Sefer Yetzirah, or the Book of Creation, is an ancient Jewish mystical work that describes God’s process of creating the universe. It is a short book, written in Hebrew and composed of brief, cryptic, poetic passages that offer mythic images and directions for meditative practice.

While there are older Jewish mystical traditions, Sefer Yetzirah is the first book of what might be called proto-Kabbalah, the school of Jewish mysticism that emerged in the 13th century. Sefer Yetzirah has its own sacred structures and ways of understanding the world that differ in significant ways from the kabbalistic understanding, but many of its concepts significantly influenced later Jewish mystical tradition and practice.

Scholars debate when Sefer Yetzirah was written, proposing dates as early as the first century of the Common Era and as late as the 9th century, though recent scholarship suggests a date sometime in the 6th century CE. In Jewish legend, the book’s authorship is attributed to the patriarch Abraham, though many scholars now believe the book had multiple authors. Further, there are many manuscripts of Sefer Yetzirah with varying texts. There are three major versions: the Short Recension, the Long Recension, and the Saadyan Recension, named after the commentary written on it by Saadia Gaon. One theory is that the book was written in north Mesopotamia, though other locations (such as Israel or Egypt) are also possible.

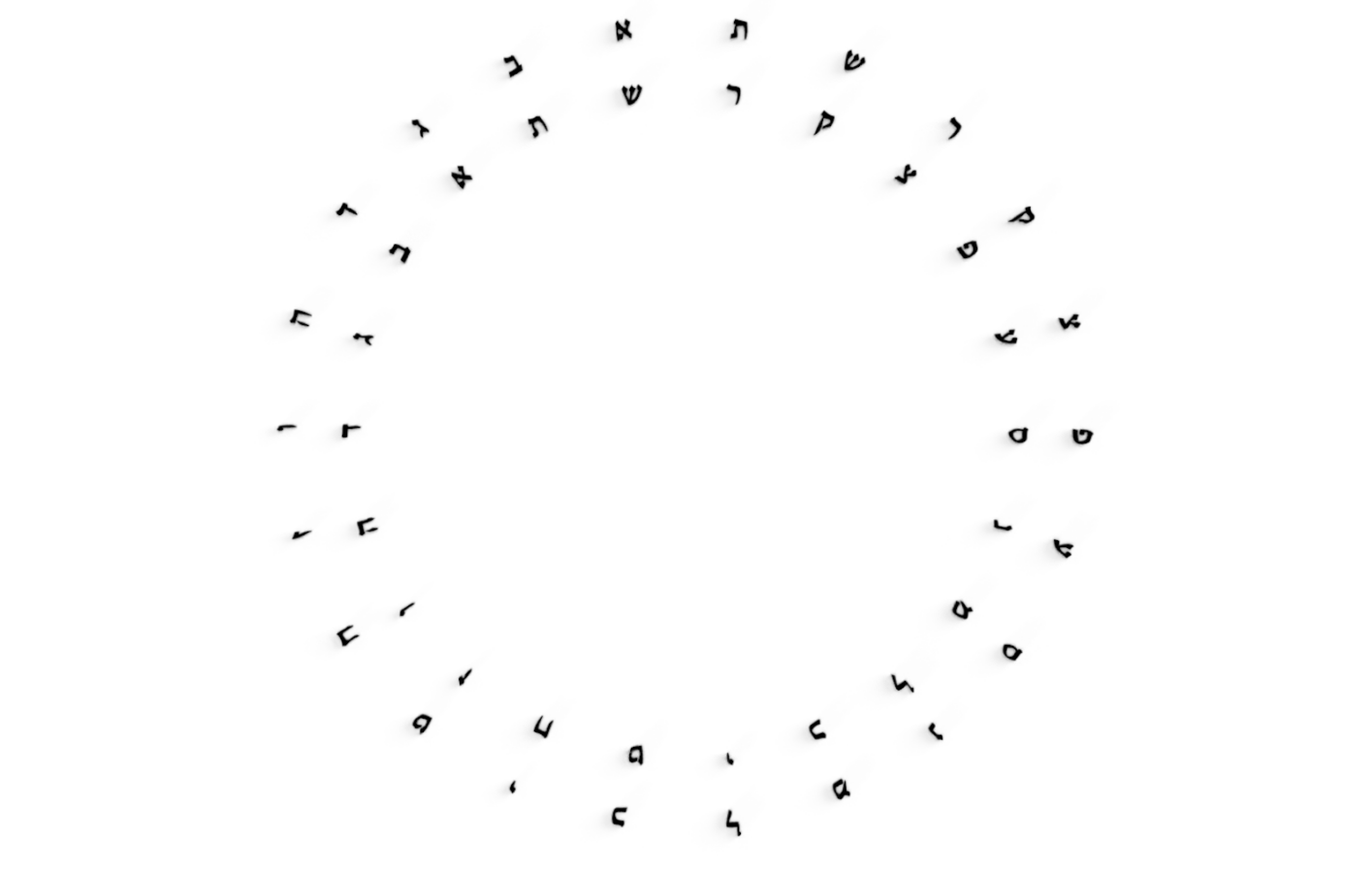

The book describes God’s process of creating the universe using “32 paths of wisdom” — essentially, channels through which God’s creative intention manifests in various aspects of creation. These paths include the 22 letters of the Hebrew alphabet, which God engraves into the fabric of existence, as if carving stone tablets. The remaining paths are the ten sefirot, better known in later mystical tradition as the ten emanations (or attributes) of God.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

