Many Jews have read The Diary of Anne Frank, but much fewer have heard of the extraordinarily gifted Etty Hillesum, a Dutch Jew who also wrote diaries during the Holocaust and perished in Auschwitz.

Etty Hillesum’s diaries and letters were first published in English in 1983. Her writing has been embraced across the religious spectrum; her universal messages of love of humanity and God, and of acceptance of suffering, have particularly resonated with Christian and Buddhist readers. Yet Hillesum has yet to fully enter the canon of modern Jewish literature, and deserves to be counted among the great Jewish philosophers, thinkers and mystics of the modern era. Especially during particularly difficult moments, Hillesum’s writing can serve as a source of spiritual resilience for the Jewish community. In her own words, she wanted to be “a balm for all wounds.”

Despite all the suffering and injustice I cannot hate others. All the appalling things that happen are no mysterious threat from afar, but arise from fellow beings that are very close to us.

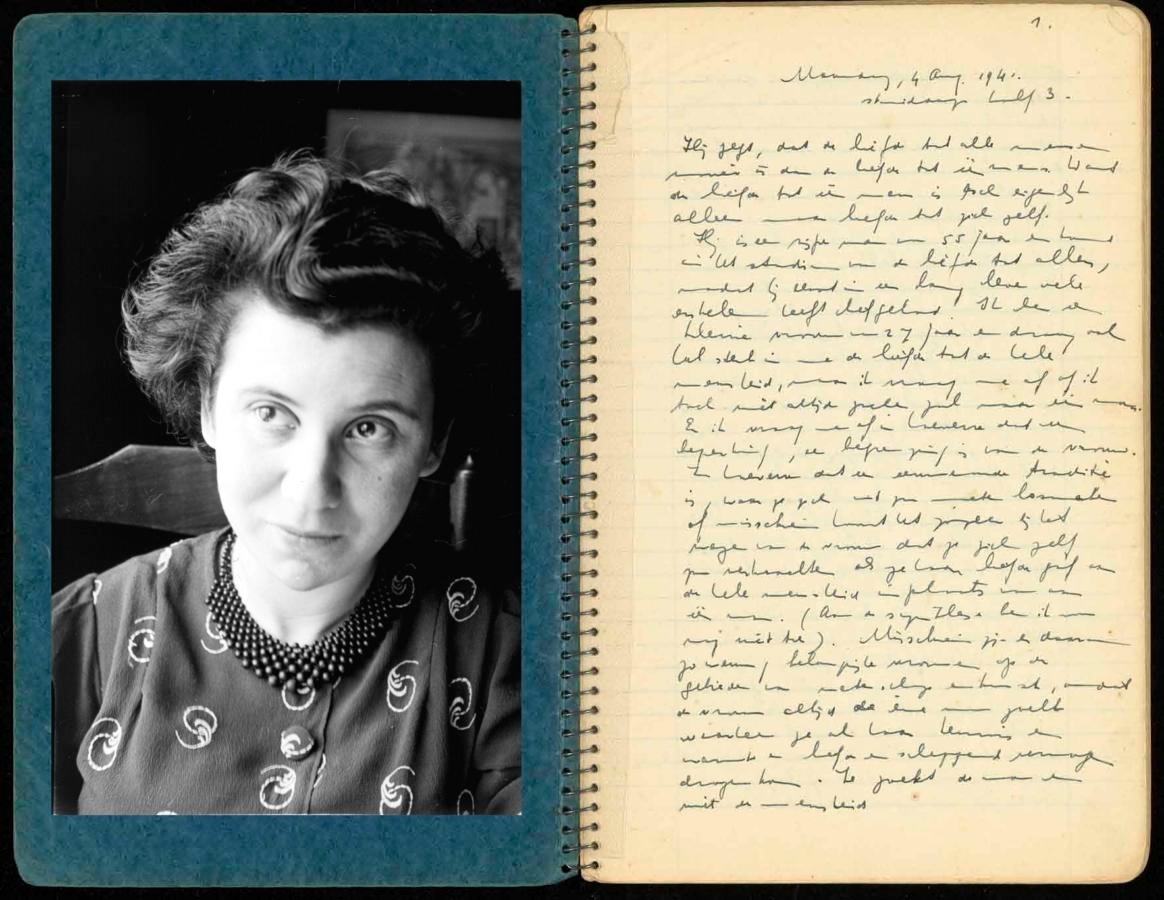

Hillesum was born in 1914 in Middleburg, the Netherlands, to Levi (Louis) Hillesum and Riva Bernstein. The oldest of three children, she moved to Amsterdam in 1932 to study law and Slavic languages. In March 1941, at the age of 27, she began keeping a diary, at the suggestion of her psychoanalyst and (later) lover Julius Spier. We learn from her diary that her home life was emotionally tumultuous, and she suffered from depression. The diary traces her psychological development and deepening spiritual awareness. It reveals a woman who aspired to be a writer — who studied Dostoyevsky, Rilke, the Bible and St. Augustine with fervor — and who found a “refuge” in words.

