Since Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, is a day of communal prayer and self-deprivation, the observance of the holiday is centered within the community. The first prayer service of Yom Kippur actually takes place immediately prior to sunset on the evening of Yom Kippur. This service is called “Kol Nidrei,” which means “all vows.” These are the first words of a legal formula that is recited at the beginning of this service and chanted three times.

The origins of Kol Nidrei can be traced to the fact that at various times in Jewish history Jews were forced to convert to other religions on pain of death. However, after the danger had passed, many of these forced converts would want to return to the Jewish community, in spite of their forced oaths of loyalty to other faiths. Because of the seriousness with which the Jewish tradition holds words and promises, the Kol Nidrei formula was developed in order to enable forced converts to return and pray with the Jewish community, absolving them of their vows made under duress. This ancient ceremony is an especially solemn and moving introduction to the holiday evening service of Yom Kippur. Even those most estranged from the Jewish community will return on this one evening a year in order to hear the age-old chant.

Symbolizing the spiritual purity toward which we strive, it is traditional to wear white clothes on Yom Kippur, and many people wear a white robe-like garment called a kittel. In addition, Yom Kippur is the only day of the year when one wears one’s tallit (prayer shawl) all day, rather than just in the morning.

Yom Kippur prayer services are characterized by their emphasis on the two major themes of forgiveness from sin and of teshuvah, or repentance. Sin is not viewed as a permanent state in Judaism. On the contrary, it means that we are challenged to repent and improve ourselves. God forgives us for the sins against the divine. In order to stand before God on Yom Kippur ready for true repentance, we must have first apologized and sought forgiveness from those whom we have hurt over the course of the previous year. Only then are we truly prepared to repent before God on Yom Kippur.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

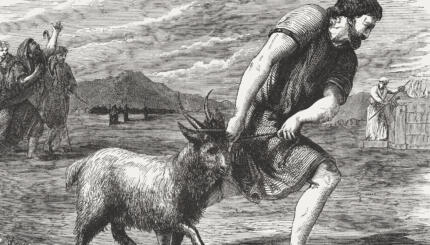

Beginning with Shachrit, the morning service, the themes of seeking forgiveness for sin and engaging in the process of teshuvah form the core of the liturgy. The Torah reading details the ancient Yom Kippur ritual in which a scapegoat would symbolically carry the people’s sins into the desert (Leviticus 16). The Haftarah, or prophetic reading, is taken from the book of Isaiah (Chapters 57 and 58), in which the prophet criticizes the religious rituals of the ancient Israelites when they are not accompanied by acts of righteousness, charity, and morality.

One of the central aspects of the liturgy of Yom Kippur is called the Viddui, or “confessional.” In these prayers, the community recites a list of different transgressions it has committed, literally from A to Z. [Since the viddui is actually in Hebrew, the list of sins follows the Hebrew alphabet, from aleph to tav.] Since no one single person has committed all of these sins, the confessions are in the plural, in order to indicate that we as a community are collectively responsible for one another. When reciting the lists of sins, it is customary to softly beat one’s breast in a symbolic act of self-remonstration.

Two other additions to the Yom Kippur liturgy are the Martyrology and the Avodah service, both of which are found in the Musaf (“additional”) service. The Martyrology is actually a long medieval poem that describes in painfully gruesome detail the deaths of famous rabbis during ancient Roman persecutions. This poem and subsequent additions from the time of the Crusades and (in some communities) the Holocaust are intended to impress upon us the spiritual devotion of our ancestors, in addition to intensifying the religious and emotional tenor of the day. This is followed by the Avodah (“worship”) service, which describes the rituals enacted on Yom Kippur in the Jerusalem Temple in antiquity, when the high priest would enter the Holy of Holies to utter the name of God at the height of the atonement rituals. [Throughout the service, as we recount our transgressions, there is also a constant reminder in the liturgy that despite our sins, God has shown unwavering compassion and mercy towards us.]

The Musaf service also repeats the main themes of the Shaharit service and includes many ancient and medieval religious poems. After the afternoon Torah reading, the Haftarah is the Book of Jonah, whose well-known story of the prophet swallowed by a huge fish deals entirely with the theme of repentance.

The final service of Yom Kippur is unique to the day. Called Neilah (“closing”), it refers to the symbolic closing of the gates of heaven and the book of life, in which God inscribes the fate of each person for the coming year. There is a sense of spiritual urgency that characterizes this service, as the sun is beginning to set and most people are light-headed and exhausted from the fast and prolonged prayers. For a lengthy portion of Neilah, the doors of the Ark are opened, revealing the Torahs inside. It is customary to stand whenever these doors are opened.

Neilah builds in intensity until it concludes with a final tekiah gedolah, a “great blast” of the shofar, the ram’s horn. This awe-inspiring sound signals the conclusion of the Day of Atonement, after which it is customary to prepare or attend a festive break-the-fast meal.

Haftarah

Pronounced: hahf-TOErah or hahf-TOE-ruh, Origin: Hebrew, a selection from one of the biblical books of the Prophets that is read in synagogue immediately following the Torah reading.

teshuvah

Pronounced: tuh-SHOO-vah, (oo as in boot) Origin: Hebrew, literally “return”, referring to the “return to God” teshuvah is often translated as “repentance.” It is one of the most significant themes and spiritual components of the High Holidays.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.

Yom Kippur

Pronounced: yohm KIPP-er, also yohm kee-PORE, Origin: Hebrew, The Day of Atonement, the holiest day on the Jewish calendar and, with Rosh Hashanah, one of the High Holidays.