The Jewish wedding is rich with ceremony, beginning with the announcement of intent to marry and ending with seven days of celebration.

Are you planning a Jewish wedding? Let us help out! Sign up for Breaking the Glass, an email series that will help guide you to the wedding that’s right for you!

Some couples have revived a betrothal ceremony, called tenaim, where the engagement is announced, a document of commitment read aloud, and a piece of crockery shattered. The original tenaim, announced when two families had agreed on a match between their children, is still celebrated today by some traditional Jews.

On the Sabbath preceding the wedding, the groom has (and in liberal congregations, the bride and groom both have) an aufruf (in Yiddish, “calling up”) in which he (and/or she) recites blessings over the Torah reading and is showered with candy.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Traditionally, a bride takes her first trip to the mikveh (ritual bath) the day before the wedding, the first of monthly visits that will extend as long as she menstruates. Mikveh signifies that a woman and her husband are again allowed sexual contact, seven days after her menstrual flow ends. This mikveh immersion signifies rebirth and reflects the upcoming change in personal status.

A traditional Jewish wedding begins with separate receptions for the groom and the bride. The groom presides over a tish (literally, “table”), around which the guests sing and make toasts, and the groom delivers a scholarly talk. The ketubah, or marriage contract, is traditionally signed at the tish before two witnesses, and the groom accepts the obligations by a legal consent process called kinyan. In the liberal movements weddings begin with a ketubah signing that includes both bride and groom.

All traditional couples and many liberal ones choose to do the bedeken ceremony in which the groom covers the bride’s face with a veil. Reasons for veiling range from emulation of the matriarchs, who veiled themselves, to bridal modesty, to the groom performing his obligation to clothe his wife.

For the processional the groom may don a white garment called a kittel, a simple cotton robe that is also worn on Yom Kippur and as a shroud at death, alluding to the seriousness of the day. Some grooms wear a tallit (prayer shawl) instead.