One of the most astonishing aspects of Hillesum’s writing is her ability to witness the horrors around her with clear-eyed stoicism, strength and grace. The themes of acceptance of suffering and refusal to hate the enemy recur in her writing. Hillesum worked in an administrative capacity for the Judenrat, the Nazi-imposed Jewish Council, and had to interact with Nazis. Yet even in her assessment of the oppressor, she is able to recognize their humanity.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Hillesum believed that no one is truly evil deep down. And while she did not look away from the dark reality closing in on Dutch Jewry, she still asserted, “Despite all the suffering and injustice I cannot hate others. All the appalling things that happen are no mysterious threat from afar, but arise from fellow beings that are very close to us.”

Instead of focusing her energies on hatred, Hillesum attuned to her inner life. This cultivation of spiritual self-awareness was not mere navel-gazing. She didn’t ignore the reality of history unfolding around her, but dug deep into her soul to discover a profound source of strength: “One moment it is Hitler, the next it is Ivan the Terrible; one moment it is Inquisition and the next war, pestilence, earthquake, or famine. Ultimately what matters most is to bear the pain, to cope with it, and to keep a small corner of one’s soul unsullied, come what may.”

Hillesum’s love of humanity was not abstract; she embodied that belief. Though she had multiple opportunities to save herself, she instead chose to go to the transit camp in Westerbork to work in the hospital and care for her fellow Jews, sharing their ultimate fate. In her letters from Westerbork she was honest about the inhumane conditions, but insisted, “I find life beautiful, and I feel free. The sky within me is as wide as the one stretching above my head. I believe in God and I believe in man, and I say so without embarrassment.”

While in practice Hillesum was a secular Jew, her singular and pure devotion to God places her among the classical Jewish mystics and Hasidic thinkers. Though it is not clear that she studied traditional Jewish literature beyond the Bible, Hillesum’s writing often reads like the outpourings of an iconoclastic Hasidic rebbe. For example, a statement like “If … you manage to come to grips with your inner sources, with God, in short, and if only you make certain that your path to God is unblocked … then you can keep renewing yourself at these inner sources and need never again be afraid of wasting your strength” is reminiscent of Rabbi Nachman of Breslov. And like Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Kotzk, who said, “Where is God to be found? In the place where He is given entry,” Hillesum’s relationship with God was existentialist, rooted in human experience: “When I pray, I never pray for myself. Always for others, or else I hold a silly, naïve, or deadly serious dialogue with what is deepest inside me, which for the sake of convenience I call God.” And like Martin Buber and Abraham Joshua Heschel, Hillesum believed that love of God is essentially intertwined with love of humanity.

Perhaps the reason Hillesum has yet to be canonized as a great Jewish religious thinker is that she was not an observant Jew. Her conception of God, while influenced by many different religious and literary sources, was personal and free of the strictures of religion. She rarely cites Jewish sources, except the Bible. She also preferred to be non-monogamous; she felt her love for humanity was so great that she couldn’t love just one person. She also did not have a desire to have children. From a mainstream Jewish perspective this orientation would be considered radical (especially for a woman in the 1940s).

Another reason she may not have been fully embraced as a Jewish thinker was her belief in accepting the horrors of the Holocaust — what might be seen as a Buddhist kind of response. Some people view her acceptance of suffering as a form of resignation or even escapism. But that misses just how profound a form of resilience she discovered. The fact that Hillesum maintained a belief in God and in the ultimate goodness of humanity, and lived that belief by volunteering to care for fellows Jews in the concentration camp, reveals the most powerful way of fighting of evil: through love.

Modern Jews can, and should, claim Hillesum as part of their Jewish literary heritage. Her life and writing testify to the power of the human soul to face the darkest of times. Her diaries and letters teach us that we all contain a deep well of strength that can help us respond to the worst suffering. Spiritual resilience is possible, Hillesum asserts, when we tend to our inner lives, attest to the beauty of the world, and care for others: “What matters is not whether we preserve our lives at any cost, but how we preserve them.”