In Sefer Yetzirah, sefirot appears to mean something like “dimension.” The ten sefirot are fundamental dimensions of the physical universe, a kind of frame within which the concrete aspects of creation can unfold. There are two lists of the sefirot in Sefer Yetzirah, and they differ somewhat — both from each other and those of later Kabbalah, which suggests the book’s diversity of authorship. We might call these two lists dimensional (dealing with the dimensions of the cosmos) and elemental (describing the fundamental substances of the cosmos).

In one rendering, they are beginning and end (the dimension of time), good and evil (the dimension of person), and north, south, east, west, up and down (the dimension of space). In the other rendering, the sefirot are divine breath, breath, water, fire, north, south, east, west, up and down. As the process of creation progresses, Sefer Yetzirah uses the sefirot to describe a kind of cosmic temple, a cube-like space that God creates and then carefully seals to create an ordered world. God resides within this sacred world-space, which then fills with the phenomena created by the letters and sefirot.

Unlike most paradigms of Jewish mysticism, Sefer Yetzirah directs the mystic to contemplate the physical universe rather than hidden worlds and is thus a more practical guidebook than the Zohar, the best-known work of Jewish mysticism. The book frequently addresses the spiritual practitioner directly, inviting the reader of the book to engage in meditation (particularly visualizing or pronouncing various permutations of letters, which is a practice of combining letters in sequence so as to produce meditative and/or magical effects) and discipline the consciousness in order to fully understand its concepts.

Professor Tzahi Weiss has suggested that Sefer Yetzirah is unusual for its time in its disinterest in law and Torah commentary and is thus not a rabbinic book — that is, the writing and concepts have little in common with the Judaism developed by the Talmud. There is relatively little quoting of verses, no legal discourse, and none of the back-and-forth conversation typical of rabbinic text. Rather, the book speaks in brief poems, often addresses the reader, and has a universalist flavor, focusing on the individual relationship with the Creator rather than the collective covenant between God and the Jewish people. The book’s response to the destruction of the Second Temple is to imagine a cosmic temple that can be found anywhere, via contemplation of the Hebrew letters, as opposed to the rabbinic response, which was to locate sanctity in the sacred text. Still, by using both the language of engraving letters and the language of temple building, Sefer Yetzirah connects sacred text (the letters) with the world (the cosmic Temple).

The book’s impact on the medieval texts of Kabbalah was considerable. The sefirot, the power of Hebrew letters, and the notion of an organic connection between the transcendent divine and the physical world — all these originate with Sefer Yetzirah and would come to permeate later kabbalistic works such as Sefer HaBahir and the Zohar. Another concept from Sefer Yetzirah is God’s partnership with an entity that meditates between physical and spiritual realms and is also a part of the divine. Sefer Yetzirah calls this entity “Wisdom” and later kabbalah uses the term shekhinah, among others. Kabbalistic commentaries have frequently focused on reconciling the kabbalistic picture of God and the cosmos with the somewhat different picture painted by Sefer Yetzirah.

Over time, there have been many questions about the genre and intention of the book. The medieval sage Saadia Gaon’s commentary treats Sefer Yetzirah like a book of philosophy, while the kabbalists treated it as a description of how to move divine realms. Some contemporary scholars understand the book to be connected to Jewish magical literature, citing the talmudic passage (Sanhedrin 67a) that mentions the sages using a book called “The Laws of Creation” to make a person via magic, or noting the parallels with Jewish magical artifacts like incantation bowls. Indeed, some believe the book can be used to create a golem, a human-made life-form. The book is so unusual in genre that it is hard to situate, but various scholars have suggested it may have been influenced by Gnosticism, Syrian Christianity, Sanskrit understandings of grammar, and more.

Sefer Yetzirah has not been much studied by contemporary Jews. This is perhaps due to its cryptic brevity and its differences from better-known Jewish genres from midrash to medieval Kabbalah. Yet the book offers a fresh look at Jewish mysticism in which the divine can be found not in transcendent or hidden realms, but on earth, in the physical qualities of the cosmos. Sefer Yetzirah’s meditative practices often feel postmodern, inviting the practitioner to become, like the engraved letters, a hollow channel for the forces of being. The book’s rich imagery and exploration of the mysteries of creation are a gift to contemporary Jews and beyond.