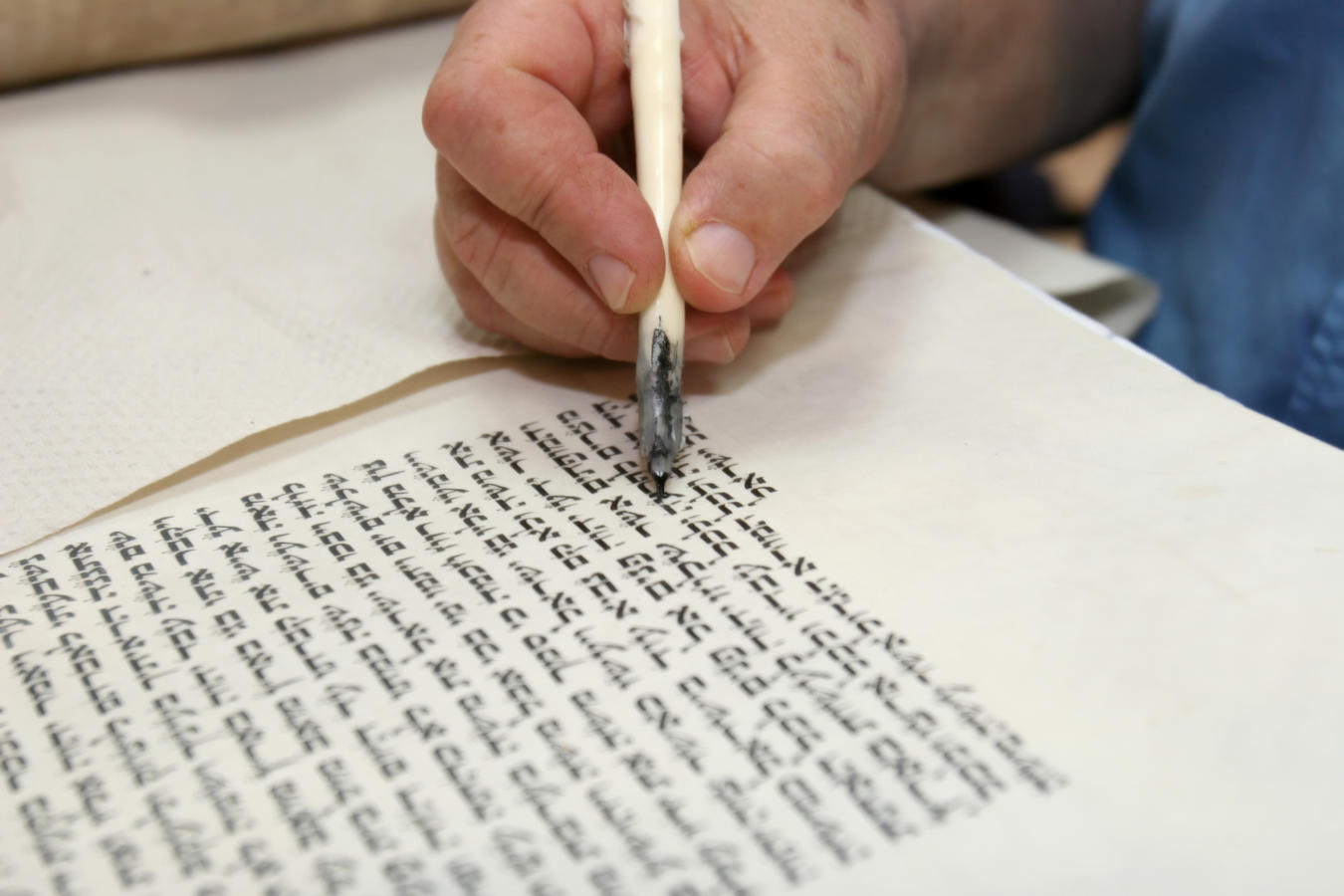

The last mitzvah in the Torah, as understood by the rabbis, is delivered to Moses and Joshua: “Therefore, write down this poem and teach it to the people of Israel; put it in their mouths, in order that this poem may be my witness against the people of Israel.” (Deuteronomy 31:19)

In the Talmud, the 3rd-4th-century sage Rava uses the quote to assert that every Jew is obligated to write their own Torah scroll (Sanhedrin 21b).

Nearly 1,000 years later, the commentator known as The Rosh had a new take on this tradition, in keeping with the customs of his time. At that point, Torah scrolls were already kept in synagogues’ arks, and were not used for studying. The Rosh argued that the commandment need not be understood literally, but instead could be applied to books that are written for individual Torah study.

In the 16th century, Rabbi Joseph Caro, author of the Shulchan Aruch, wrote that he was surprised by the Rosh’s conclusion. Surely he did not mean to exclude the writing of a Torah scroll, Karo argued, but rather he must have meant in addition to the writing of a scroll, one could write Mishnayot, compendia of oral law.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

After the invention of printing, some commentators continued the Rosh’s trend of interpreting the mitzvah in light of new customs and technology. According to the 18th-century commentator Rabbi Abraham Danzig, a Jew’s obligation was to own, and not necessarily write, sacred books for studying. As printed books became more readily available, the gap between the cost of writing a Torah scroll and printed Jewish sacred texts would only grow, and thus this mitzvah came to be understood as encouragement for studying Torah, as opposed to the more narrow understanding of writing one.

mitzvah

Pronounced: MITZ-vuh or meetz-VAH, Origin: Hebrew, commandment, also used to mean good deed.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.