The Hebrew Bible, also known as Mikra (“what is read”) or TaNaKh, an acronym referring to the traditional Jewish division of the Bible into Torah (Teaching), Nevi’im (Prophets), and Ketuvim (Writings), is the founding document of the people of Israel, describing its origins, history and visions of a just society.

The word Bible, from the Greek, ta biblia, is plural and means “books.” This reflects the fact that the Bible is actually a collection of individual books (such as Genesis, Exodus, Isaiah, Song of Songs, and many others). Similarly, another traditional name for the Torah, Chumash (“of Five”), indicates that the Torah itself is a book composed of five books.

The Book is Actually Many Books

Perhaps our conception of the Bible as one book is a result of our having one-volume printed Bibles; in ancient times, individual books were published in smaller scrolls; the word Bible, however, comes from the Greek ta biblia, which is plural and means books. Even the individual books can include a variety of different genres of writing—narratives, poetry, legal texts, prophecies—which makes reading the Bible as a unified book that much more difficult.

Collecting the books and deciding which ones were to be included as part of the Bible and which were not is called the process of canonization; canonization of the Hebrew Bible was concluded during the first century CE. We have fragments and significant portions of the Bible from before that time, but our earliest complete manuscripts date from the ninth century CE and later; remarkably, through hundreds of years of transmission, the received text, what we call the Masoretic text, differs only slightly from those earliest fragments.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

The Contents of the Bible

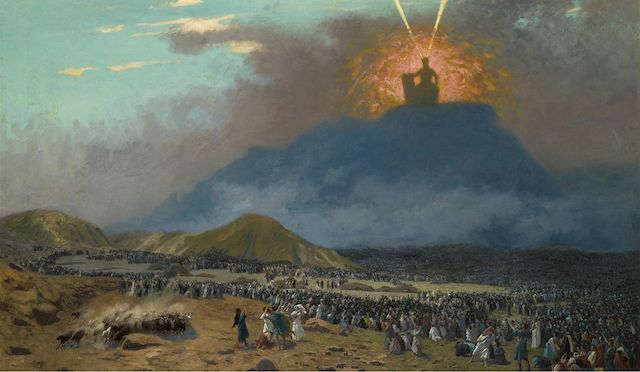

The Torah, or Five Books of Moses, retells the story of how the family of Abraham and Sarah became the people of Israel, and how they came back from exile in Egypt, under the leadership of Moses, to the border of the land of Israel, on the way stopping at Mount Sinai for the revelation of what are known as the Ten Commandments. The Torah includes both the narrative of the formation of the people of Israel and the laws defining the covenant that binds the people to God.

The Prophets is itself divided into two parts. The former prophets — including the books of Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings — are narratives that explain the history of Israel from the perspective of Israel’s fulfillment of God’s covenant. The latter prophets — including Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel, along with 12 minor prophets — report the exhortations of these fiery leaders to return to God and Torah.

The Writings include poetry (Psalms and Lamentations) and wisdom literature (Proverbs and Ecclesiastes), short stories (Esther), and histories (Ezra-Nehemiah and 1-2 Chronicles).

Commentaries

Through the tradition of ongoing commentary, the laws, narratives, prophecies, and proverbs of the Bible find contemporary and eternal meaning. Classical commentaries like those of Rashi, Radak and Ibn Ezra show nearly as great a diversity in style and approach as more contemporary commentaries.

Who Wrote the Bible?

Where did the Bible come from? Traditionally, Jews have claimed that all five books of the Torah were revealed to Moses on Mount Sinai. The prophets were the authors of their own books as well as others that are attributed to them (Lamentations is attributed to the prophet Jeremiah), and Kings David and Solomon each wrote several works (eg. Psalms is attributed to King David).

Internal contradictions as well as shifts in language and outlook have convinced many modern scholars that the Torah and later historical narratives, as well as the books of the prophets and some of the writings, had multiple authors or redactors who edited traditional materials together, leaving some of the seams between the sources. Some of the critical theories that break apart the Bible into its various sources were initially suggested by Christian theologians who used their arguments to advance claims that later Judaism was a corruption of early biblical religion. Since that time, however, many Jewish scholars have integrated the insights drawn from a critical approach; a Redactor or Redactors (known as “R”) may have edited together different sources, but contemporary Jewish scholars may understand “R” (whether singular or plural) as standing for Rabbenu, our Rabbi and teacher.

How to Study the Bible

The Bible is not a difficult book to begin learning, although its complexity makes it difficult to master. A biblical narrative does not stand on its own; some contemporary literary theorists of the Bible take their lead from the Midrash and read the Bible as a whole, reading how parts of the Torah reflect on other parts, and how the Prophets and Writings similarly refer to earlier narratives and laws. From a canonical perspective, reading the book of Exodus is a first step; reading how the prophet Ezekiel retells the story of the Exodus is a next step. Reading the scroll of Esther is a first step; rereading the story of Joseph to tease out the similarities is a next step.

Similarly, one can read the Bible in the context of the cognate literatures that grew up in a similar ancient Near Eastern environment. How is the Noah story similar to or different from the Gilgamesh epic? How are the laws of Exodus similar to and different from Hammurabi’s code?

Or one might read the Bible in light of the ongoing search for a life of sanctification and redemption, as the Rabbis did. How does the Bible relate to Jewish theology or religious practice? One can study the Bible from a variety of different perspectives — literary, historical, anthropological, theological; as the rabbinic sage Yochanan Ben Bag Bag said, “Turn it, and turn it, for everything is found within it.”

By turning our study of the Bible through the many and varied approaches adopted by Jews and non-Jews throughout the generations, we gain a valuable perspective on the Bible itself. By examining the various readings of the Bible, we also gain perspective on the diversity of human cultures that have sought to interpret the Bible.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.