Sefer Ha-Zohar (The Book of Radiance) is a mystical Torah commentary written in Aramaic. It comprises multiple volumes totaling over 1,000 pages.

It is part of the corpus of the Jewish mystical tradition known as Kabbalah, though it is not the first work of that tradition, a distinction that belongs to the 12th-century Sefer ha-Bahir, The Book of Brilliance. (The first Jewish mystical text is Sefer Yetzirah, though this is not technically part of the kabbalistic tradition.) The Zohar, however, is now one of the better-known works of kabbalistic literature, thanks to the early 20th-century scholarship of the German-born Israeli philosopher Gershom Scholem and to recent English translations. Though difficult to understand, due to the dense and obscure cosmological system the text inhabits, even in translation, the Zohar invites those willing to explore it into a fantastical universe filled with spiritual contemplation and insight.

Who Wrote the Zohar?

According to traditional Jewish belief, the Zohar was revealed by God to Moses at Sinai, and passed down orally until it was written down in the second century by Rabbi Shimon bar Yohai (known as the “Rashbi,” also sometimes referred to as Simeon ben Yohai). From a historical-critical perspective, the authorship of the Zohar has been a matter of debate for centuries.

Scholars now agree that it was written in 13th-century Spain, likely by the Castilian kabbalist Rabbi Moshe (Moses) de Leon and multiple other authors. The text was apparently written in Aramaic, not a widely used language at the time, in order to create the appearance of having been authored centuries earlier.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Major Themes of the Zohar

Some major themes in the Zohar include the nature of God and the cosmos, the creation of the world, the relationship of God to the world through the sefirot,(attributes of God), the nature of evil and sin, the revelation of the Torah, the commandments, holidays, prayer, rituals of the ancient Temple, the figure of the priest, the experience of exile, and much more.

The Journey

The Zohar is framed as the narrative of what scholar Nathan Wolski describes as a group of “wandering mystics headed by the grand master, Rabbi Shimon bar Yohai,” who converse with each other and interpret the Torah while traveling through the Holy Land. The act of traveling allows for freedom of imagination, and hence anywhere along the journey is considered the ideal place for expounding the deepest mysteries of Torah.

Language

As in previous works of Kabbalah, letters, numbers and words in the Zohar are considered to be powerful entities, indeed the very building blocks of Creation. The power of language includes both divine speech, that creates and continues to re-create the world each day, and human speech, which can influence both this world and the divine realm through prayer and contemplation.

Torah Commentary

Much of the Zohar takes the form of commentary and sermons, following the order of the books of the Torah. However, unlike traditional midrash, the Zohar purports to reveal the secret, inner meanings of the Torah. Biblical characters and stories are treated as symbols of states of the soul and aspects of the divine.

