Esther — the heroine of the Purim story — was a Jewish woman who became queen of the Persian Empire. Her story represents the possibility of being both deeply Persian and deeply Jewish, and reminds me of my Jewish grandfather, Younes Dardashti, who rose to national fame in Iran in the 1960s as a singer beloved among Muslims. He became known as The Nightingale of Iran. As it turns out, Jews have played an integral role in Persian music for at least hundreds of years.

As many Persian Jews will tell you, their community has deep roots in the region reaching all the way back to 586 BCE — following the destruction of the first Temple. The critical importance of Jews to Persian music culture began, however, when Muslims conquered Persia in the 7th century CE. Because Islam has prohibitions against music-making, it was the Jews, Zoroastrians and Christians who maintained local musical traditions. This was particularly true during the 16th century Safavid Dynasty, when Shia Islam became the state religion and extremist religious policies labeled Jews as najis, or “impure.” Music — a marginalized profession among Muslim Persians — was one of the few trades Jews could legally pursue. The role of Persian Jews as the bearers of Persian music culture continued for hundreds of years.

Under the reign of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi from the 1940s through the 1970s, restrictions against Jews were lifted, and most consider this a “Golden Age” for Jews in Iran. Islamic music prohibitions and the stigma surrounding music began to disappear. As Iran broadcasted its first Persian classical radio stars in the 1940s, a few Jewish master musicians — descended from generations of Jewish professional musician families — achieved widespread fame.

Master tar player and composer Morteza Neydavoud (a Jew) came from one such family and reached the highest level of musicianship and fame in Iran. After composing and recording multiple albums, he began performing on Iranian radio in 1940. His song Morgh-e Sahar (The Bird of Dawn) is one of the most iconic Iranian songs ever written; it took on new meaning after 1979 as a song of protest against the Islamic Revolution. Here is a recording of the late master Persian vocalist Mohammad-Reza Shajarian and his son Homayoun Shajarian singing Neydavoud’s Morgh-e Sahar.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

