Hebrew is one of the oldest spoken languages in the world and the sacred language of the Jewish people. It is the only language ever to be revived as a spoken language — nearly 2,000 years after it ceased being one.

A Brief History of Hebrew

Hebrew was the language spoken in biblical times by the ancient Israelites. One of the original names for this language, and the one it is called today, is ivrit, because it is the language spoken by a people called the ivrim, or the Hebrew people. But it goes by many names in ancient Jewish texts, most frequently lashon hakodesh — the holy tongue.

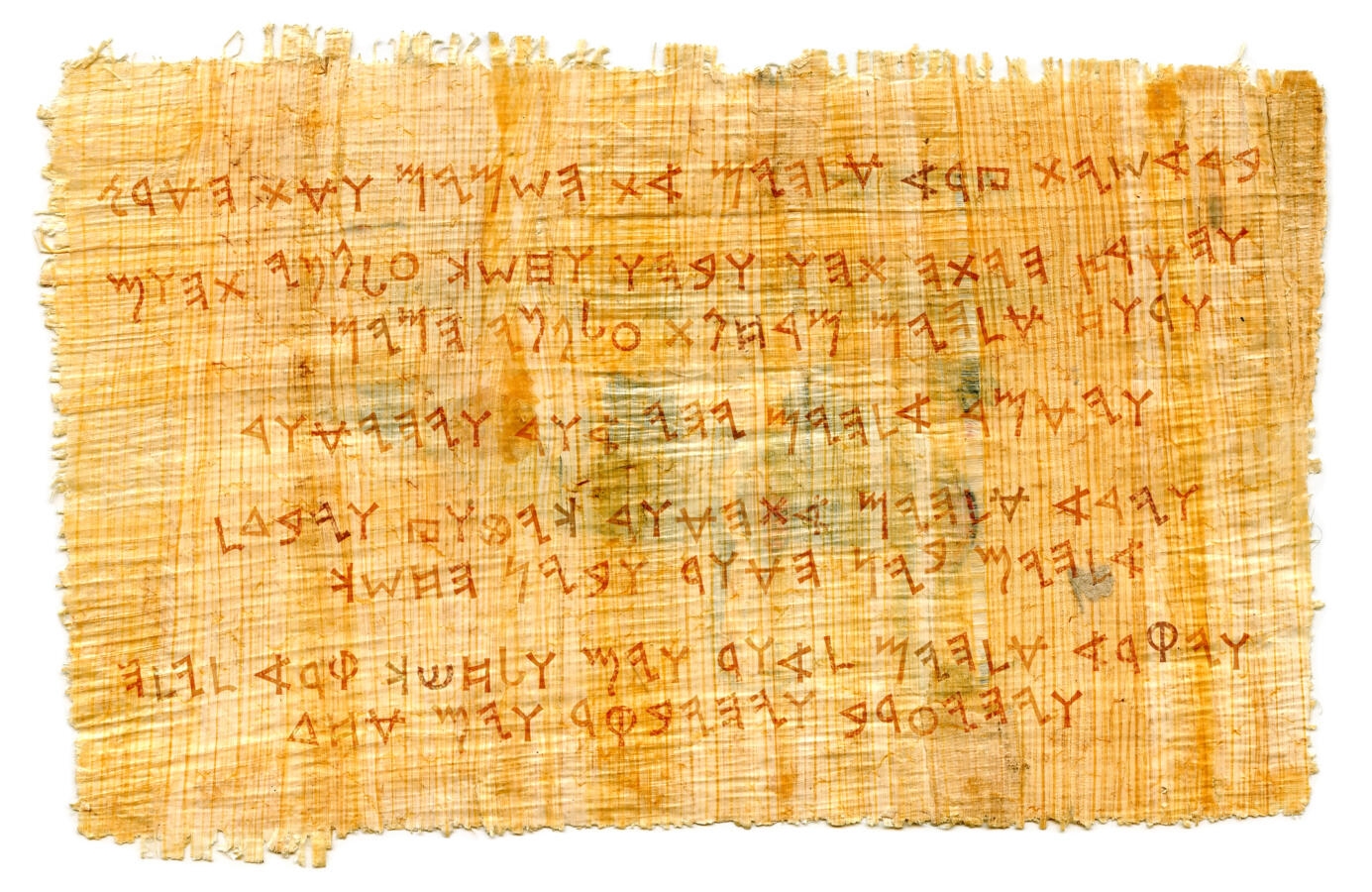

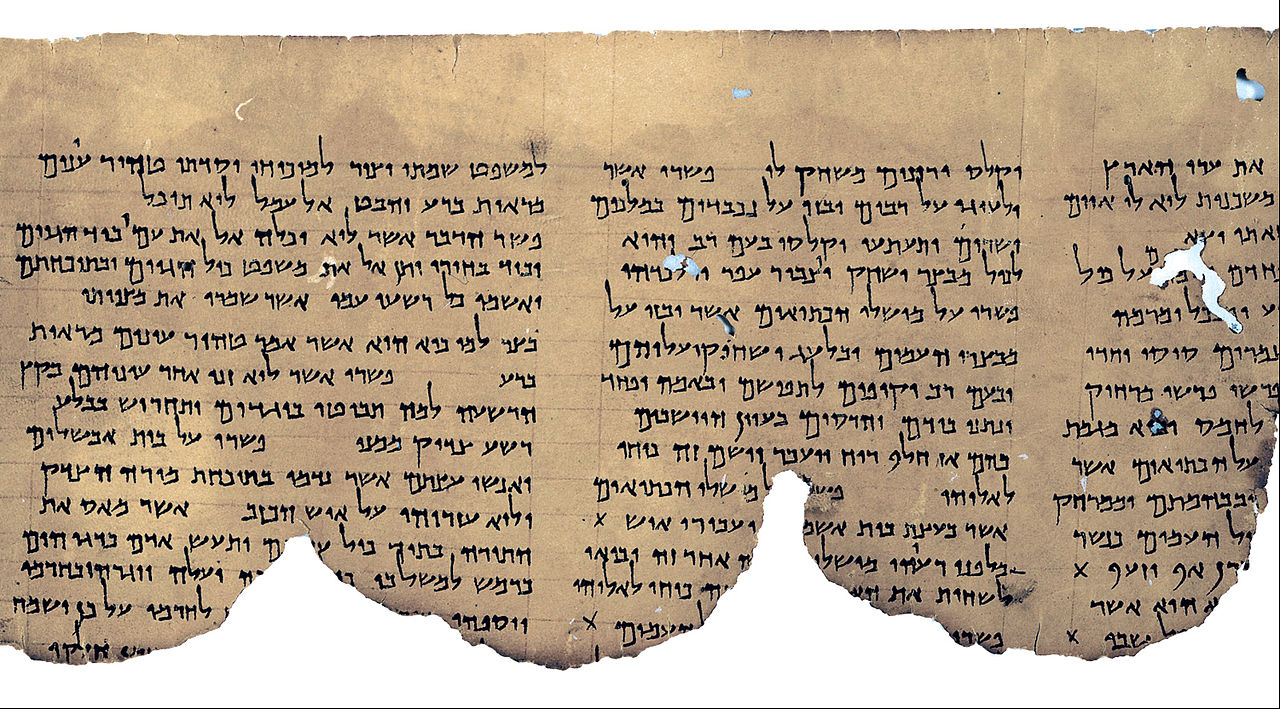

Archaeologists have uncovered examples of written Hebrew that are 3,000 years old, though people only familiar with modern Hebrew script find them indecipherable because they are written in an older alphabet. Scholars refer to this ancient Hebrew script as paleo-Hebrew and ancient rabbis called it libona’ah, perhaps from the word livanah meaning brick or tile — a nod to the blocky shape of the letters. Some of the Dead Sea Scrolls are written in this ancient script and today Samaritan Hebrew continues to use an alphabet derived from it.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Everything changed for the Jewish people and their language in 586 BCE, when the Babylonians destroyed the First Temple and sent a large portion of the populace into exile. In the wake of that disaster, scholars believe, many if not most Jews began to speak other languages, especially Aramaic, which became ascendant with the rise of the Persian Empire less than a century later. In this period, Hebrew did not disappear, but it became the language of scripture and liturgy while other languages were spoken in the street. Also in this period, Jews began to write Hebrew in a new script heavily influenced by Aramaic, a precursor of the modern Hebrew script.

By late antiquity (somewhere between the 2nd and 4th centuries CE), in the wake of the destruction of the Second Temple, Hebrew completely ceased to be a spoken language among Jews. However, it remained an important language of scripture, prayer and learning. Over the next millennium and a half, Jews scattered across the globe spoke the languages of the countries in which they found themselves, but they were able to communicate with other Jews using Hebrew. This common language made it possible for Jews to become prominent global traders in the medieval and early modern periods and kept Jewish communities connected through centuries of dispersion.

