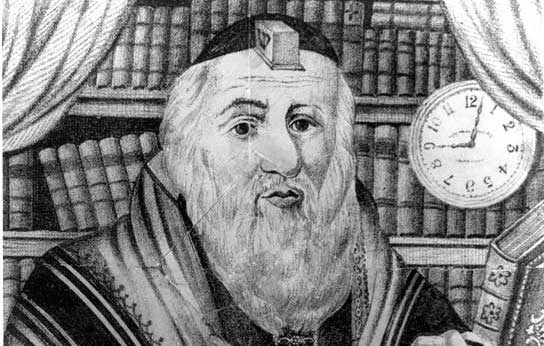

Rabbi Elijah ben Solomon Zalman Kremer — better known as the Vilna Gaon or sometimes as HaGra, an acronym for his Hebrew title, Hagaon Rabbi Elijah — was a renowned Jewish scholar who lived in Vilna (now Vilnius), the capital of Lithuania, in the 18th century.

A talmudist, kabbalist and a leading opponent of the then emerging Hasidic movement, the Vilna Gaon authored commentaries on many canonical Jewish texts, including the Shulchan Aruch code of Jewish law and the Talmud. Much of his writing takes the form of annotations and emendations to classical texts that were written down after his death.

The gaon was renowned as the leading Torah authority of his generation and his thinking had an enormous influence on the development of European Jewry in the modern era. Among his disciples was Chaim of Volozhin, founder of the famed Yeshiva of Volozhin, which operated for a century and became the model for many of the Lithuanian-style yeshivas still operating today.

Born in 1720, the gaon (Hebrew for “genius”) was said to have demonstrated prodigious skills in Torah study from an early age. One story has it that he had memorized the Bible by age four. Another relates that he gave his first public discourse at seven. Equally prodigious was his commitment to studying. Admired as much for his asceticism as for his genius, for decades he slept little and spent most of his waking hours in seclusion with holy texts.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Rabbi Elijah was also well versed in secular sciences, believing understanding of Torah was enhanced by knowledge of the natural world. According to one (almost certainly apocryphal) legend about him, the gaon composed a mathematics treatise, Ayli Meshulash, during time spent using the bathroom. Since it’s forbidden to study Torah in the bathroom, and the gaon was engaged in Torah study virtually all the time and bathroom time was his only opportunity to write on other matters.

But the gaon was perhaps most notorious for his opposition to the Hasidic movement, which began to expand in eastern Europe in the 18th century. Though the gaon was himself a student of Jewish mysticism, which formed the basis of much Hasidic thought and practice, he believed it should remain the sole province of elite scholars and not popularized as the Hasidic masters were doing. Opposition to Hasidism was concentrated in Vilna and the gaon became the de facto leader of what came to be known as the misnagdim — literally “the opponents.”

The gaon’s opposition was fierce. He believed that the Hasidim were heretics and he issued orders of excommunication — herem in Hebrew — against them. In 1781, the gaon signed one such letter of excommunication along with other Jewish leaders. Ultimately, the opposition was for naught and Hasidism continued to spread throughout Eastern Europe and eventually to Jewish communities in Israel and the West. By the 20th century, the schism was all but over, as both Hasidim and misnagdim set aside their differences to join forces against the rising tide of secularism.

The gaon died in 1797 at the age of 77 and buried in Vilnius. Today he is revered not only by Jews, but by his Lithuanian countrymen. The state Jewish museum in Vilnius is named for him and the Lithuanian government issued commemorative stamps featuring the gaon in 1997, on the 200th anniversary of his death.

Hasidic

Pronounced: khah-SID-ik, Origin: Hebrew, a stream within ultra-Orthodox Judaism that grew out of an 18th-century mystical revival movement.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.