The 10 Sefirot

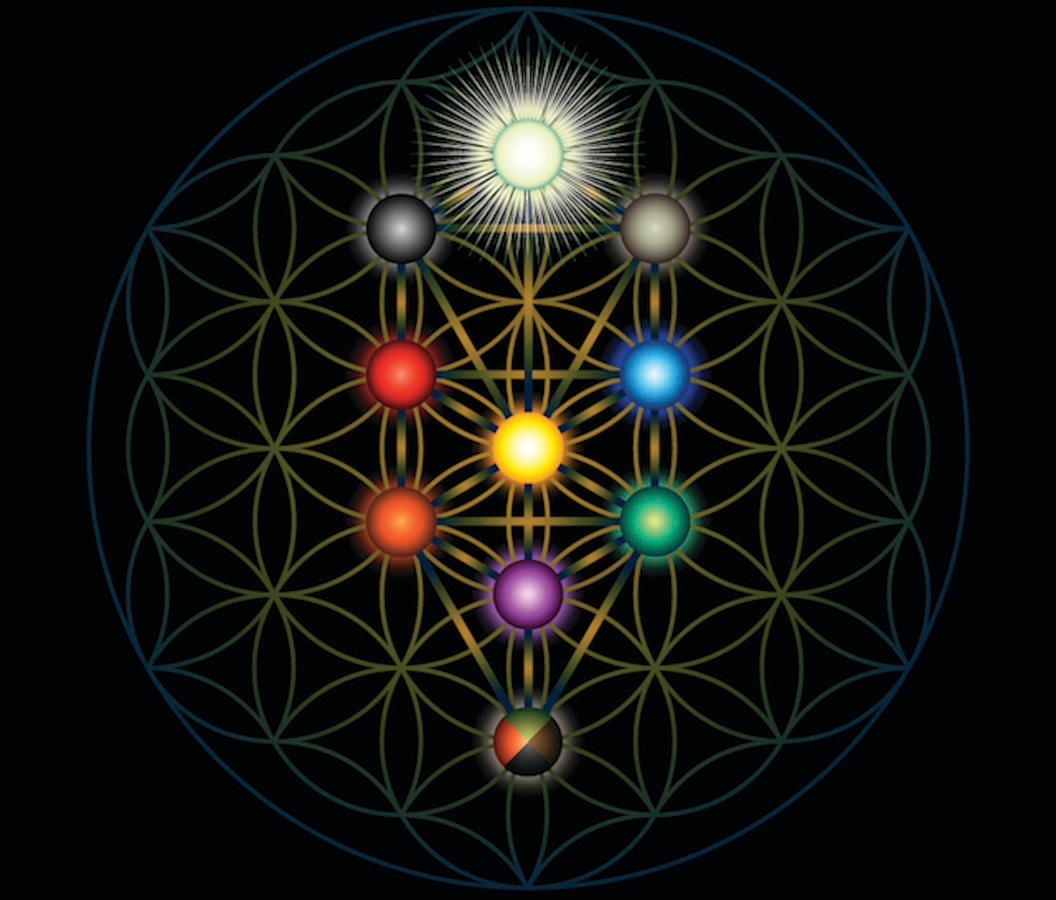

The nature of God (known as Ein Sof, the endless One) is one of the Zohar’s central concerns. The 10 sefirot, which first appear in pre-kabbalistic mystical texts, recur in the Zohar.The sefirot are expressions of God’s being; they are part of God and also represent the modes through which God relates to the world. These 10 aspects of God also serve as a template for human spiritual experience. The sefirot are:

- Keter (Crown)

- Hokhmah (Wisdom)

- Binah (Understanding)

- Hesed (Mercy)

- Din (Justice)

- Tiferet (Beauty)

- Nezah (Eternity)

- Hod (Glory)

- Yesod (Foundation)

- Shekhinah (the feminine aspect of God) or Malkhut (Royalty)

Sacred Study

The literary form of the Zohar lends itself to the quest for spiritual enlightenment through the act of text study. In the Zohar, the act of study is depicted as the highest mode of religious behavior, the way to achieve enlightenment and connection to God.

Mystical — and Erotic — Union with God

The goal of Kabbalah, and other mystical traditions, is to facilitate the spiritual union of the human being with God through contemplative practices. In the Zohar, the act of spiritual contemplation takes on an erotic character, in which mystics are often studying late at night, and the relationship between the mystic and God is described as that between two lovers. God is characterized as a lover or bride (the Shekhinah), and the goal of prayer, study, and meditation is depicted as a mystical union with God, in which the mystic loses himself in the divine being (a state known as devekut, attachment to God). The Zohar often employs the metaphor of sexual union and birth to describe the creative process that takes place both in the divine and human realms.

Impact of the Zohar

As the major work of kabbalistic literature, the Zohar has influenced Jews and non-Jews alike. It set the stage for a proliferation of subsequent kabbalistic texts, such as the 16th-century writings of Rabbi Isaac Luria. The Zohar also was embraced by certain Christian scholars who saw parallels in its cosmological system to aspects of Christian theology, such as the Holy Trinity. The development of Hasidism, which distilled kabbalistic ideas into psychological concepts that could be applied to religious life, was another way in which the Zohar’s influence was felt.

And today, with new translations and scholarship making the Zohar accessible to more and more readers, the text has found new life among spiritual seekers globally.

How to Study the Zohar

According to many traditional teachings, one is supposed to wait until the age of 40 to study Kabbalah, in order to be psychologically and spiritually prepared for these texts. The dense, complicated and esoteric character of these texts make them ideal for advanced students of Jewish texts. The Zohar requires a strong foundational knowledge of Hebrew, Aramaic, Torah, Talmud and Midrash. Even though new translations have made the text more accessible, the complex vocabulary and imaginary landscape of the Zohar make it difficult to study without guidance from an experienced scholar.

Recommended Further Reading

A Journey into the Zohar: An Introduction to The Book of Radiance

Hasidic

Pronounced: khah-SID-ik, Origin: Hebrew, a stream within ultra-Orthodox Judaism that grew out of an 18th-century mystical revival movement.

Talmud

Pronounced: TALL-mud, Origin: Hebrew, the set of teachings and commentaries on the Torah that form the basis for Jewish law. Comprised of the Mishnah and the Gemara, it contains the opinions of thousands of rabbis from different periods in Jewish history.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.

Zohar

Pronounced: ZOE-har, Origin: Aramaic, a Torah commentary and foundational text of Jewish mysticism.