The Zohar is the most important work of Jewish mysticism and one of the central sacred texts of Jewish tradition. It emerged in late 13th-century Spain, most likely authored by the kabbalist Moses de Leon, though it claims to be an ancient text revealed by Rabbi Shimon bar Yohai in the second century. Structured as an esoteric commentary on the Torah, the Zohar weaves a rich tapestry of midrashim, parables and mystical insights to unveil the hidden nature of God and the universe.

To understand what the Zohar is, it’s helpful to know something about Kabbalah, a particular form of Jewish mysticism that emerged in the 13th century. The mystical quest for encounter with God is arguably as old as Judaism itself. Biblical figures like Abraham and Moses had direct encounters with God, as did the Jewish prophets. Ezekiel in particular had an ecstatic vision of God and the angels that provided significant fodder for the imaginations of later Jewish mystics. Literature from the rabbinic period daringly described God’s physical form and retinue in startling detail.

Kabbalah built on these earlier traditions but took a more intimate view of God, seeing God as more closely (and vulnerably) enmeshed with humanity and the world. It can be seen as a reaction against the rationalist approach of Maimonides, the medieval philosopher who saw God as perfect and all-powerful, distant and self-sufficient, an unmoved mover of the universe. Maimonides’ God had no need for people to fulfill the divine commandments, which were simply mechanisms to teach wisdom and ethics. Kabbalists rejected this view, contending that the mitzvot are of immediate and vital importance to the world and to God. For the kabbalists, God is neither remote nor self-sufficient, but omnipresent and wholly invested in the world.

These are among the beliefs that animate the Zohar, which is structured as a series of interpretations of the Torah, many related as discussions between Rabbi Shimon bar Yohai and his nine principle disciples: his son Rabbi Elazar, Rabbi Abba, Rabbi Yehudah, Rabbi Yitzhak, Rabbi Hizkiyah, Rabbi Hiyya, Rabbi Yose, Rabbi Yeisa and Rabbi Aha.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

The Zohar’s ideas are difficult to capture in everyday language, often relying on metaphor, parable and suggestive language to explain itself. This makes it challenging to capture its tenets in prose, but several ideas are central. These include:

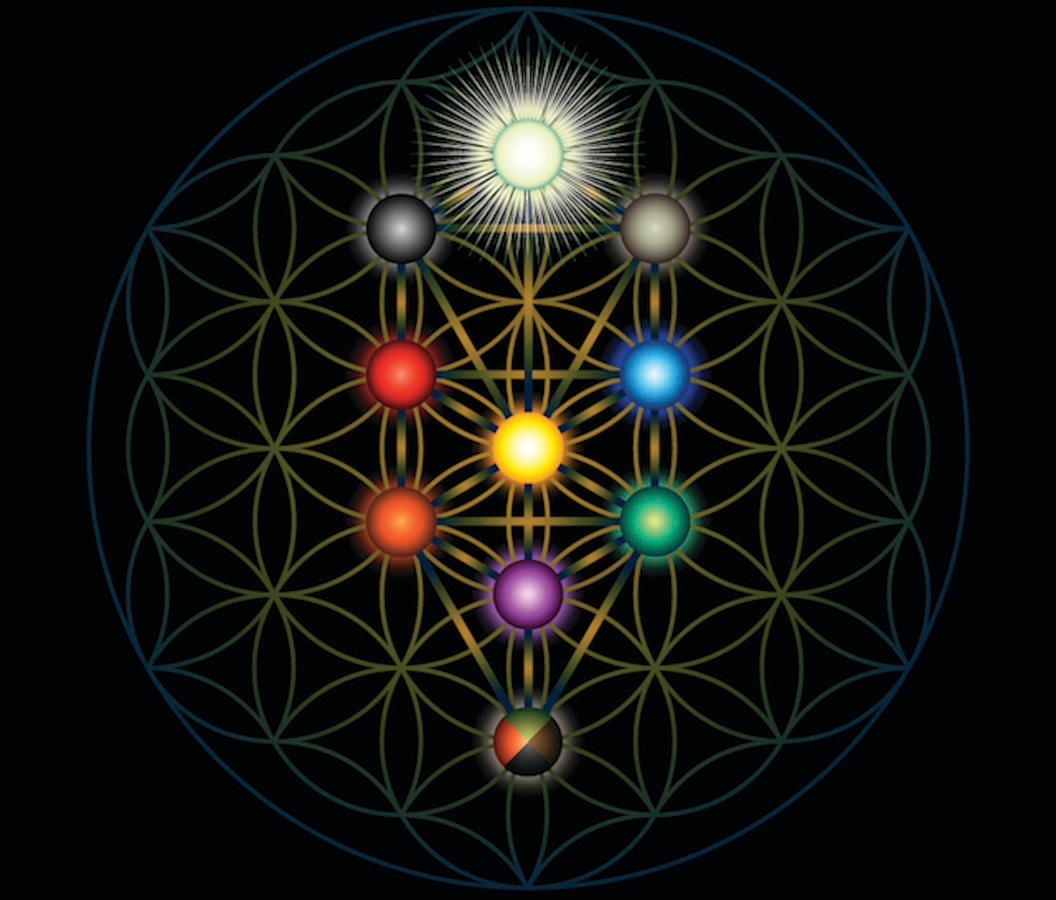

The Ten Sefirot: In the thinking of the Zohar, God’s innermost self, the Ein Sof (Without End), is unknowable. But other parts of God are not. According to the Kabbalists, God enters the world through ten emanations, or sefirot:

