With the High Holy Days approaching, the themes of repentance and atonement take center stage.

I’m guessing many people find the concept of repentance to be a pretty reasonable one. You take a look at how you’ve behaved over the past year, reflect on what you accomplished, regret the things you didn’t, and recommit to do better next year. It’s basically a new year’s resolution, but set during the Jewish new year season.

But atonement? Not so much.

The word itself breaks down to at-one-ment, meaning the state of being at one with God. It is used to describe the resolution of sin, the Hebrew word for which is kapparah or kippur, as in Yom Kippur. Notions of sin and atonement strike tend to strike the modern ear as arcane, and far less relevant than the personal improvement gloss we put on repentance.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

But I would argue that atonement may be the most underrated Jewish concept. In explaining why, it’s helpful to consider an interesting claim by historian Wilfred McClay, who argues that the modern period has triggered a sort of malaise. Many people, reflecting on all that’s wrong in the world, feel a sense of responsibility or even guilt. But while people still feel a strong sense of right and wrong, they lack a road map for how to resolve it and experience the catharsis of feeling at peace with the world. However many therapy sessions we attend, that guilt just won’t go away. (Just ask Sigmund Freud or Larry David. Jewish guilt is alive and well.)

McClay argues that premodern society had a series of technologies people could use to cleanse this feeling of wrongdoing and resolve one’s conscience. These technologies were traditional religious rituals of atonement, whether Jewish, Christian, or otherwise. Absent these rituals, we find it difficult to rid ourselves of guilt.

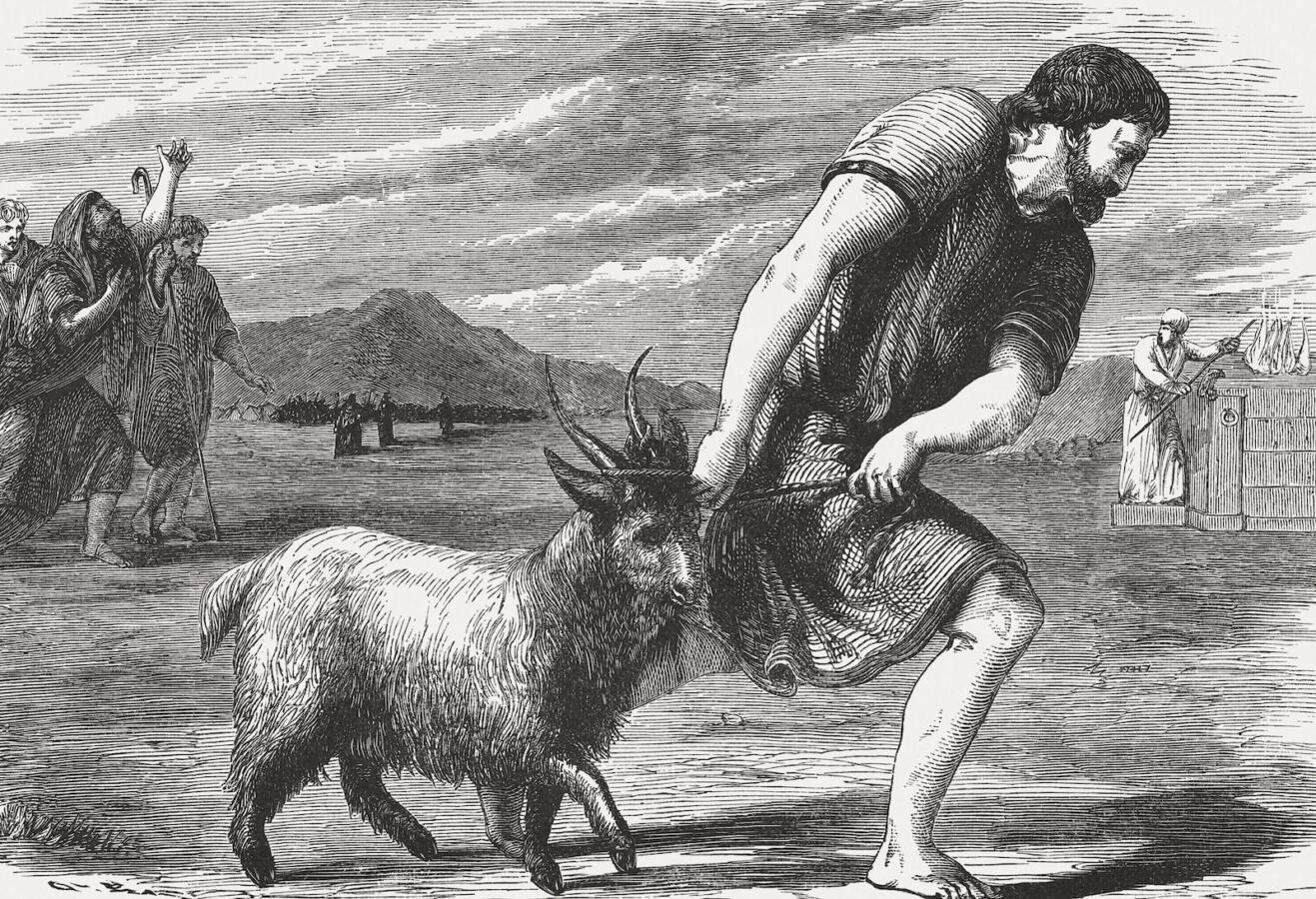

When we trace these rituals to their source, we find something fascinating. The Hebrew Bible features an extensive account of how sacrifices — both individual and communal — are brought to resolve sin. The most extensive of these sacrifices are brought on the Day of Atonement, with one goat sacrificed in the innermost part of the Temple and its counterpart sent far away into the desert, both yielding atonement for Israel’s sins. When discussing this atonement, the Bible uses a variety of metaphors — the wiping away of a stain, the removal of a heavy burden, the repayment of a debt. But whatever one’s metaphor for sin and its resolution, experiencing the righting of a wrong is significant not only on ritual grounds, but as part of human phenomenology.

So what happens now that the Temple has been destroyed? If sacrifices can no longer be brought, how can the Jewish people, both individually and communally, achieve atonement?

One view, which seems to come out of a straightforward reading of the biblical passages that predict the destruction of the Temple, is that Israel has lost its ability to easily effect atonement. To which the rabbis of the Talmud had a radical response: In the absence of the Yom Kippur sacrifices, the day itself serves to atone. Moreover, some rabbis argue that even those who do not repent, and maybe even those who reject the concept of the Day of Atonement altogether, are atoned as well.

This idea implies the idea of a God of grace, who one offers resolution of guilt to those who do not deserve it or even ask for it. Instead of the destruction of the Temple signifying that God has abandoned Israel, God has embraced Israel.

Today, we mark the Day of Atonement not with sacrificial rituals but with ritual prayer. We recall our wrongdoings and regret them. We promise to do better.

But we also reach out to the divine source of grace beyond ourselves. Much of the traditional Yom Kippur liturgy relates the process of the atonement rituals that used to take place in the Temple, involving goats, blood, and the cleansing or sending away of sin. By recalling these unusual rituals Jews once performed, and asking that God resolve our sins on Yom Kippur, we embrace the role of ritual in achieving the catharsis of atonement. We allow that process to take place not only metaphysically, but in our self-perception, as well.

The High Holy Days are important for the opportunity they provide for us to repent and improve ourselves to the extent we can. But they are equally important for teaching us that, at some point, we need the grace of God to fully resolve our guilt.

This article initially appeared in My Jewish Learning’s Shabbat newsletter Recharge on September 24, 2022. To sign up to receive Recharge each week in your inbox, click here.