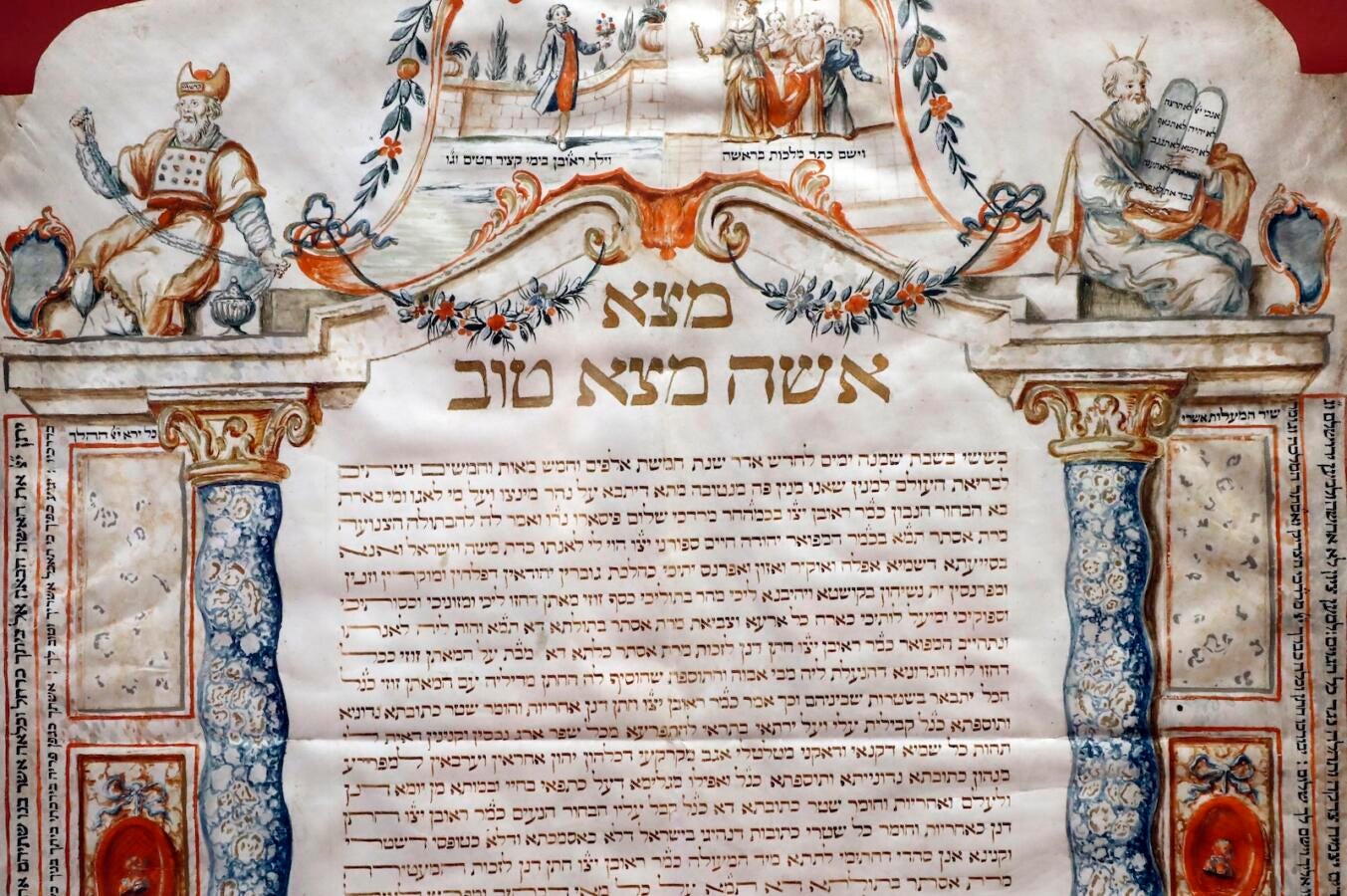

Almost every Jew encounters Aramaic at some point. Although it is not the sacred tongue of Hebrew, nor an iconic Jewish language like Yiddish or Ladino, it surfaces at moments of deep emotion: at funerals, with the recitation of the Mourner’s Kaddish, and at weddings in the ketubah, the marriage contract defining the obligations of the union.

Aramaic also makes its presence felt on holidays. On Yom Kippur, it shows up in the opening Kol Nidre service, often one of the largest synagogue crowds of the year. And on Passover, the seder begins with the passage Ha Lachma Anya (“This is the Bread of Affliction”), which invites the hungry to join in the holiday meal, and concludes with the curious song Chad Gadya. Both are in Aramaic.

Aramaic is also a spoken language, but in modern times, there are few Jews left for whom it is their mother tongue. At the same time, young men and women who study in yeshiva spend much of their days poring over the text of the Babylonian Talmud, which is written primarily in Aramaic.

All these examples reflect Aramaic’s layers. Each stage in the development of Aramaic has its own grammar and vocabulary, its own flavor and texture. To grasp these distinctions, we need to step back and follow Aramaic’s long path through history.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Origins and Spread

Aramaic first emerged as the language of the Arameans, who lived in what is now Syria and northern Iraq. The earliest evidence of Aramaic comes from royal inscriptions dating back to the 9th century BCE. This is what scholars call the period of Old Aramaic. It sounds strikingly close to biblical Hebrew, and that closeness endured, with some verbal forms appearing only in biblical Hebrew and in Old Aramaic. The rabbis who created the Mishnah, Talmud and Midrash wrote in both Hebrew and Aramaic. Even in the Middle Ages, Hebrew and Aramaic stood side by side as literary partners. In many ways, their histories are inseparable.