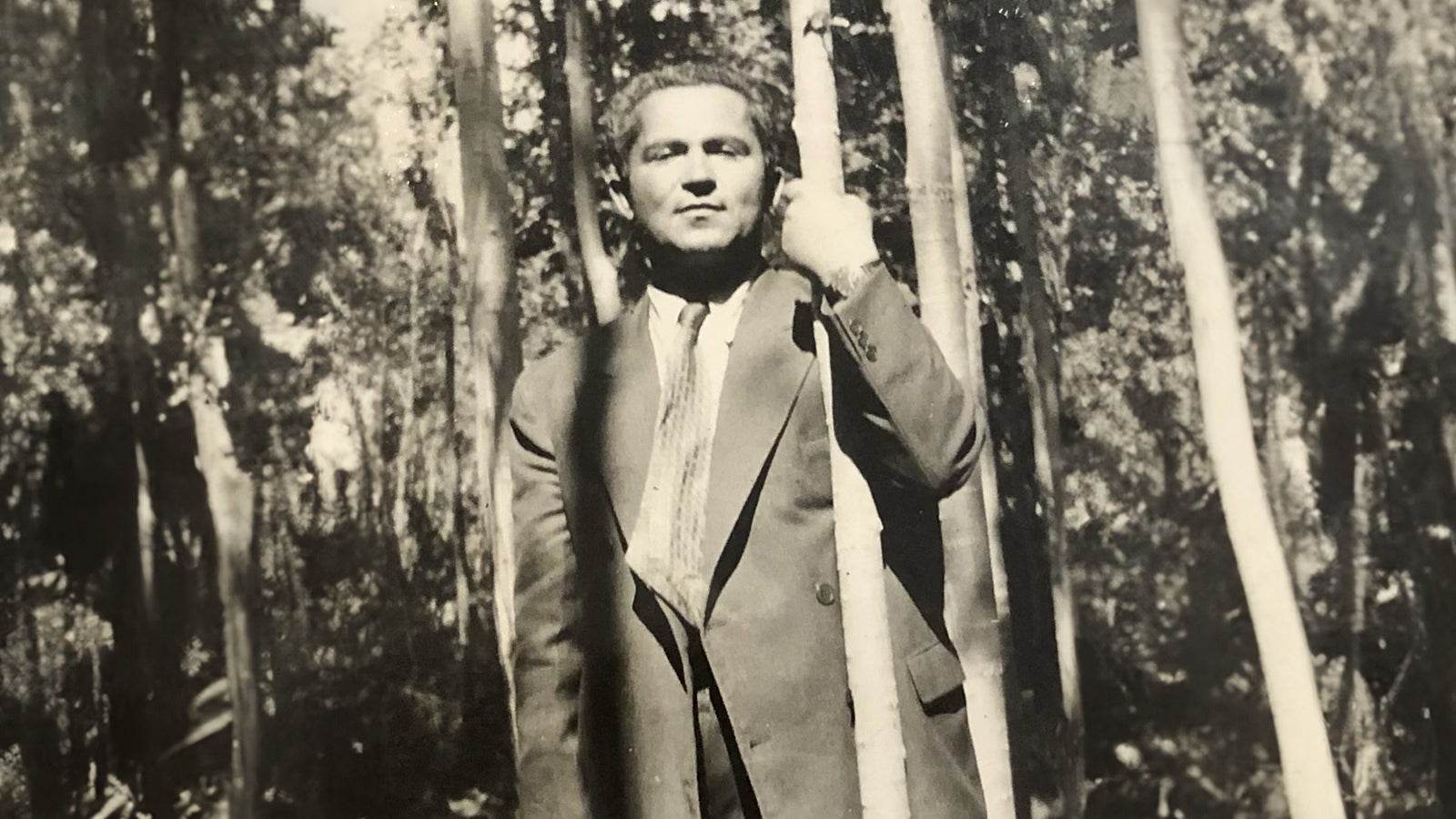

The other most renowned Jewish musician in Iranian history was my grandfather, Younes Dardashti. He did not hail from a family of professional musicians; instead, his break came when he was discovered dramatically at a party in Tehran, singing in the dark as a spontaneous response during a power outage. He became known as The Nightingale of Iran and is the subject of a 6-part audio documentary of the same name, which I created with my sister, Danielle Dardashti.

As we relate in the podcast, our Tehran-born grandfather, whom we call Saba (grandfather in Hebrew) was an Iranian radio star from the early 1950s to the mid-1960s and was beloved among Muslims. He is the only Jewish singer to have ever reached such stardom in Iranian society. In addition to radio, he sang at the most prestigious concert halls in Iran and at the Shah’s palace. Below is a recording of him singing on the radio in Persian. You can hear the vocal artistry that made him a celebrity beginning around 10:30 in the video:

Even when my grandfather was a celebrity on the radio, he would lead services as cantor at various synagogues in Tehran. In Iran, this was not a profession but rather simply an honor for a traditional Jew. Here is a 1970s recording from Tehran of him chanting the piece “Ish Elohim” (Man of God), a Hebrew piyyut, or sacred poetic song, sung in Persian communities around Lag B’Omer to memorialize Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai. It’s also sung at memorials for other members of the community.

When I lecture on Persian Jewish I point out that this Hebrew-language piece actually isn’t very different from the mainstream Persian art music that Muslims loved hearing my Saba sing. In his Hebrew chanting, my grandfather uses similar modes (including quarter tones) and techniques (like tahrir, Persian yodeling) as he utilizes in Persian art music.

Scholars have debated whether Jews were influenced by Persian music or Jews influenced Persian music. Whatever the direction of influence, and it may go both ways, the fact that Jews were the primary Persian musicians for hundreds of years made Jews almost synonymous with Persian music. It makes sense that Persian Jewish and non-Jewish Persian music have so much in common.

While we have many radio recordings of my Saba singing Persian art music in Iran, one of the few recordings of my grandfather singing Jewish music in Hebrew was of him chanting Selihot, penitential prayers chanted during the month of Elul before Rosh Hashanah. His renditions of these prayers are beautiful and moving. The last prayer he included in this recording of Selihot prayers is called Monajat, a Persian word that describes an intimate prayer with God. While we know of no others who sang it, my Saba always ended Selihot with Monajat, a Persian piece we believe he composed himself. It describes arising early to worship God and is similar in content to other mystical poems by Persian poets Rumi and Hafez that my Saba interpreted as a classical Persian singer. To my Saba, a devout Jew, innovating the Jewish Selihot ritual by incorporating his own Persian composition seemed totally natural. To me, the piece is a clear reflection of how he was seamlessly both Persian and Jewish. Since Jews in Tehran often led Selihot outdoors at community members’ homes in Tehran, there are many stories of nearby Muslims listening to my grandfather singing these Jewish prayers, admiring his beautiful chanting.

This past September, I released an album entitled Monajat, in which I duet with my Saba, sampling those old recordings of his chanting Selihot in Iran, like in the piece Adonai Hu Ha’elohim. That has been a very exciting and moving process for me. My Saba’s innovations with Jewish ritual gave me artistic license to reinvent my own version of Selihot in Monajat. Here it is on Spotify.

To me, one of the most meaningful parts of the project was emphasizing the shared musical culture of Muslims and Jews, particularly at a time when our communities are so divided. Though both history and the biblical story of Purim tell us that the experience of Jews in Persia was rarely untroubled, Queen Esther and my grandfather both gracefully demonstrate that being both Jewish and Persian is no contradiction.

In honor of Queen Esther, here are some other bold Persian Jewish women experimenting with Persian music that you can check out:

Israel:

Princess Laila: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T4npMwHQFTo

Moreen Nehedar: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aPOXnOHpxfI

Janet Yehudian: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tdrno6Va1d0

Los Angeles:

Chloe Pourmarody: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zcRhILAlbEo