Beginning in the 10th century, Jewish mystics and philosophers wrote commentaries on Sefer Yetzirah, a book about the secrets of creation probably written around the third century. At the same time, Jewish mystics compiled works of heikhalot literature, an early corpus of texts focused on mystical ascents to heaven. These endeavors formed the bridge between early Jewish mysticism and its medieval golden era.

Two new mystical movements emerged in the 12th century. The Hasidei Ashkenaz (“the pious ones of Germany”) collected previously written mystical texts and wrote treatises on the supernatural, including astrology and demonology. For the most part, the Hasidei Ashkenaz were associated with a single family, the Kalonymus family.

Meanwhile, kabbalah, the medieval mystical tradition whose practitioners attempted to understand, affect, and communicate with the divine, was being developed in Provence and Northern Spain. Sefer ha-Bahir, a book of unknown authorship,is the most important early kabbalistic work. This book, written in the form of traditional midrashim—rabbinic dialogues and commentaries on the biblical text—introduces a revised theory of the sefirot, the ten attributes of God first mentioned in Sefer Yetzirah. In kabbalah, God as God—the Ein Sof or “the Infinite”—cannot be comprehended by humans. God can only be understood as He reveals himself in the sefirot. The sefirot are dynamic; they interact with each other and can be affected by humans. Indeed, much of the Kabbalah is an attempt to influence and “fix” the sefirot.

The doctrine of the sefirot reached its fullest articulation in the Zohar, a mystical commentary on the Torah. The Zohar interprets the Torah symbolically in an attempt to extract secrets about the divine realm. It is also structured like a midrash, is written in Aramaic, and was long attributed to the 2nd-century sage Shimon bar Yohai. The Zohar is now believed to be the work of the 13th-century Spanish Jewish mystic Moses de Leon, or as recent scholars have suggested, the work of a group of mystics including Moses de Leon.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

The kabbalah of the Zohar is a form of theosophic kabbalah, as it aims at initiating change within God. The kabbalah of Abraham Abulafia (1240-1291), on the other hand, is internally directed. It aims at affecting change within the mystic himself. Abulafia used chanting, meditation, and music to help him achieve this mystical experience. Like the theosophic kabbalists, Abulafia used the Torah to reach his mystical goals, but instead of interpreting the text of the Torah, he deconstructed its words and meditated on its letters. Abulafia aimed at achieving nothing less than prophecy, and he believed that this could be attained by taking apart Hebrew words and reorganizing them as divine names.

After the expulsion of Jews from Spain in 1492, the center of Jewish mysticism moved to the Palestinian city of Safed. There, Moses Cordevero (1522-1570) wrote a definitive commentary on the Zohar, and other important mystics, like the great halakhist Joseph Caro (1488-1575), taught and wrote. Isaac Luria (1534-1572) was the greatest of the Safed kabbalists. His most important theological innovation was his theory of creation. According to Luria, the creation of the world was a complicated, delicate activity that required a transformation of the divine being. Before the world was created, God occupied every inch of the universe. In order to make room for a world, God needed to contract, a process Luria called tzimtzum. After this contraction, God directed divine light into vessels, but the vessels couldn’t contain the light, and they broke, letting evil and imperfection into the world. The purpose of human history is tikkun, fixing the broken vessels. This is achieved by fulfilling the commandments of the Torah.

