Although celebrated as heroes who saved Jewish practice and Torah law from suppression and abrogation by the Syrian Greeks, the Maccabees are portrayed in the First Book of Maccabees as religious zealots, murdering coreligionists who had chosen the path of Hellenism.

The historical reality is murky, refracted as it is through the political and religious agendas of First and Second Maccabees (books relating the Hanukkah story that the rabbis chose not to include in the Hebrew Bible). Because of this ambiguity, both interpretations have some legitimacy, and later commentators choose the one most consonant with their own needs and goals.

For example, readers who have personally experienced anti-Semitism may identify Mattathias as a hero who was loyal to his religious identity in the face of an anti-Semitic Greek civilization. On the other hand, civil libertarians may judge the Maccabees less generously, criticizing their infringement on the civil rights of their coreligionists [the latter of whom may also have treated those belonging to the Maccabean party in a similar manner].

The Role of Hellenism

Central to any assessment of the Maccabees is an evaluation of the role of Hellenism, an ideology whose universalistic outlook was based on Greek ideas and athletic prowess. Following in the footsteps of Alexander the Great, Hellenism became a political tool used by the Syrian Greeks to consolidate their power among the wealthy bourgeoisie. In turn, the aristocratic elites who embraced Hellenism gained access to the social and economic perquisites flowing to citizens of a Greek polis, including the right to mint coins, to take part in international Hellenistic events, and to receive protection from the city’s founding ruler.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

But Hellenism encompassed more than a pragmatic relationship between the ruler and local economic elites; it also represented an “enlightened” worldview considered by many to be the way of the future. Nations who shut themselves off and did not confront the challenge of Hellenism were falling by the wayside. Because it was viewed as the wave of the future, the pressure to acculturate to Hellenism was quite intense in Judea. Therefore, the people of Judea had to decide whether the universalistic focus of Hellenism constituted a danger to their ancestral religion and its God or whether it simply represented a more modern and “progressive” way of life that could be merged with Jewish practice.

Reform or Revolt?

Was the appropriate response, then, to reform Judaism in the spirit of Hellenism or to assume a stance protective of traditional Jewish values by “liberating” Judea from the Syrian Greeks? The Jewish Hellenists chose the first path; they wanted to move beyond separatism and assimilate the positive aspects of Greek culture into Judaism. As First Maccabees recounts, “In those days there emerged in Israel lawless men [Jewish Hellenists] who persuaded many, saying, ‘Let us go and make a covenant with the nations that are around us; for since we separated ourselves from them, many evils have come upon us’” (I Maccabees 1:11).

Jewish Hellenists used the secular power structures for their own benefit. First Jason and then Menelaus were able to secure the position of High Priest from Antiochus IV Epiphanes by way of monetary bribes and other machinations. Yet the involvement of these wealthy Jewish aristocrats and priests in Hellenism complicates any assessment of the role of the Maccabees. Whereas a liberator is generally one who frees a country from domination by a foreign power, the Maccabees seem to have “liberated” the loyal Jewish masses from the Hellenist Jews and their Syrian Greek allies in the context of a civil war. An assessment of the legitimacy of the Maccabean liberation, therefore, depends on whether the Hellenists are viewed as apostates or as Jews who have taken on some Greek ways.

According to historian Elias Bickerman, Jason and Menelaus wanted to preserve aspects of Judaism that fit with Greek ideals, like a universal God, but to remove those parts of Jewish practice that separated Jews from others: dietary laws, Sabbath observance, circumcision. Some Hellenists continued to worship the Jewish God, but moved their worship to outdoor sanctuaries and sanctioned the pig as a sacrificial animal. It is interesting, however, that even in Second Maccabees, which is considered an anti-Hellenist tract, envoys representing Jerusalem at the quinquennial games in Tyre [the ancient version of the Olympics] “thought it improper” to purchase a sacrifice for Hercules. Instead they decided to fit out a ship and donate it to Tyre (II Maccabees 4:18-20). Although these Hellenists were willing to participate in the athletic contests, they appear to have been squeamish about doing something completely counter to Torah law.

When evaluating the Maccabees’ role, one must ask whether these Hellenist Jews, deemed apostates by the Maccabees and their supporters, had the right to assimilate their Jewish observance to the surrounding Greek culture. The Maccabees answered with a resounding “no,” and their judgment was confirmed when eventually Menelaus convinced Antiochus to enact a decree prohibiting Mosaic law. Through Antiochus’ decree, observance of the commandments of the Torah became a capital offense, and the worship of pagan gods was required.

