The root of the Hebrew term used to refer to Jewish law, halakhah, means “go” or “walk.” Halakhah, then, is the “way” a Jew is directed to behave in every aspect of life, encompassing civil, criminal and religious law.

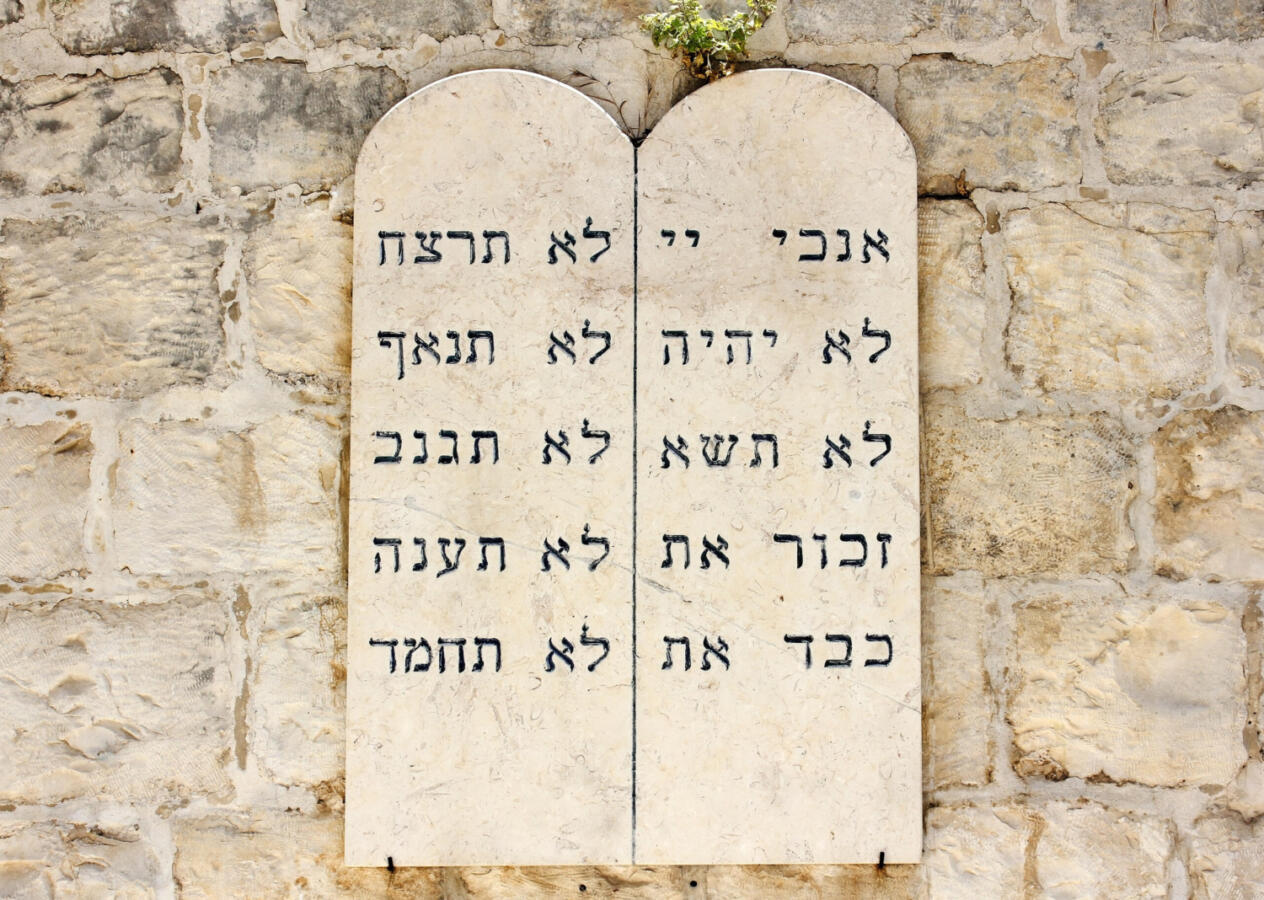

The foundation of Judaism is the Torah (the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, sometimes referred to as “the Five Books of Moses”). “Torah” means “instruction” or “teaching,” and like all teaching it requires interpretation and application. Jewish tradition teaches that Moses received the Torah from God at Mount Sinai. The Torah is replete with instructions, directives, statutes, laws, and rules. Most are directed to the Israelites, some to all humanity.