- Keter (Crown)

- Hochmah (Wisdom)

- Binah (Understanding)

- Hesed (Lovingkindness)

- Gevurah or Din (Strength/Justice)

- Tiferet (Beauty/Harmony)

- Netzach (Eternity/Victory)

- Hod (Splendor/Glory)

- Yesod (Foundation)

- Malkhut or Shekhinah (Kingdom/Sovereignty)

Keter is the highest as well as the most abstract and remote. It is followed by Hochmah and Binah, the primordial Father and Mother emanations. These, in turn, birth the next seven sefirot. The lowest and most imminent sefirah is Shekhinah, God’s indwelling presence on earth.

The condition of and relationship between these sefirot is not only vital to the world but strongly influenced by human action. Harmony and balance between the sefirot is therefore one of the highest goals of human behavior. Ethical living, performance of mitzvot and prayer can all help to bring the sefirot into better balance.

Dualities: The kabbalistic fascination with dualities is clear from a cursory look at the sefirot, several of which partnered to birth new emanations. Indeed, the male/female duality is arguably one of the most important in Kabbalah. The duality between good and evil also plays a significant role, with kabbalistic thought making copious room not only for God’s goodness, but also demonic forces of evil. Equally, the duality of exile and return — both Israel’s exile from the promised land and the exile of aspects of the divine from God itself — pervades kabbalistic thought.

Interconnection of the Cosmos: In kabbalistic thought, the entire world is interconnected and interdependent, in ways both obvious and hidden. Every action has a measurable affect and influence on the rest of the world. Therefore, every action matters.

Scripture’s Layers: For the kabbalists, Torah is the gateway to limitless secrets of the universe if only one knows how to discern its inner meanings. At times, scripture is conceived as more than a sacred book, but as a living presence that forms a relationship with the one who studies it.

Cleaving to God: The highest form of spiritual expression is clinging to God. This is called devekut (pronounced: d’vay-KOOT). The term appears many times in the Bible, often alongside commandments, suggesting that devekut is realized through obedience to God’s ways. Medieval commentators extended this idea to say that devekut is achieved through imitation of God. And the kabbalists took it one step further, believing that devekut is union with God achieved through mystical practices, meditation, prayer, study and aligning oneself with the flow of divine energy.

In its early years, the Zohar was studied mainly in small circles of devoted kabbalists. But after the expulsion of Spanish Jewry in 1492, the Zohar’s influence grew dramatically. Some scholars argue that many exiles, shaken by persecution, found solace in its worldview. Others think that the Zohar contained ideas that meshed nicely with those found in the lands that ultimately absorbed Jewish exiles.

By the 16th century, the town of Safed in northern Israel, located near the traditional tomb of Rabbi Shimon bar Yohai, became a kabbalistic hub. Leading figures such as Moses Cordovero and Isaac Luria settled there, combining the teachings of the Zohar with their own mystical systems. Their work helped establish Kabbalah as a major force in Jewish life.

In later centuries, the Zohar continued to shape Jewish movements across the world. It played a central role in the failed 17th-century messianic movement of Shabbetai Zevi, and in Eastern Europe it became a foundation for Hasidism, whose leaders often quoted and wrote commentaries on the text. Even the Vilna Gaon, a critic of Hasidism, revered the Zohar and encouraged its study. Among Sephardic and Mizrahi Jews, the Zohar has been widely read and regarded as a sacred book up until the present.

With the rise of the Enlightenment in Europe, Kabbalah lost standing in many Jewish communities. Both Reform and Orthodox leaders in Western Europe tended to set aside or downplay mystical texts, and the Zohar was less central to mainstream Jewish practice. Still, in Hasidic and Sephardic circles, its influence endured.

Today, the Zohar is experiencing renewed attention. A growing interest in spirituality and mysticism worldwide has brought new readers to kabbalistic texts. In Israel, pride in Sephardic and Mizrahi heritage, along with the founding of new kabbalistic academies, has also fueled a revival of study.

Hasidic

Pronounced: khah-SID-ik, Origin: Hebrew, a stream within ultra-Orthodox Judaism that grew out of an 18th-century mystical revival movement.

Talmud

Pronounced: TALL-mud, Origin: Hebrew, the set of teachings and commentaries on the Torah that form the basis for Jewish law. Comprised of the Mishnah and the Gemara, it contains the opinions of thousands of rabbis from different periods in Jewish history.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.

Zohar

Pronounced: ZOE-har, Origin: Aramaic, a Torah commentary and foundational text of Jewish mysticism.