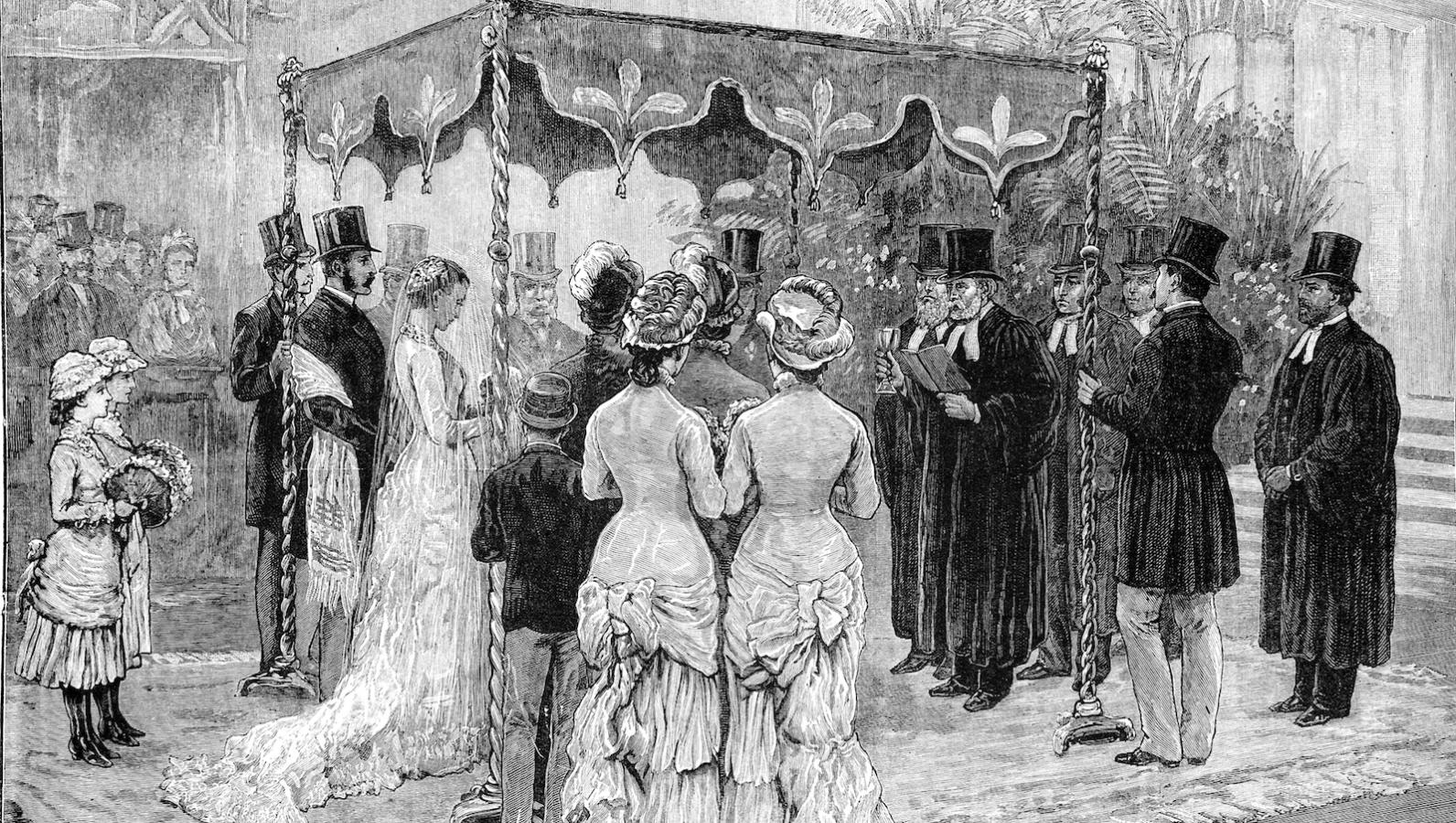

The marriage ceremony is conducted under a chuppah (marriage canopy), which symbolizes the new home that the bride and groom are creating together. In a traditional wedding the bride circles the groom, but in modern weddings both may circle each other or the custom may be dropped altogether.

The Jewish wedding ceremony combines two formerly separate ceremonies: erusin (betrothal) and nissuin (marriage). In traditional communities erusin is still observed separately.

The betrothal involves two blessings, one over wine and the other reserving the couple for each other and forbidding them to have relationships with anyone else. This blessing reflects an earlier practice in which the bride and groom did not consummate their marriage until about a year after the formal betrothal, when the bride moved into the groom’s home.

Next the groom performs the act that formalizes the marriage: He places the ring on the bride’s index finger and recites in Hebrew, “Behold, by this ring you are consecrated to me as my wife according to the laws of Moses and Israel.” In liberal ceremonies the wife may also present a ring, usually accompanied by a biblical phrase rather than the legal formula, although in many cases, the bride will recite a modified legal formula.

The reading of the ketubah serves as a divider between the betrothal and marriage ceremonies.

The nissuin ceremony involves the recitation of seven blessings, called the sheva berakhot, whose themes include creation of the world and human beings, survival of the Jewish people, the couple’s joy, and the raising of a family. The rabbi raises a cup of wine from which the bride and groom drink after the blessings.

The rabbi or other guests may then address the couple, or this may happen at other points during the ceremony. The ceremony ends when the groom (or in some liberal ceremonies, both bride and groom) shatters a glass. Reasons cited for this custom are to quiet boisterous guests, to remind Jews of the Temple‘s destruction, and to allude to sexual consummation of the marriage.

The bride and groom then go to a yihud (seclusion) room, where they spend some time alone and eat a small snack together to break the pre-wedding fast.

The wedding feast that follows is a seudat mitzvah, a commanded meal–accompanied by good food, dancing, and singing–where it is a mitzvah (commandment) to help the couple rejoice.

After the feast, the grace after meals is recited over one cup of wine, and the seven blessings over another. The two cups of wine are poured into a third, from which bride and groom drink.

In the week following the wedding, bride and groom traditionally feast at the homes of friends and relatives, repeating the sheva berakhot after each meal.

ketubah

Pronounced: kuh-TOO-buh, Origin: Hebrew, the Jewish wedding contract.

mikveh

Pronounced: MICK-vuh, or mick-VAH, Alternate Spelling: mikvah, Origin: Hebrew, Jewish ritual bath.

Yom Kippur

Pronounced: yohm KIPP-er, also yohm kee-PORE, Origin: Hebrew, The Day of Atonement, the holiest day on the Jewish calendar and, with Rosh Hashanah, one of the High Holidays.

bedeken

Pronounced: buh-DEK-in, Origin: Yiddish, part of a traditional Jewish wedding ceremony, when the groom symbolically checks under the bride's veil to make sure he is marrying the right person, an allusion to Jacob accidentally marrying Leah, instead of Rachel, in the Torah.