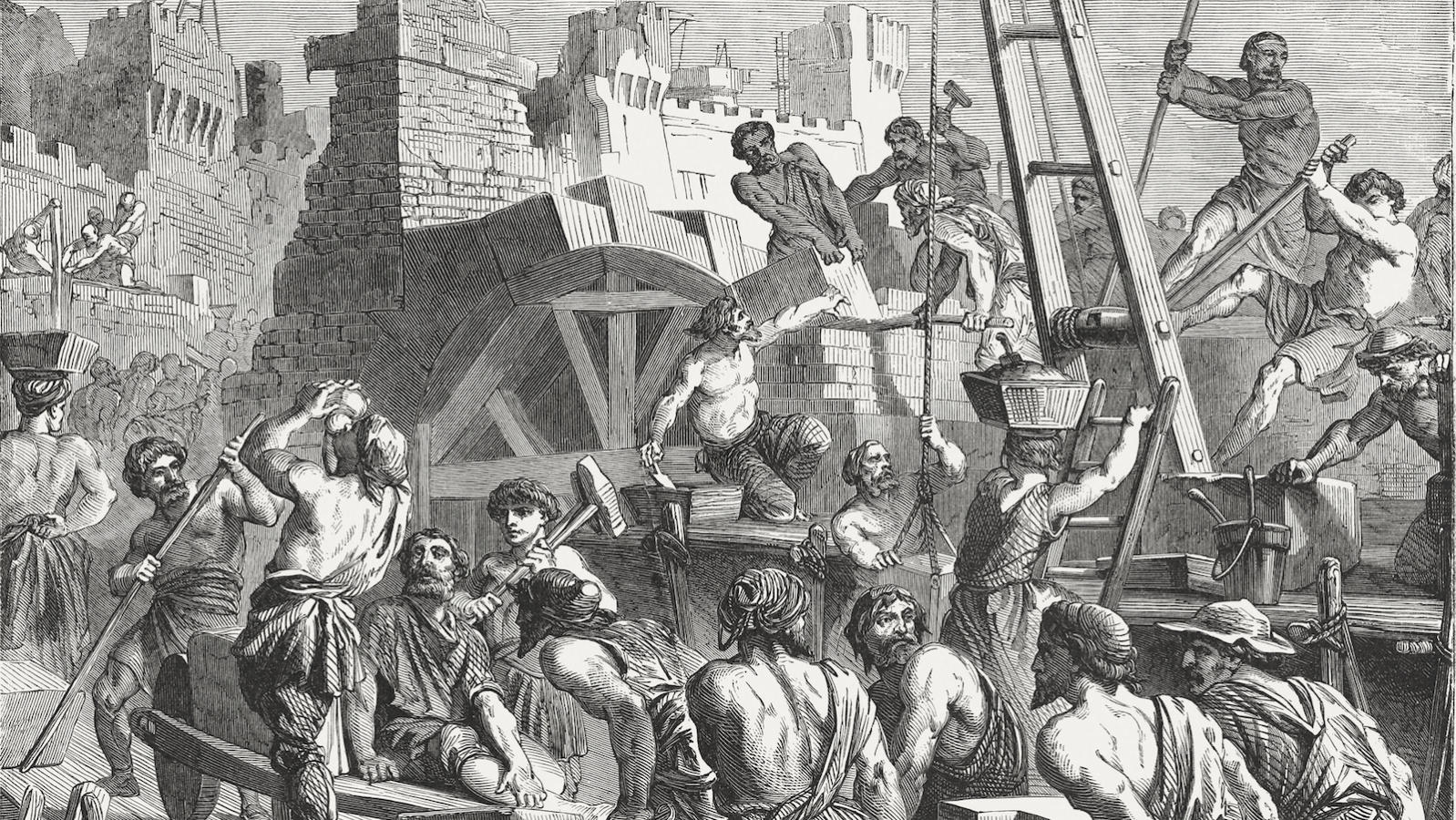

Against threats of war from the Samaritans and the Ammonites, who did not want to see Jerusalem become the political centre of the land, Nehemiah rebuilt the wall of Jerusalem. The builders “built with one hand, while holding daggers in the other” (Nehemiah 4:11), building during the day and guarding the wall at night (Nehemiah 4:16). But Nehemiah did not deal only with the physical problems of the community. He fought with the community’s leaders over their non-Jewish wives (in Nehemiah chapter 13).

In explaining his objection to intermarriage, Nehemiah does not only see intermarriage as a violation of divine law. He speaks about the practical consequences of intermarriage, and mentions two points: 1) Intermarriage challenges the ethnic identity of the community, and erodes its sense of peoplehood. Nehemiah complains (Nehemiah 13:21) that the children of intermarried couples are unable to understand Hebrew, a basic requirement for being a member of the returnees’ Jewish community. 2) Intermarriage challenges the religious identity of the Jewish member of couple: Solomon, beloved of God, was led by his gentile wives to worship their gods (13:26).

Victory and Disappointment

Ezra and Nehemiah tell a frustrating story. In many ways, the reality of the return to Zion did not measure up to the returnees’ expectations. The temple they rebuilt was smaller and far less glorious than Solomon’s had been, and religious challenges such as intermarriage and resistance to Shabbat observance vexed their leaders. But the persistence and doggedness with which the Jews of the period confronted these challenges became a model for the generations that followed. “Rabbi Tarfon said: “It is not incumbent on you to finish the work, but nor are you free to desist from it.” (Mishnah, Avot, chapter 2.)

The prophets who spoke about the period of the return, whose prophecies are recorded in Isaiah 40-66, and in the books of Zechariah, Haggai, and Malachi, dealt with these challenges not by denying the returnees’ grandiose hopes, but by prophesying “delayed fulfillment.” Someday, Jerusalem’s victory “will go forth like brightness, and its salvation will burn like a torch” (Isaiah 62:1). Someday, “the glory of this later temple will be greater than that of the first” (Haggai 2:8). Someday, but not immediately.

Shabbat

Pronounced: shuh-BAHT or shah-BAHT, Origin: Hebrew, the Sabbath, from sundown Friday to sundown Saturday.

Sukkot

Pronounced: sue-KOTE, or SOOH-kuss (oo as in book), Origin: Hebrew, a harvest festival in which Jews eat inside temporary huts, falls in the Jewish month of Tishrei, which usually coincides with September or October.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.