If the description of God as King or Sovereign has a physical manifestation in Judaism, it is through the decoration of the Sefer Torah, the scroll of the Torah written on parchment. In Ashkenazic (Central and East European) Jewry, the Sefer Torah is dressed in an elaborate cloth mantle, which is frequently decorated with semi-precious stones and a breastplate. In Sephardic (Western European and Arabic) Jewry, the Sefer Torah is kept in its own case, usually made of silver. In both communities, the Sefer Torah is adorned with a crown, also of silver.

As with royalty, an elaborate protocol has developed. When the Torah is lifted, people stand. When the Torah is carried around the congregation, people face it and kiss its mantle out of respect (the parchment is never touched directly). The 16th-century Kabbalist (mystic), Elijah ben Moses de Vidas, described the royal image of the Torah explicitly, “When one carries holy books, one should act as though one is carrying the clothes of the king before the king” (Sefer Reshit Hokhmah). De Vidas is drawing on an idea expressed in the Zohar (the classic work of Jewish mysticism) that most people only see the garments of Torah; some can penetrate through the garments to the body, and the truly enlightened can even glimpse the soul of the Torah.

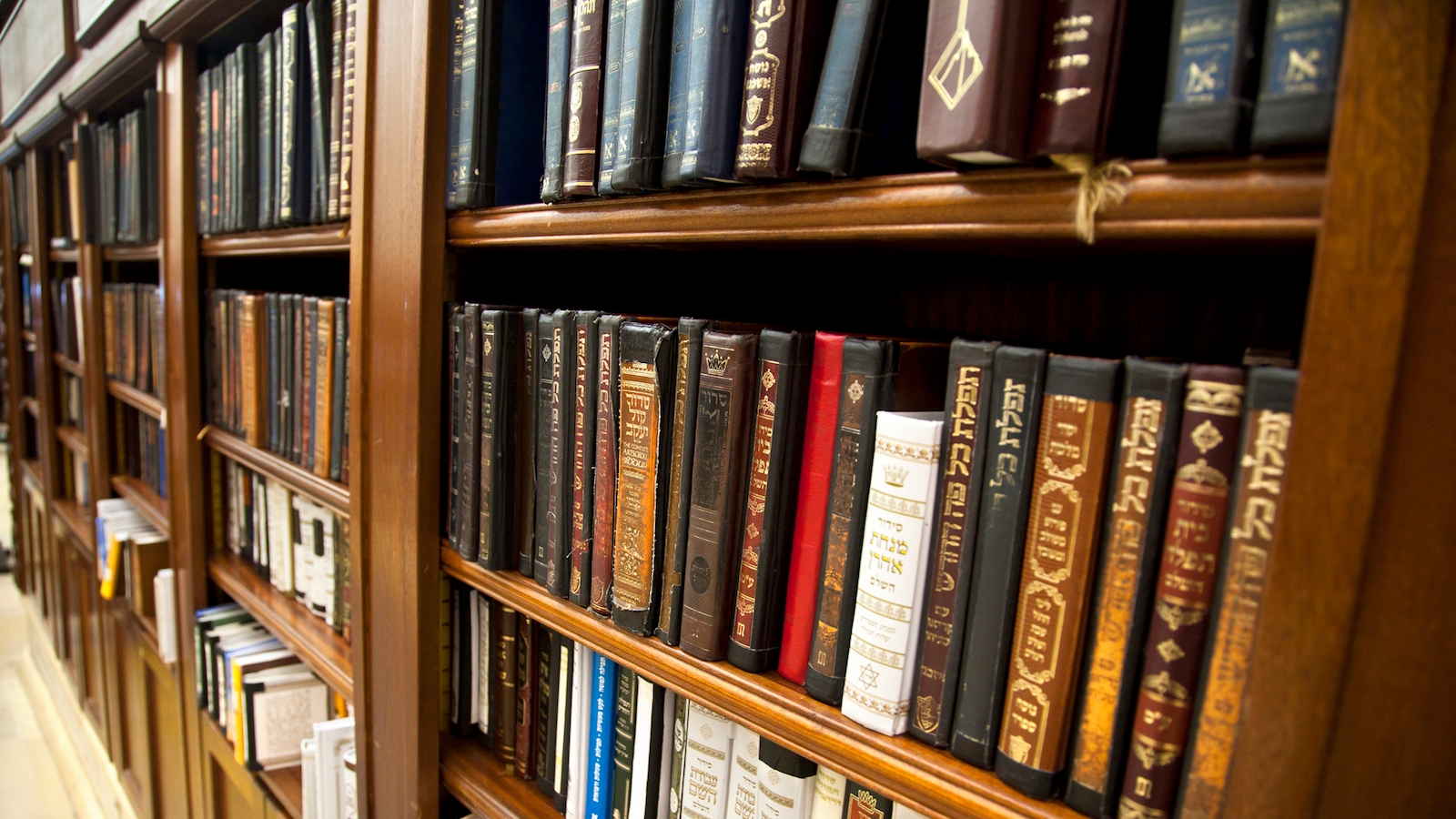

The Hierarchy of Books

As de Vidas expressed, other holy books are only garments for the Torah itself. This image of the Torah’s superiority over other holy books is given concrete expression in Jewish practice. As expressed in the Mishnah, the primary document of rabbinic law, the guiding principle was that one “increases in holiness, and one does not decrease.” A Sefer Torah was at the pinnacle of the ladder of holiness, and one was not allowed to sell a Sefer Torah to buy other synagogue items for that would be a decrease in holiness (cf. Mishnah Megillah 3:1). As a physical expression of this ladder of holiness, the Talmud prescribes that a Sefer Torah can be stacked upon another Sefer Torah, but an individual book of the Five Books of the Torah could not be put on top of a Sefer Torah. Similarly, a single book of the Five Books could be put on top of books of the Prophets or books of the Writings, but not vice versa (Talmud Megillah 27a).