Writing and Talking

The words of the Torah constitute what the rabbinic tradition calls the Written Torah. However, beginning around 400 BCE, teachings emerged based in or connected to the Torah, but not literally evident in the text. This body of teaching is known as the Oral Torah, and rabbinic sources claim that it, too, was revealed at Sinai. Halakhah per se begins with this “Oral Torah.”

Some laws in the Torah required procedures for their observance that were not explicit. Sometimes conditions under which Jews were living were so different from earlier periods that the ancient rabbis simply enacted new rules in keeping with the laws of the Torah. This process of developing, interpreting, modifying and enacting rules of conduct is the how halakhah develops. The rabbis of classical talmudic Judaism developed a system of hermeneutic principles by which to interpret the words of the written Torah.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

As rabbinic teachings increased, it was necessary to commit them to writing, lest they be forgotten. Around the year 200 CE, the Mishnah, the earliest compendium of Jewish law, appeared. It became the curriculum of rabbinic instruction. In approximately 425 CE, the interpretive traditions of the rabbis of the Land of Israel were compiled, forming the Talmud Yerushalmi (Palestinian Talmud).

Another Talmud, the “Bavli” (Babylonian Talmud), was compiled in the Persian Empire a century later. It presents digests of the various teachings of many generations of rabbis on issues of law and other subjects. Although it frequently fails to specify which cited opinion is authoritative, it nevertheless became the universally accepted arbiter of halakhah and the subject of many extensive commentaries.

Leaders and Researchers

In every age, outstanding Jewish teachers and thinkers emerged who became the rabbinic leaders of their communities. Individuals, including other rabbis, would send them questions about the proper observance of Judaism or matters of Jewish thought. This body of questions and responses (teshuvot, or responsa), preserved through the ages, is also an important source of halakhah.

In the Middle Ages, the body of Jewish legal writing was so voluminous that great scholarly acumen was required to be able to determine exactly what the halakhah was on many points. Compendia of Jewish law were written to summarize the debate and render a decision. One of the most complete and influential of these, Maimonides‘ Mishneh Torah, was compiled in the 11th century. The sixteenth-century Sephardic rabbi Joseph Caro developed a handbook of halakhah, the Shulhan Arukh (“Prepared Table”). Supplemented by the comments of Rabbi Moses Isserles, the leading Polish rabbi of the time, the Shulhan Arukh became the worldwide standard of halakhah, authoritative (even if not the final authority) even now in the eyes of observant Jews everywhere.

Historically, in Jewish law, a majority view prevailed. While the majority opinion usually became the accepted practice, in certain circumstances later rabbis could rely on a minority view in deciding a difficult matter. By the high Middle Ages, most Jewish communities each recognized one rabbi as the arbiter of Jewish law in that community.

Modernity and Halakhah

This system collapsed with the onset of modernity in the 18th century, particularly in western Europe. Rabbis emerged who wanted to “reform” Judaism. They rejected both some of the teachings and the authority of earlier rabbis in many matters of halakhah.

Today, spiritual descendants of both traditionalists and reformers interpret Jewish law according to their respective principles for their communities. Many Jews reject the notion of Jewish law as binding, regarding halakhah as spiritual guidance for Jewish living. The approach to halakhah is the central factor differentiating Jewish religious movements today. Secular Israeli jurisprudence treats halakhah as a valid and valued source of precedent.

Sephardic

Pronounced: seh-FAR-dik, Origin: Hebrew, describing Jews descending from the Jews of Spain.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.

halacha

Pronounced: hah-lah-KHAH or huh-LUKH-uh, Origin: Hebrew, Jewish law.