Unlike Hebrew and its related Canaanite languages, Aramaic spread widely as the Aramean tribes moved across the Assyrian and Babylonian empires beginning in the early first millennium BCE. In the 8th century BCE, the Neo-Assyrian Empire made Aramaic its language of administration. When the Persians under Cyrus conquered Babylon in the 6th century BCE, they too used Aramaic, even though the Persians are not a Semitic people. This official form of Aramaic, known as Imperial Aramaic, became standardized across the Near East and for centuries served as the language of government.

It is in this setting that we encounter the earliest Jewish texts in Aramaic. Two biblical books include substantial sections in the language. The earlier one is Ezra, which describes events from the 5th century BCE but was probably composed in the 4th century BCE. The later work is Daniel, an apocalyptic composition filled with visions and otherworldly imagery. Although it frames itself as an ancient account set in the Babylonian and Persian courts, scholars generally agree that it is a literary fiction, an invented myth about ancient characters, composed much later, in the Hellenistic period around the 2nd century BCE.

Aramaic and Jewish Life

When the Greeks and Romans gained control of the region, they replaced Aramaic with their own languages for administration. Still, the prestige of Imperial Aramaic lingered, especially in legal writing. We see this in documents from the Bar Kokhba Revolt (2nd century CE), the Babylonian Talmud (redacted sometime between the 5th and 7th centuries CE), and in the halakhic literature of the Geonic period (7th–11th centuries CE). This legacy explains why the ketubah, the Jewish marriage contract, is written in deliberately archaic Aramaic, preserving the tradition of Imperial Aramaic as the authoritative language for legal documents.

Aramaic was the spoken vernacular of the Jews from the Babylonian exile through the late Second Temple period and into the Roman era. This shift from Hebrew to Aramaic explains the rise of Aramaic translations of the Bible, whose very existence shows that many Jews no longer understood Hebrew and needed scripture in Aramaic. Over time, these translations became canonical; to this day, Yemenite Jews still read them aloud in synagogue on Shabbat.

After the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, two main centers of Jewish life emerged, in Babylon and Israel. From these centers came the two most influential works in the Jewish tradition — the Babylonian Talmud and the Jerusalem Talmud. Though they deal with similar subjects, each was written in a different Aramaic dialect: the Babylonian Talmud in an eastern dialect and the Jerusalem Talmud in a western one. As a result, the Babylonian Talmud’s language is closer to Syriac, the official language of the Eastern Church, while the Jerusalem Talmud’s grammar resembles the dialects used by the Western Church and by the Samaritans of the region.

Later Transformations

With the Arab conquest around the 7th century CE, Jews stopped speaking Aramaic as their everyday language. Still, Aramaic remained alive through the daily study of the Babylonian Talmud and through the creation of newer works.

The Zohar is likely the most prominent example. The central mystical text of the Middle Ages was composed in the 13th century in Aramaic. Its authors sought to imitate the language of the Jerusalem Talmud and the Midrash to lend their work an aura of antiquity, though their grammar was largely Babylonian. The result was a uniquely medieval phenomenon: Aramaic writings that mixed dialects from different periods and frequently incorporated Hebrew — the language their authors knew best. Liturgical poems (piyyutim) were also composed in Aramaic, weaving the language even more deeply into Jewish prayer and song.

This is the background of the layered Aramaic we still encounter in Ha Lachma Anya at Passover and during Kol Nidre on Yom Kippur. The blend of grammatical features drawn from different stages only heightens the sense of mystery: a language so close to Hebrew, yet just strange enough to sound esoteric and otherworldly.

Modern Echoes

Beyond Jewish life, Aramaic endured for centuries as a spoken language across the Middle East, from Iran to Turkey, though its dialects absorbed layers of Persian grammar and vocabulary along the way. Jews of Kurdistan proudly called their speech the “language of the Talmud,” just as local Christians cherished theirs as the “language of Jesus.” These were not claims of linguistic accuracy but expressions of identity, of belonging to a sacred past. That’s because the dialects changed so much over the years that the sages of the Talmud or Jesus himself would hardly have followed a simple conversation.

Today, only a few Christian and Muslim enclaves still keep Aramaic alive as a vernacular. For example, Syria’s villages of Maaloula, Jubbʽadin and formerly Bakhʽa continue to use Western Neo-Aramaic in daily life, among both Christian and Muslim residents. Likewise, in northern Iraq and the Kurdistan region, Christian communities are actively engaged in preserving Aramaic in areas such as Erbil. While these Aramaic-speaking enclaves persist, the Jewish dialects stand on the edge of extinction. With the migration of Kurdish Jews to Israel in the mid-20th century, the last native speakers are now passing from the world.

And yet Aramaic has never disappeared. On the pages of the Talmud and in the synagogue, in study halls and in prayer, it continues to sound. Whether in an authentic dialect or a hybrid form, Hebrew’s sister language has never left Jewish lips.