Rabbi Eliezer said, “One who makes one’s prayers fixed, that person’s prayers are not sincere petitions” (Mishnah Berakhot 4:4)

READ: How to Choose a Siddur (Jewish Prayer Book)

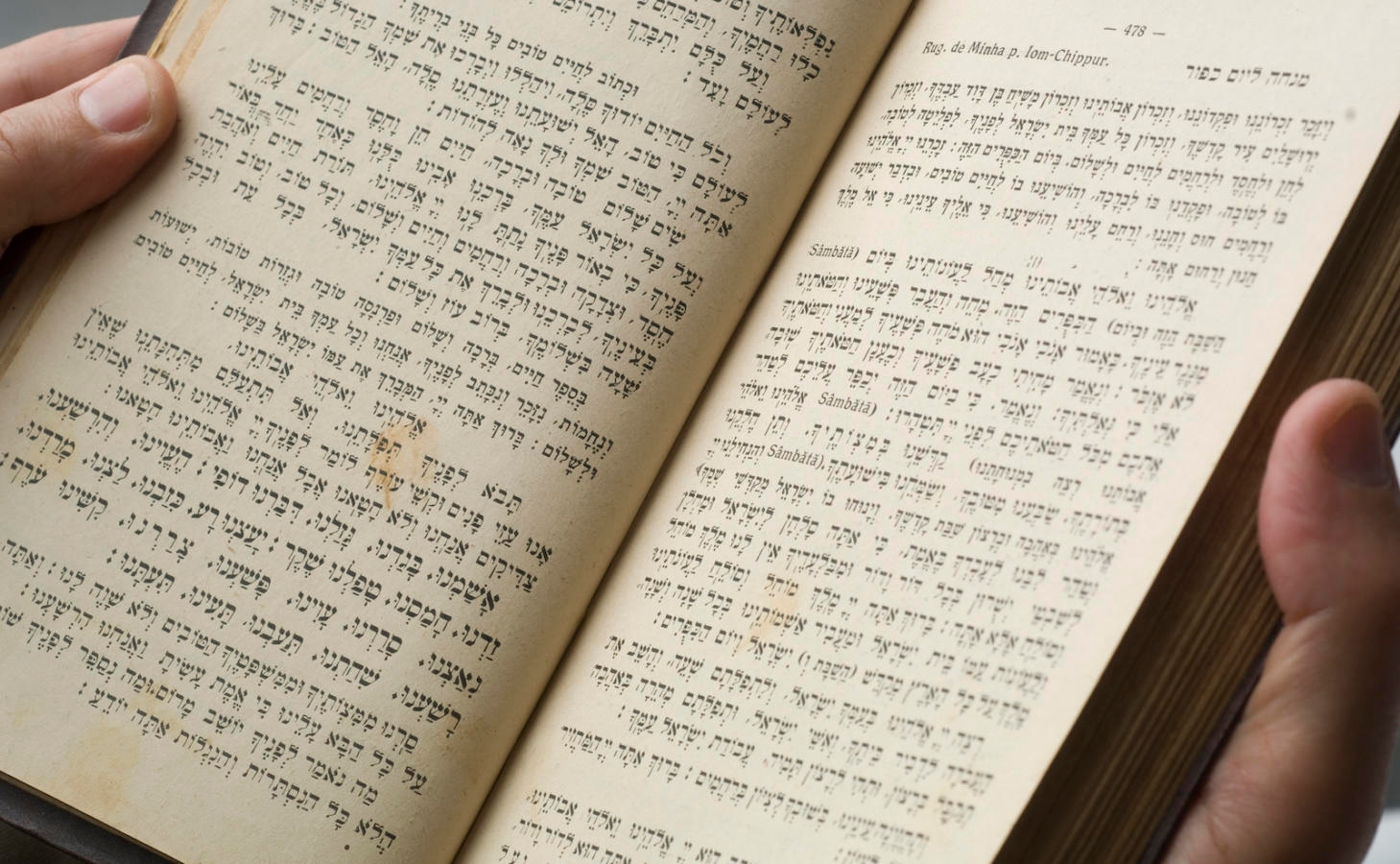

Heedless of Rabbi Eliezer’s comments, or perhaps chastened by the difficulty of regularly drafting new prayers, Jews created fixed texts and structures for prayer that were ultimately drawn together in the siddur, or Jewish prayer book. The word siddur means order and comes from the same root as seder, the special Passover meal. The particular order of Jewish worship was established largely during the first four or five centuries CE, although the components of that worship were drawn from earlier periods and have continued to develop until modern times.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Structure Dates to Talmudic Period

The structure for Jewish worship was developed during the Talmudic period. The morning service (Shachrit), which is the most complex of the three daily services, has two main foci:

1) The Shema, a selection of three paragraphs from the Bible (from Deuteronomy 6 and 11 and Numbers 15) affirming God’s unity and surrounded by thematically associated blessings before and after, and

2) The Amidah, a series of seven blessings (on the Sabbath) or 19 blessings (on weekdays) dealing with themes of repentance, sustenance, and the restoration of a messianic, Israelite kingship. Extra blessings are added when celebrating the beginning of a new month and other holidays.

Most of the other materials fit into structures that emulate these two central pieces; either they are passages from the Bible surrounded by blessings (like the Shema), or series of blessings (like the Amidah). In the first category is the Torah service, the verses of song (P’sukei d’Zimrah), and the Hallel (psalms recited on holidays). The second category includes the morning blessings. Other materials in different forms serve to punctuate and supplement the various services, but these two formats cover most of the structure of the prayer services included in the siddur.

Changes and Developments

Although the basic format for the prayer services was worked out during the Talmudic period, the siddur continued to grow incrementally as new materials were added into the earlier structure. This conservatism begins with the one, overwhelmingly consistent stylistic aspect of Jewish prayer: the use and adaptation of biblical language. Another aspects of this conservatism is the reliance on precedents for opportunities to change the established structure.