Modern Revival

Hebrew is the only known example of a language being revived as a spoken language millennia after it stopped being one. This achievement is due largely to the efforts of one man, Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, who championed Hebrew as the language of the future State of Israel. Many of his contemporaries suggested languages like Yiddish that were already spoken by many Jews should be the Jewish national language. Ben-Yehuda, however, strongly believed that Hebrew was a better choice. He famously raised his son to speak only Hebrew (when no one else on the planet spoke Hebrew as a first language) and developed hundreds of modern words to update the language, eventually producing a 17-volume dictionary. His mission was successful and Hebrew became the official language of the State of Israel when it was created in 1948, 26 years after Ben-Yehuda’s death.

Today, Hebrew is the native language of over 9 million people. The Academy of the Hebrew Language uses Ben-Yehuda’s principles to continually invent and approve new Hebrew words. Because it was largely a language frozen in texts for so long, modern Hebrew is not terribly removed from ancient forms. It is grammatically different from biblical Hebrew, but not wildly so. It is closest to mishnaic Hebrew (a version used to write the Mishnah in the 3rd century), and more dissimilar to later rabbinic Hebrew, which adopted many Aramaic words and phrases.

Sacred Language

Jews refer to Hebrew as lashon hakodesh, the sacred language (Berakhot 13a, Sotah 49b), in part because it is the language of the Jewish Bible, and also because, according to the Jewish scriptures, Hebrew played a key role in the creation of the world. In Genesis 1, God creates the world by speaking Hebrew.

Jewish tradition holds that Hebrew words are brimming with meaning, both manifest and hidden. In the Talmud, Rabbi Akiva is particularly skilled at teasing out the many hidden meanings in Hebrew words, teaching his students to adduce meaning not only from the words, but from individual letters and even the decorations used by scribes to illuminate the script. The Talmud records:

When Moses ascended on High, he found the Holy One, Blessed be He, sitting and tying crowns on the letters of the Torah. Moses said before God: “Master of the Universe, who is preventing You (from giving the Torah without these additions)?” God said to him: “There is a man who is destined to be born in several generations, and Akiva ben Yosef is his name. He is destined to derive from each and every thorn of these crowns mounds upon mounds of halakhot (laws).

Menachot 29b

Another Jewish way of deriving meaning from Hebrew is through the practice of gematria, Hebrew numerology. Gematria assigns a numerical value to each letter of the Hebrew language, through which one can calculate the value of words and phrases to find additional insights. The best-known example is the Hebrew word chai (חי), meaning life, which has the value of 18. Eighteen is considered a lucky number and Jews often give monetary donations in multiples of it. The Talmud contains many other examples of meanings derived through gematria. For instance, hasatan, meaning “the satan,” has the numerical value of 364. The rabbis explain that this is because the satan is allowed to prosecute humankind for 364 days out of the year, but on Yom Kippur, when humans are atoning and God is judging, he is not permitted to prosecute (Yoma 20a).

Ancient rabbinic authorities disagree as to why Hebrew is a sacred language. Maimonides (Guide of the Perplexed, 3:8) says that Hebrew is sacred because it has no words for things like male and female genitalia, sperm, urine, or excrement — preferring euphemisms in their place. Nahmanides (commentary to Exodus 30:13) disagrees, claiming that Hebrew is sacred because God created the world through Hebrew letters and spoke to the prophets in Hebrew.

Nahmanides was one of many Jewish mystics inspired by the idea that Hebrew was the vehicle through which God created the world. The kabbalists attached many interpretations to the letters themselves, which they believed could be arranged in 70 different ways to write the name of God. Kabbalistic exercises included many meditations on the letters, which were thought to represent various kinds of cosmic forces. This idea found early expression in Sefer Yetzirah:

He hath formed, weighed, transmuted, composed, and created with these twenty-two letters every living being, and every soul yet uncreated.

Sefer Yetzirah 2:2

Today, Hebrew continues to be the dominant language for Jewish prayer around the world. Though some Jewish movements have experimented with more prayer in the vernacular, virtually all Jewish communities conduct a significant component of the prayer service in Hebrew. This remains the case even though most non-Israeli Jews are not fluent in the language and many ancient Jewish sources assert that one can pray in any language.

Want to learn Hebrew one day at a time? Click here to sign up for our Hebrew Word of the Day email.

Mishnah

Pronounced: MISH-nuh, Origin: Hebrew, code of Jewish law compiled in the first centuries of the Common Era. Together with the Gemara, it makes up the Talmud.

Talmud

Pronounced: TALL-mud, Origin: Hebrew, the set of teachings and commentaries on the Torah that form the basis for Jewish law. Comprised of the Mishnah and the Gemara, it contains the opinions of thousands of rabbis from different periods in Jewish history.