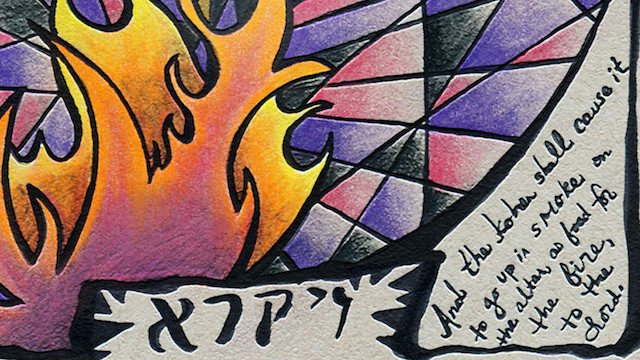

Commentary on Parashat Vayikra, Leviticus 1:1-5:26; Deuteronomy 25:17-19

In cheder, the Hebrew elementary school of late 19th- and early 20th-century Eastern Europe, boys began learning Torah at age 5. They began with the book of Vayikra, which we call in English “Leviticus.” This practice is still followed in contemporary schools that follow the cheder model, mostly in the haredi Orthodox (ultra-Orthodox) world. I’m fascinated that they begin their studies not with Torah’s opening words “As God was beginning to create…,” but instead with Vayikra el-Moshe “and God called to Moses.” That is to say, they begin with Leviticus — with its sprinkled blood and burnt kidneys and laws about nakedness that couldn’t be further from the post-sacrificial Judaism that most contemporary Jews know and cherish.

It’s easy to shy away from Leviticus. The middle book of the Torah, Leviticus is rife with the details of a sacrificial system we haven’t practiced in the better part of 2,000 years. (And most contemporary Jews have no interest in returning to pre-rabbinic Judaism, which makes Leviticus even more alien and alienating). The first portion in the book of Vayikra (Leviticus) is also called Vayikra. The word means “And God Called.”

The first word of this biblical book is characterized by a textual oddity. In Torah scrolls, which are still handwritten with quill and ink on parchment, the final letter of that first word is always written extra-small. (It looks like this.) The silent aleph (א) at the end of the word is written in miniscule.

Without that aleph, the word would mean “and God happened upon.” With the aleph, it means “And God called.” Midrash teaches that Moses wanted to write “vayikar,” without the final aleph — as though God had merely happened upon him. But God insisted otherwise. God didn’t just “happen upon” Moses, but called out to Moses on purpose! In the end, they compromised: The letter is there, but it’s tiny.

Set aside for the moment whether or not you believe the Torah was given to Moses in full on Mount Sinai, and whether or not you believe that the details of scribal practice are divinely foreordained. What interests me about this story — this push-and-pull between Moses’ humility and God’s insistence that Moses has a role — is that it’s in our canon in the first place.

One way of reading Torah suggests that every character in Torah can be found within the reader. This suggests that we too have moments of being humble like Moses — and we too have moments of recognizing that we are not merely an accident of happenstance.

I can relate to Moses’ humility. Who am I, after all, to hear a direct call from the One? But in this telling, at least, God insists otherwise. God calls us into service. God knows that we have gifts the world needs, even if we don’t always see them in ourselves. Our lives are no coincidence. We are placed here for a reason.

The difference between Vayikra with an aleph at the end (“And God called”), and vayikar (“and God happened upon”) without the aleph, is tiny (especially when the aleph itself is tiny). The difference between a life where God’s presence is manifest in everyday miracles and a life where divinity feels absent may be equally so. It’s a matter of epistemology, not ontology. If I’m awake to God’s presence in what’s unfolding for me right now, then I may feel (like Moses) “called” — and if I’m not awake to that presence, it may seem to me that life “just happens.” The difference between feeling as though life is a series of happenstances, and feeling as though life has purpose and meaning, lies in our willingness to tune our internal radios in order to hear what’s concealed within the sounds of silence.

Aleph is a silent letter. One Hasidic teaching holds that it contains the entirety of Torah compressed within it. Because it’s the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet, it can represent the infinite, the many, within the singularity of the One. In the Torah as we’ve received it, this aleph at the end of the word Vayikra is tiny, like a seed or a spark. It’s a kernel of potential.

If we attune ourselves to divine Presence, then the first word of this Torah portion is Vayikra: “And God Called.” If we shrug off the possibility of divinity or the experience of wonder, then the first word becomes simply vayikar — “And God happened upon.”

Perhaps when the work of healing creation is complete, the tiny aleph in the word Vayikra will be as large as its fellows: Because we will have done the work of figuring out how to aptly balance ego and humility, awareness of our insignificance with awareness of our power. Just as silence can contain the promise of every possible sound, the silent aleph can contain the promise of every possible letter and word. What will we hear if we quiet our minds and listen for what reverberates in the silent aleph at the end of this Torah portion’s first word?

cheder

Pronounced: KHAY-der, or KHEH-der, Origin: Hebrew, literally “room” in Hebrew, the cheder is a traditional Jewish elementary school.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.