After the sack of Rome by the Visigoths in 410, Augustine of Hippo (354-430) composed The City of God, a philosophical treatise that would become a keystone of medieval Christian thought and inform European attitudes toward Jews and Judaism for the next 1,000 years.

Augustine’s position toward Jews was ambivalent, crystalizing a duality of fear and fascination that runs throughout the Western Christian tradition. Augustine claimed Jews were murderers of Jesus, for which they were forever doomed to exile and subordination. At the same time, he believed Jews should be protected from grievous harm, since wherever they lived they carried the Old Testament, which testified to Jesus’s fulfillment as the messiah and to Jewish blindness and rejection. This ensured Jewish survival, but at the cost of subjugation.

Augustine is a good place to start in order to understand the roots of European anti-Semitism in early Christianity and medieval Christendom. For it was the writers of the New Testament, buttressed by church fathers like Augustine, who developed a coherent theology based on those writings and laid the seeds for centuries of Judeophobia.

Augustine and the other church fathers were influenced by an earlier Greco-Roman legacy that both scorned and praised Jews. Many ancient thinkers were impressed by the biblical tradition and touted Jews for upholding the cardinal virtues of wisdom, courage, temperance, and justice. But Jewish difference aroused scorn. Some, like the historian Tacitus, found monotheistic beliefs and rituals bizarre or uncivilized. The most serious accusation was that Jews were misanthropes, hating all but their own group.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

But it was the expanding divide between the followers of Jesus and the Jews that fundamentally shaped the fate of anti-Jewish contempt, a conflict inscribed in the sacred texts of Christianity. The Gospels tell the story of Jesus of Nazareth, martyred as “King of the Jews,” whose original disciples were all Jewish but who Jews rejected as the messiah.

Five enduring images in the New Testament would profoundly shape perceptions of Jews in the Christian West.

First was the depiction of Judas, the traitor willing to sell out God for 30 pieces of silver. Second, was the portrait of Caiaphas and other Jewish leaders who were concerned only with their own power. Third, was the claim that Jews were “Christ-killers,” derived from the scene in the Passion narrative where the Jews call upon the Roman governor Pontius Pilate to crucify Jesus, assuming perpetual responsibility when they insist “his blood be upon us and upon our children.” Fourth, was the association of Jews with Satan, which was reinforced in the Gospel of John, when Jesus says to a group of Pharisees, “You are of your father the devil, and your will is to do your father’s desires.” Lastly, is the supersessionist claim — the doctrine that the new covenant through Jesus supersedes the old covenant with the Jewish people — which crowned Jesus’ followers as the new Israel, bestowing upon them the promises given by God to the Jews and projecting onto the forsaken Jews the curses of those accursed by the divine.

As the theology of Christianity developed from the second to the sixth century, these images would be amplified in sermons, repeated in the liturgy, rehearsed in passion plays, imbibed through folktales, and institutionalized as church law. Later, they would literally be carved into the stone and glass of cathedrals. Across Europe today one can still find the image of the synagogue depicted as an old, downcast, blindfolded, and broken widow opposed to the farsighted, upright church, a condensed supersessionist narrative for the illiterate masses.

From the sixth through the 11th centuries, church leaders sometimes railed against good relations with Jews, which suggests that such intimacy existed. Anti-Jewish legislation oscillated between protection and enforced subordination and it varied with individual leaders who usually followed the law of utility, doing whatever was good for them. Most importantly, anti-Judaism was not economic and populist. Indeed, Jews were the only heretical group allowed to practice a separate creed, and social and economic relations were relatively amicable.

A key turning point was Pope Urban II’s call for a crusade to liberate Christian holy sites from Muslims in 1095. The march of the Crusaders in the summer of 1096 marked the first mass slaughter and pillaging of Jewish “infidels” living in Christian territories, especially in the Rhine Valley, whose Jewish communities were the most numerous in Europe. In accordance with Augustinian doctrine, some counts and bishops sought to aid Jews until they were forced to yield before the zealous mob. Waves of new crusades over the next 200 years would follow with disastrous consequences.