For example, the Talmud records at the end of the second chapter of Tractate Berakhot (Blessings) the personal prayers of different rabbis upon concluding the Amidah. That precedent opened up the opportunity for all kinds of additions to the service to be tacked on after the recitation of the Amidah. Similarly, a list of morning blessings that the rabbis originally thought should be recited in the home before joining with the community was eventually, due to popular demand, inserted at the beginning of the service. Following this addition, other later materials were also inserted. Many of these later materials include some of the best-loved medieval poetry found in the siddur like Adon Olam (Eternal Lord) and Yigdal (a poetic adaptation of Maimonides‘ principles of faith).

Mystical Influences

The mystical developments did not add too much original content to the liturgy found in the prayer book. But the mystical emphasis on the perfection of the text of the siddur and the mystical meanings found in the numbers of words or letters in the various prayers led, on the one hand, to an even greater textual conservatism, and, on the other hand, the beginning of elaborate commentaries on the prayer book that explained the mystical significance of the texts. The genre of siddur commentary has grown since those early, mystical works. Since the prayer book is among the most accessible and widely known Jewish texts, many scholars realized that siddur commentary would be a very effective educational tool.

Although the forms of the prayer services were laid out during the time of the Talmud, the first real siddur was not written until the ninth century when various Babylonian geonim (Jewish leaders) worked out the actual “canon” of the synagogue service. Even so, differences remained and continued to develop between different communities, especially between Ashkenazi and Sephardi communities. In modern times, different denominations of Judaism have developed their own prayer books, and different individuals have published their own siddurim. Modern prayer books frequently include translations, new commentaries, and the texts for home rituals and observances.

siddur

Pronounced: SIDD-ur or seeDORE, Origin: Hebrew, prayerbook.

Talmud

Pronounced: TALL-mud, Origin: Hebrew, the set of teachings and commentaries on the Torah that form the basis for Jewish law. Comprised of the Mishnah and the Gemara, it contains the opinions of thousands of rabbis from different periods in Jewish history.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.