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Eventually, this hierarchy was extended to non-biblical books as well. The medieval work Sefer Hasidim, says that one should not stack books of Talmud (rabbinic discussions of the Mishnah) on top of books of the Bible, and one person was remembered for having separate cabinets for Bible and for works of the “Oral Torah” (rabbinic writings) so people would not associate the holiness of the Bible with the Rabbinic writings (Sefer Hasidim, #141, #908). Interestingly, the same logic also led to the opposite practice. Sefer Hasidim #909 reports:

One person…put a book of oral Torah on top of a book of written Torah. His friend said to him, “Why are you doing that?” He responded, “In order to preserve the book of written Torah, because by covering it with this, I will save it from the dust and ashes falling upon it, and it is better that I cover it with pamphlets of oral Torah and not with another book of written Torah.

It is not clear how one would relatively rank the various non-biblical books, but the idea of “how one stacks one’s books” provides an interesting parallel to the varying levels of authority in a royal aristocracy.

Appropriate Treatment

Parallel to the treatment of holy texts as royalty are other rules dealing with how one treats books. De Vidas said that showing honor to one’s library includes placing books in a prominent place in one’s home, protecting them with heavy pieces of cloth, and using traps to protect the books from destruction by rodents or cats. If a book is shelved upside down, one is to turn the book right side up and kiss it (Tzvi Hirsch Koidonover, d. 1719, in Sefer Kav haYashar). One should not shame a holy book by placing it on a bench on which one is sitting , exposing one’s nakedness to it, or taking it into a bathroom.

Parallel to the treatment of holy texts as royalty are other rules dealing with how one treats books. De Vidas said that showing honor to one’s library includes placing books in a prominent place in one’s home, protecting them with heavy pieces of cloth, and using traps to protect the books from destruction by rodents or cats. If a book is shelved upside down, one is to turn the book right side up and kiss it (Tzvi Hirsch Koidonover, d. 1719, in Sefer Kav haYashar). One should not shame a holy book by placing it on a bench on which one is sitting , exposing one’s nakedness to it, or taking it into a bathroom.