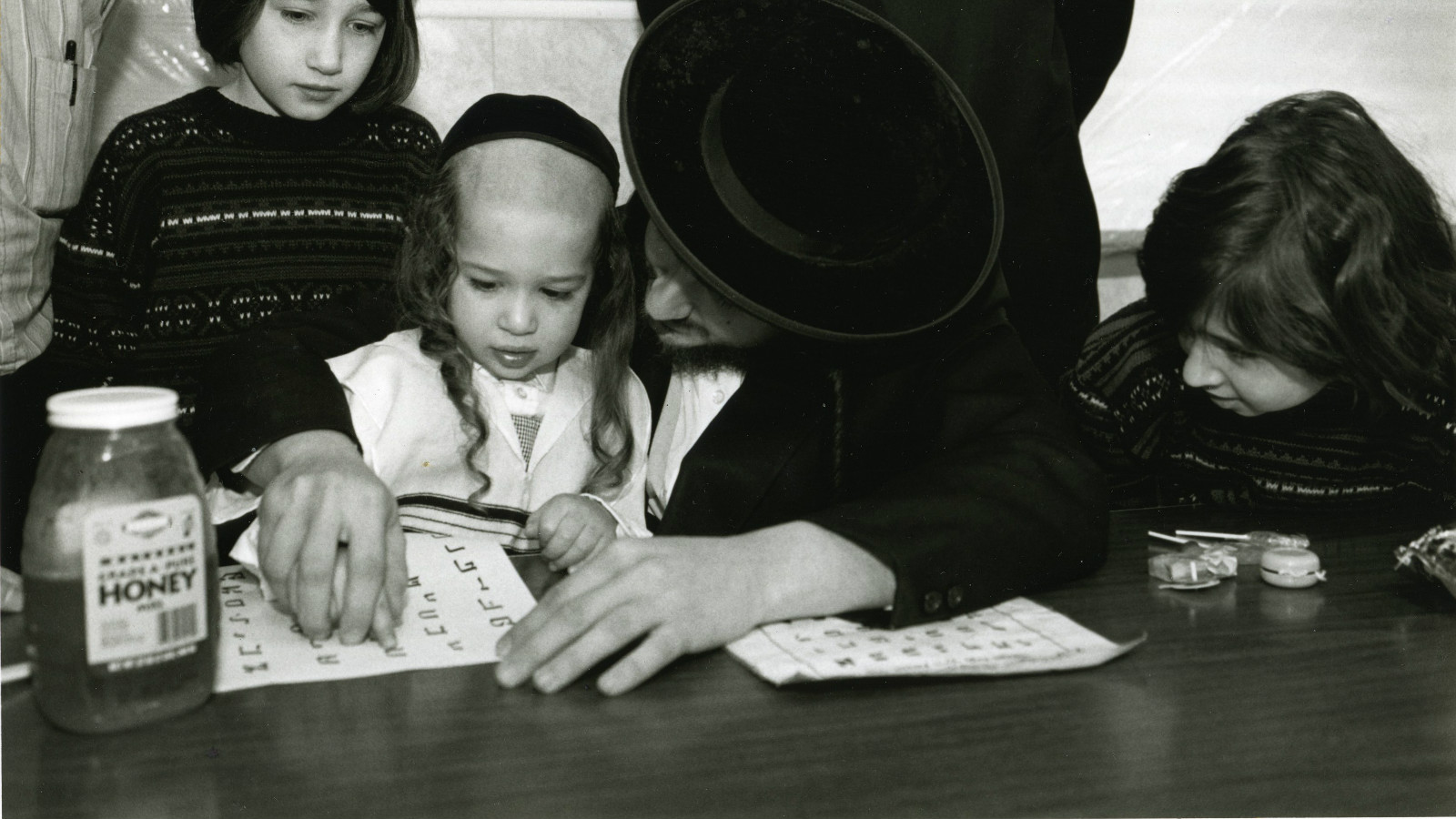

Hasidism emerged in the middle of the 18th century. The movement is traced to Israel ben Eliezer, known as the Baal Shem Tov (1700-1760)—usually translated as “Master of the Good Name”—an itinerant teacher and healer who taught that everyone, even the uneducated masses, can have personal interaction with the divine. The ultimate value of Hasidism is devekut, attachment to God.

Dov Baer, the Maggid (Preacher) of Mezeritch, succeeded the Baal Shem Tov as the leader of Hasidism. Eventually, however, Hasidism divided into several branches, often named for the geographic location where they took root. Each Hasidic sect has a leader, known as a rebbe or tzaddik, who serves as something of a facilitator, enabling the relationship between his constituents and God. The role of the rebbe often passes from father to son.

Initially, Hasidism was fiercely opposed by traditional Jewish authorities. Ironically, many Jews now perceive Hasidim (as members of the various Hasidic sects are known) as embodying the most traditional form of Judaism.

Hasidic

Pronounced: khah-SID-ik, Origin: Hebrew, a stream within ultra-Orthodox Judaism that grew out of an 18th-century mystical revival movement.

Kabbalah

Pronounced: kah-bah-LAH, sometimes kuh-BAHL-uh, Origin: Hebrew, Jewish mysticism.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.