The First and Second Books of Maccabees contain the most detailed accounts of the battles of Judah Maccabee and his brothers for the liberation of Judea from foreign domination. These books include within them the earliest references to the story of Hanukkah and the rededication of the Temple, in addition to the famous story of the mother and her seven sons. And yet, these two books are missing from the Hebrew Bible.

In order to begin addressing the question of this omission, it is important to understand the formation of the Hebrew biblical canon. The word “canon” originally comes from the Greek and means “standard” or “measurement.” When referring to a scriptural canon, the word is used to designate a collection of writings that are considered authoritative within a specific religious group. To the Jewish people, the biblical canon consists of the books found in the Tanach (Hebrew Bible).

The canonization process of the Hebrew Bible is often associated with the Council of Jamnia (Hebrew: Yavneh), around the year 90 C.E. Rabbi Yochanan ben Zakkai managed to escape Jerusalem before its destruction and received permission to rebuild a Jewish base in Jamnia. It was there that the contents of the canon of the Hebrew Bible may have been discussed and formally accepted. However, this is a scholarly proposition that has lost adherents in recent years. Be that as it may, some of the debates surrounding these discussions–whenever and wherever they may have taken place–do appear in rabbinic literature, although we have no complete surviving record of these debates. Therefore, we can only speculate on why some materials were excluded from our canon and others included.

Several Theories

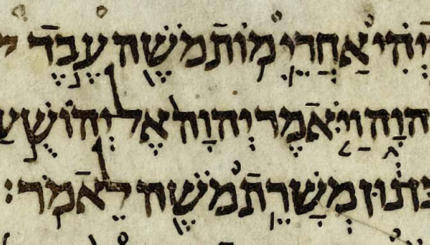

There are various theories to explain the exclusion of the apocryphal books. One theory is that only books written originally in Hebrew were considered for inclusion in the canon. However, the Book of Daniel, although included within the canon, is to a large extent written in Aramaic. Even more problematic is the fact that scholars believe that the First Book of Maccabees was indeed written originally in Hebrew, therefore meeting the language criterion for inclusion–and yet it is absent from the biblical canon.

Another theory to explain the omission of the first two Books of Maccabees is based on the dating of these documents. Although it is often assumed that the biblical canon was formalized at Jamnia, there is some speculation that the accepted list of books was in existence long before. In other words, perhaps the gathering of rabbis at Jamnia inherited a list of documents already unofficially recognized as canonical and simply formalized this list.

If this is true, the relatively late date of the Maccabean revolt would preclude its inclusion in an already accepted previous list. It would be too “new” a book for serious consideration, since it had no history grounding it securely within tradition. This theory, however, is severely weakened through a comparison with the Book of Daniel, since Daniel is included within the biblical canon in spite of the fact that most scholars date the latter book to the time of the Maccabean revolt around 165 B.C.E.–in other words, to the time of the story related in the Books of Maccabees.

It has also been suggested that the exclusion of the Books of the Maccabees can be traced to the political rivalry that existed during the late Second Temple Period between the Sadducees and the Pharisees. The Sadducees, a priestly class in charge of the Temple, openly rejected the oral interpretations that the Pharisees, the proto-rabbinic class, openly promoted. The Maccabees were a priestly family, while the rabbis who may have determined the final form of the biblical canon at Jamnia were descended from the Pharisees. Is it possible that the exclusion of the Books of Maccabees was one of the last salvos in the battle between the Pharisees and Sadducees? Would the rabbis at Jamnia have been inclined to canonize a document that so clearly praised the priestly Hasmonean family?

Pragmatism and Politics

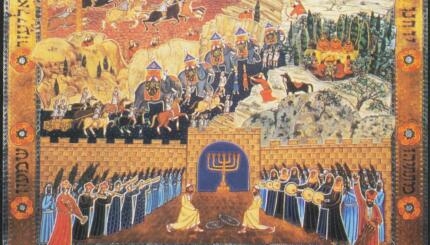

Perhaps the answer lies more within the realm of pragmatism and politics. The Books of Maccabees describe the revolt led by the Maccabean family against the Syrian king, Antiochus Epiphanes. A couple of centuries later, Jewish scholars found themselves in Jamnia with the Temple destroyed and Jerusalem lost. Their circumstances were the result of their own failed revolt against the Romans.

Perhaps they felt it unwise to promote a text that heralded the successful outcome of a Jewish revolt. It may have posed a threat both internally and externally. The Romans would certainly not look kindly upon the popularization of such a text, since it might very well reintroduce the concept of revolt to a population desperately trying to survive the devastating outcome of its own failed attempts. Ironically, this very internal/external struggle lies at the core of the Hanukkah story, and perhaps it was this very struggle playing out again in history that prevented the basic texts about Hanukkah from being included within the biblical canon.

Although the Books of Maccabees were not included within the Hebrew Bible, they are still of value. Yet even this is difficult within a traditional Jewish context, due to another historical layer. First and Second Maccabees were included in the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible originally prepared for the Jewish community of Alexandria. However, the Septuagint became the official version of the Bible for the nascent Christian Church. When this happened, its authoritative nature was rejected by the Jewish community. Ironically, the Books of Maccabees survived because they became part of the Christian canon, for otherwise they most certainly would have been lost during the centuries. But once this Christian canonization occurred, these books became lost to the Jewish world for many centuries.

Today there is a renewed interest in these books within the Jewish community. Students of Jewish history and Jewish literature recognize the value of these documents that took such pains to record details, events and personalities of a major period in Jewish history. While not considered as part of the canon in any Jewish community, the books are again being read and studied to help enrich our understanding and our celebration of Hanukkah.

Explore Hanukkah’s history, global traditions, food and more with My Jewish Learning’s “All About Hanukkah” email series. Sign up to take a journey through Hanukkah and go deeper into the Festival of Lights.

Hanukkah

Pronounced: KHAH-nuh-kah, also ha-new-KAH, an eight-day festival commemorating the Maccabees’ victory over the Greeks and subsequent rededication of the temple. Falls in the Hebrew month of Kislev, which usually corresponds with December.

Midrash

Pronounced: MIDD-rash, Origin: Hebrew, the process of interpretation by which the rabbis filled in “gaps” found in the Torah.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.

Tanach

Pronounced: tah-NAKH, Origin: Hebrew, Hebrew Bible (an acronym for Torah, Nevi’im and Ketuvim, or the Torah, Prophets and Writings).