What happens if a Sefer Torah falls to the ground? Many people believe that the person responsible should fast, along with any who saw the Torah fall. The origin of this custom, however, is fairly late (17th century), apparently popularized by the Polish authority R. Abraham Gombiner. Other rabbis have suggested alternatives, including giving money to tzedakah (social justice causes), buying a new Torah mantle, reciting psalms, or learning the laws related to the Sefer Torah. Ultimately, most rabbis will follow the practical advice of R. Hayyim Yosef David Azulai, who said that the “local rabbi should rule as he sees fit in order that they should be careful in the future, and everything [should be decided] according to the time and place.”

When Books Are Like People

One might argue that the only thing treated with greater sanctity than holy books in general and the Sefer Torah in specific is human life, but in some ways, books are even given a kind of humanity. It is not uncommon that great rabbinic authors “lose” their personal identity and become known as the authors of their books. For example, Yaakov ben Asher was known as the Ba’al haTurim after his work, the Arba’ah Turim (ba’al means “master of”), and Zerachiah haLevi, the author of Sefer Me’orot, became known as the Ba’al haMaor. In other cases, the authors simply became known by the titles of the books themselves. When one refers to the Hafetz Hayim, one must take care to indicate whether one is referring to the influential book on the ethics of language, or its author, Israel Meir haKohen.

Perhaps the most interesting way in which books become almost human is reflected in this comment by Jonah ben Elijah Landsofer:

Our sages of blessed memory warned and threatened that one should not teach law in front of one’s teacher (one should defer to one’s teacher); similarly, one should not teach law in front of one’s teacher when one’s teacher is a book [and] when the book is available to him to look up the law. Even if the matter is obvious to him, in any case, out of respect for the book, it is appropriate to open it up and to look up what is the law. For the letters themselves provide wisdom, and many times the law is made clearer from looking in the book than from just teaching from memory. Furthermore, when other scholars are present and the law is clear to them, one should not be embarrassed (to consult a book); to the contrary, this is how one shows honor to the Torah by clarifying the law to a point of certainty (Hanhagot Tzadikim, R. Yonah Landsofer 8:45).

Of course, Landsofer’s emphatic charge to check one’s sources is designed to maintain a level of professionalism in the administration of Jewish law, but it is clear from his language that in his mind, books do represent their authors and are therefore deserving of great respect as teachers in their own right. The fact that Landsofer was a scribe and a descendant of a long family of scribes might have had an influence on his attitude.

The ultimate sign of respect for books, however, is how they are treated when they wear out. Holy books, like the people who used them, are buried, usually sharing the grave with a deceased Torah scholar (following Talmud Megillah 26b). This serves both to honor the books and to prevent further degradation. In modern times, with the tremendous increase in the amount of printed material and photocopies of holy books, storage and/or burial have become quite difficult. Different authorities have suggested various responses, although most agree that a Sefer Torah as well as printed editions of biblical texts should still be buried, even if options are found for non-biblical texts and copies made for temporary use.

ark

Pronounced: ark, Origin: English, the place in the synagogue where the Torah scrolls are stored, also known as the aron kodesh, or holy cabinet.

Mishnah

Pronounced: MISH-nuh, Origin: Hebrew, code of Jewish law compiled in the first centuries of the Common Era. Together with the Gemara, it makes up the Talmud.

Sephardic

Pronounced: seh-FAR-dik, Origin: Hebrew, describing Jews descending from the Jews of Spain.

Talmud

Pronounced: TALL-mud, Origin: Hebrew, the set of teachings and commentaries on the Torah that form the basis for Jewish law. Comprised of the Mishnah and the Gemara, it contains the opinions of thousands of rabbis from different periods in Jewish history.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.

Yaakov

Pronounced: YAH-kove or YAH-ah-kove, Origin: Hebrew, Jacob, one of the Torah's three patriarchs.