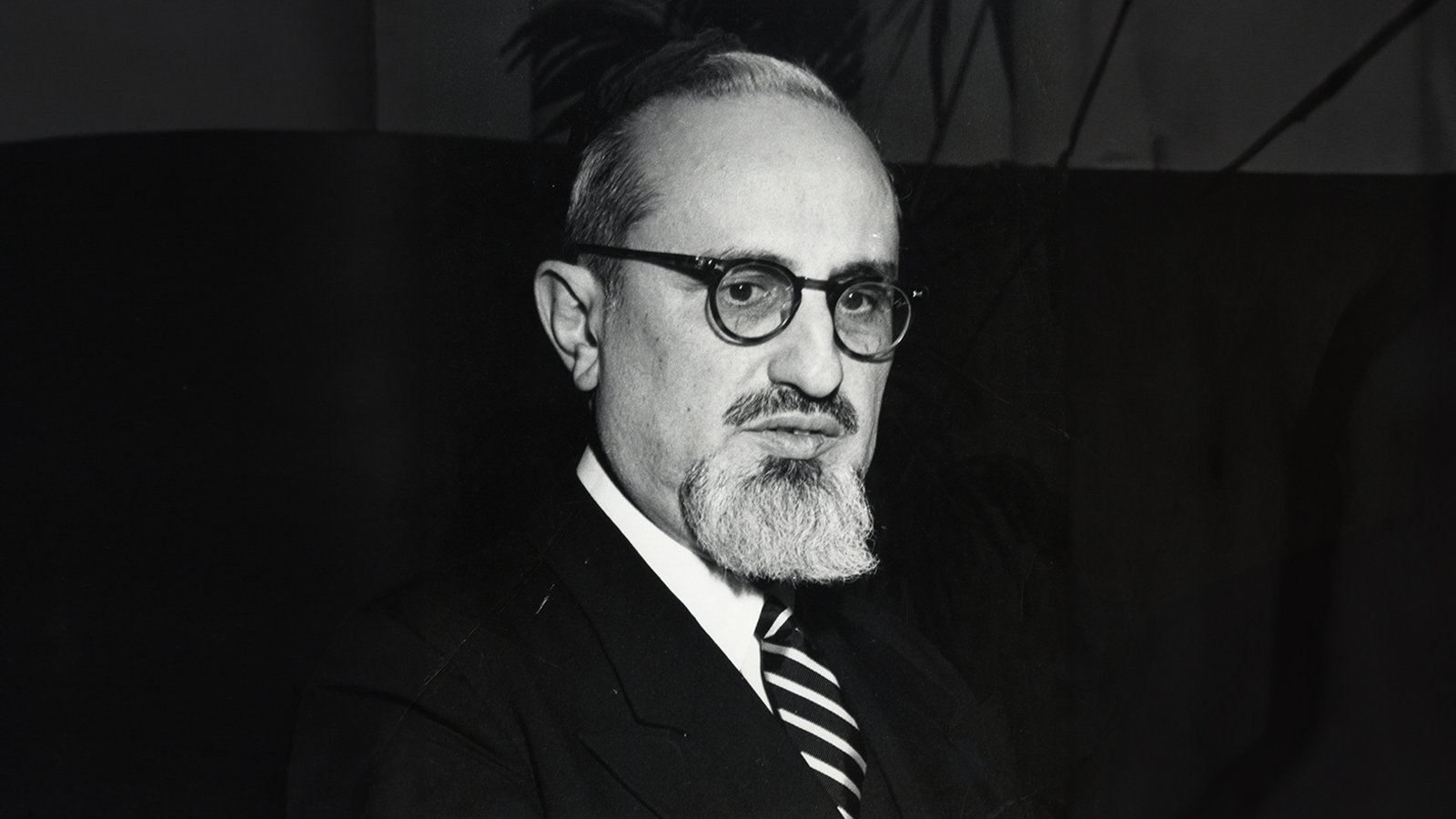

Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik was a renowned talmudist, halachic authority and theologian and one of the most creative and influential Jewish thinkers of the 20th century. Known to his followers as The Rav (literally, “the rabbi”), he ordained thousands of Orthodox rabbis over the course of his career and his students and philosophy continue to impact the Jewish world today.

A scion of the fabled Brisk dynasty of talmudic scholars, Soloveitchik was born in 1903 in Pruzhany, Belarus, to Rabbi Moshe Soloveichik and Peshka Feinstein. His paternal grandfather was Rabbi Chaim Soloveitchik, creator of the intellectually innovative Brisker method of Talmud study, and his great-grandfather was Rabbi Yosef Dov Soloveitchik, a legendary talmudic scholar known as the Beis HaLevi. On his mother’s side, Soloveitchik could trace his ancestry to the renowned biblical and talmudic commentator Rashi. His family was also highly influenced by another great early modern Jewish thinker and scholar, Chaim of Volozhin, who was the primary disciple of the Vilna Gaon. He was also a first cousin on his mother’s side of Rabbi Moshe Feinstein.