The Maccabean struggle was also driven by issues of social class. Because only the wealthy — the urban ruling class and large landowners, led by the priests — were citizens, the “democracy” of the Hellenized Jerusalem polis oppressed the vast majority of Jews, who were powerless. Even before the Antiochan persecutions, social antagonisms existed between the zealots of the traditional faith — the urban craftspeople and village dwellers — and the free-thinking Hellenizers, suggesting that the Maccabees may have been liberators, but that they were also driven by some degree of self-interest.

Legitimization Through Zealotry

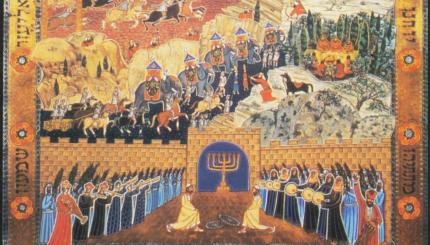

Whereas some modern sensibilities will be offended by the Maccabees’ vicious treatment of the Hellenist Jews, First Maccabees not only lauds Mattathias’ zealotry against his coreligionists, but uses that very zealotry to legitimize the Maccabean dynasty. In First Maccabees, Mattathias acts in the tradition of other zealots in the Torah by murdering a fellow Jew in Modi’in who approaches a pagan altar to offer a sacrifice when requested to do so by a royal official. When this apostate Jew steps up to the altar, Mattathias kills him as well as the government official and then tears down the altar. Mattathias declares, “Let everybody who is zealous for the law and stands by the covenant follow me” (I Maccabees 2:27). With this self-conscious echoing of the words of Moses when confronted with the Golden Calf – “Whoever is for the Lord, come here” (Exodus 32:26) – First Maccabees begins its justification of Maccabean zealotry.

First Maccabees continues by explicitly comparing Mattathias to the biblical figure Pinchas, who killed a tribal leader and his Midianite partner to stop the spread of idolatry and was rewarded by God with a “brit shalom” — covenant of peace — of eternal priesthood (Numbers 25). The implication is that Mattathias derives his political and religious authority from this very act of zealotry, this taking of the law into his own hands, based on his perception that the continued existence of the Jewish community was in danger.

Although Mattathias saw himself as acting in a situation of conflict between an earthly power and the law of God, his act might be viewed from the outside as one of political terrorism; he had committed murder for the sake of what he perceived to be a greater good. Judah continued the fight begun by Mattathias by actively attacking apostasy — destroying idolatrous altars, compelling observance of Torah by force, circumcising newborn infants, and killing apostate violators of Torah law.

Later in the story, the Maccabean self-interest also led them to reinterpret Torah law so that the Jews hiding with them in the wilderness could defend themselves from government attack on the Sabbath. By interpreting the law on their own authority, the Maccabees were setting themselves up as an opposition government, infringing on the prerogatives of the sitting High Priest.

Although the text of Maccabees views Judah as a liberator whose zealotry was necessary to preserve the Torah and the Jewish people, later rabbinic commentators frowned upon such zealotry, realizing the danger of individuals taking the law into their own hands and interpreting it in accord with their own interests. Consequently, normative Jewish law limits “legitimate” zealotry nearly to the point of nonexistence: A zealot is not allowed to act preemptively in expectation of a desecration, nor punitively after the desecration has been completed; if he does so, he is treated as a murderer. Because a zealot is considered to be acting outside the law, the desecrator has the right to kill a zealot in self-defense. In addition, rabbinical courts were forbidden to give permission to zealots to act or to teach zealotry.

In the end, the Maccabees must be judged to be both liberators and zealots. Like many figures in the Bible, these apocryphal heroes are multi-layered, and their meaning is unraveled by successive generations based on their own needs and experiences. In the world today, we may identify with the Maccabean fight to preserve Judaism in the face of assimilation and anti-Semitism, while at the same time working to mitigate religious zealotry that threatens to turn Jew against Jew.

Explore Hanukkah’s history, global traditions, food and more with My Jewish Learning’s “All About Hanukkah” email series. Sign up to take a journey through Hanukkah and go deeper into the Festival of Lights.

Hanukkah

Pronounced: KHAH-nuh-kah, also ha-new-KAH, an eight-day festival commemorating the Maccabees' victory over the Greeks and subsequent rededication of the temple. Falls in the Hebrew month of Kislev, which usually corresponds with December.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.