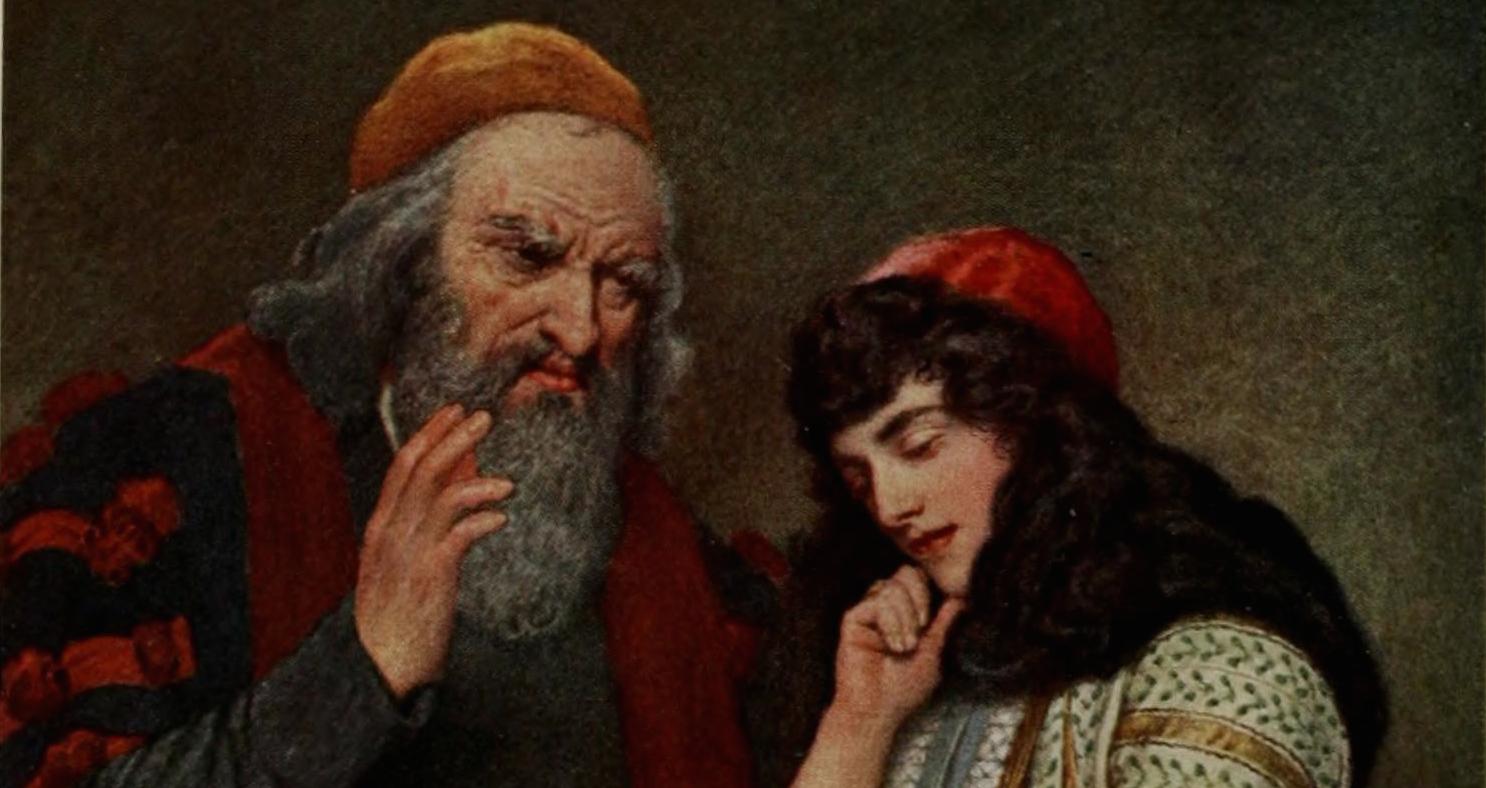

In their wake, new accusations against Jews emerged, most notably the blood libel, the accusation that Jews ritually murdered Christian children to use their blood for baking Passover matzah. New directives also followed: the mandate for a distinctive sign to be worn by Jews and Muslims to distinguish them from Christians, and the public condemnation of the Talmud in a series of mandated public disputations, beginning in Paris in 1240. The Fourth Lateran Council (1215) denounced Jews as “usurers” for lending money at interest, updating the archetype of Judas and alleging that Jews were avaricious and cheated Christians wherever they could. This stereotype was most famously dramatized by Shylock in Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice.