In his youth, Soloveitchik was unique for studying with his father, Moshe Soloveichik, and with private tutors, rather than in a yeshiva or in a more formal Jewish educational setting—a somewhat ironic fact considering that the Brisker method is the predominant method of Talmud study in most contemporary yeshivas. Moshe instructed his son in this method, which analyzes talmudic debates through the prism of philosophical and jurisprudential concepts. Soloveitchik became a master of this method, though he was unique within his family and in the wider yeshiva world of that era for pursuing secular studies at an elite level. Soloveitchik went to Warsaw to study philosophy, and then later to Berlin, where he received his doctorate in 1932, writing his dissertation on the thought of Hermann Cohen, a 19th-century neo-Kantian philosopher.

In 1932, Soloveitchik moved to the United States, settling in Boston and founding the Maimonides School, a co-ed Jewish day school (and later high school) at a time in which religious co-education was rare. (Soloveitchik’s support of advanced Jewish education for women would remain consistent throughout his life, as evidenced by his endorsement of Yeshiva University’s Stern College for Women.) In 1941, Soloveitchik began a teaching career at Yeshiva University in New York that would last for nearly a half-century. Soloveitchik was first brought to YU (where his father was already teaching Talmud) to teach philosophy, but as his talmudic genius was recognized, he was appointed as one of the school’s roshei yeshiva (heads of Talmud study) and began giving a regular Talmud class. As Soloveitchik’s reputation spread, he was appointed to various positions of leadership in American Jewry. He was named head of the halakhic (Jewish legal) committee of the Rabbinical Council of America (RCA), the principal organization of Orthodox rabbis in the United States, and also the official conferrer of rabbinic ordination at YU’s Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary (RIETS).

In ordaining thousands of rabbis, and educating thousands of others in his intellectually demanding yet popular Talmud lectures, Soloveitchik left a lasting imprint on American Modern Orthodoxy. Though his primary daily activities consisted of rigorous Talmud teaching, Soloveitchik maintained an abiding interest in philosophy and theology, and his influence in these realms of Jewish thinking continues to be felt as well.

In 1944, he published his major work, Ish ha-Halakhah, which was translated into English as Halakhic Man by Lawrence Kaplan in 1983. In Halakhic Man, Soloveitchik provides a phenomenology of a prototypical “halakhic man”— that is, a description of the experience of the inner world of someone who lives and thinks in accordance with the Jewish legal consciousness of his grandfather, Chaim Soloveitchik. Unlike other modern Jewish phenomenologists such as Martin Buber and Emmanuel Levinas, Soloveitchik sought to provide readers with a description not of their experiences, but of the experience of someone who was wholly unlike them. Halakhic Man thus attempted to describe for readers what it would be like to see the world in a new and compelling way.

Soloveitchik’s protagonist is, in his view, an idiosyncratic figure (much as Soloveitchik was himself) who isn’t highly appreciated in the modern world, but deserves to be. In the modern world, according to Soloveitchik, people tend to be either religious in a spiritual, otherworldly sense (what Soloveitchik refers to as “homo religiosus”) or secular intellectuals (which Soloveitchik refers to as “cognitive man”). Soloveitchik proposed a third way: halakhic man, a subtle synthesis of homo religiosus and cognitive man.

Soloveitchik’s model for combining intellectualism with religion and Torah study with secular studies — encapsulated in the phrase “Torah umadda,” which was adopted as the watchword of YU — became a guiding ethos for much of the American Modern Orthodox community. After his death in 1993, his influence continued to grow, with the publication of more and more of his writings, lectures, letters and class notes. Greater attention has also been devoted to his thought in academic articles, dissertations and other scholarly works. At the same time, his formidable yet at-times challenging legacy continues to be vigorously debated.

In the years following his death, a certain amount of revisionism has crept into portrayals of Soloveitchik, with some (often apparently driven by ideological motivations) asserting that he was only a traditional rosh yeshiva who happened to know a bit of philosophy, while others have attempted to present him as a highly modern thinker who would have been even more philosophically radical if his community had been amenable to such avant-gardism.

In his 1993 eulogy for Soloveitchik, one of his most prominent students, Rabbi Dr. Norman Lamm, who would serve as YU president for more than 25 years, suggested that neither portrayal did Soloveitchik justice.

The Rav was not a lamdan [scholar] who happened to have and use a smattering of general culture, and he was certainly not a philosopher who happened to be a talmid hakham, a Torah scholar. He was who he was, and he was a simple man. We must accept him on his terms, as a highly complicated, profound, and broad-minded personality, and we must be thankful for him.

Talmud

Pronounced: TALL-mud, Origin: Hebrew, the set of teachings and commentaries on the Torah that form the basis for Jewish law. Comprised of the Mishnah and the Gemara, it contains the opinions of thousands of rabbis from different periods in Jewish history.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.

yeshiva

Pronounced: yuh-SHEE-vuh or yeh-shee-VAH, Origin: Hebrew, a traditional religious school, where students mainly study Jewish texts.

halacha

Pronounced: hah-lah-KHAH or huh-LUKH-uh, Origin: Hebrew, Jewish law.

halachic

Pronounced: huh-LAKH-ic, Origin: Hebrew, according to Jewish law, complying with Jewish law.

mitzvah

Pronounced: MITZ-vuh or meetz-VAH, Origin: Hebrew, commandment, also used to mean good deed.

Shema

Pronounced: shuh-MAH or SHMAH, Alternate Spellings: Sh’ma, Shma, Origin: Hebrew, the central prayer of Judaism, proclaiming God is one.