The systemic persecution of Jews worsened in the 14th century, which was cataclysmic for all Europeans. The great famine of 1315-1317 was followed by the bubonic plague, which killed more than one-third of all Europeans. Associations of Jews with witchery, dark sorcery, and the Antichrist fed rumors that the Black Death was the result of a plot by Jews to destroy Christendom, carried out by poisoning wells and springs. This was the origin of conspiracy theories that charged Jews with acting as a cabal to destroy the Christian world. Looting and carnage in hundreds of Jewish communities resulted, often followed by expulsions.

The most consequential of these would take place in Spain, where Jews had thrived for centuries, excelling in both intellectual and commercial pursuits and even serving as counsellors and physicians to the kings of Castile and Aragon. Following a brutal civil war from 1355-1366, a set of charismatic preachers fomented anti-Jewish violence, forcibly converting tens of thousands and massacring those who refused. Following conversion, all the barriers to social access were removed.

In 1449, to reset limits on those with Jewish origins who were then integrating into all sectors of Spanish society, “blood purity” laws were passed barring the entry of “New Christians” to public office and certain guilds, military and religious orders, as well as some towns. Still, some converts practiced Jewish rites in secret. To root out heresy, the Inquisition was formally established in 1478. Those suspected of being crypto-Jews or marranos were tortured or brought to public trial, and sometimes burned at the stake in festivals known as auto-da-fé (act of faith). In 1492, the remaining 160,000 Jews were expelled from Spain.

The discovery and conquest of the new world by Columbus that year, paid for in part by the confiscated millions taken from banished Jews, was the dawn of the modern world. As the transatlantic slave system developed in the Americas, the concept of races, previously applied only to describe animal breeding and blue-blooded nobility, merged with ideas of indelible blood purity from the Inquisition and were used to differentiate and hierarchize group character.

Systems of racial classification were fully birthed during the 18th century Enlightenment as Europeans sought to describe, classify, order, and label the world. Racial systems legitimated slavery and colonial domination as natural at precisely the moment when Europeans were rethinking their own social order. Simultaneously, Enlightenment values of scientific reason, constitutional government, and tolerance warranted emancipating Jews from medieval structures.

However, like the Augustinian ambivalence of old, Enlightenment ideas were also responsible for codifying new racial hierarchies that secularized the dichotomies of Christendom, especially when they were mixed with paeans to the people as the masses became involved in politics. Enlightenment values like liberty, equality, and fraternity were the backdrop to the revolution in France, where Jews were first given equal civil rights. Yet as industrialization propelled Europe to global hegemony in the 19th century, racism became a central axis of European identity. European nations and peoples defined themselves externally against colonized others and against Jews internally.

By the late 19th century, nation, culture, and race had become interchangeable terms. Jews and Judaism were also habitually depicted as the opposite of the highest values of the nation. A racialized, politicized, and programmatic anti-Semitism emerged as a force in western and central Europe based on the Aryan myth, which depicted Semites as a subversive group bent on ascendency. Exemplifying these trends, the Dreyfus Affair (1894-1906) ripped France apart over whether Captain Alfred Dreyfus, the only Jewish member of the military’s general staff, was a traitor selling military secrets to the Germans, or whether he was framed, as was proven the case.

For those left behind by the age of revolutions, Jews like Dreyfus who had risen to such lofty heights represented, in Richard Wagner’s phrase, the “plastic demon of modernity,” the embodiment of all that was threatening in this brave new world. The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a forgery by the Russian secret police during the Dreyfus Affair and purporting to capture the plan for Jewish world domination, would become the blueprint for modern conspiracy theories. After the massive dislocation and death in World War I and the Russian Revolution, it went viral.

Across postwar Europe, Jews were identified with those aspects of cultural degeneration and national corruption that fascists promised to eliminate. This would reach its crescendo in the Holocaust, where the horrors of total war transformed calls for racial hygiene into a distinctive siren song to cleanse and restore Germany, and ultimately all of Europe, by finally eliminating the Jew.