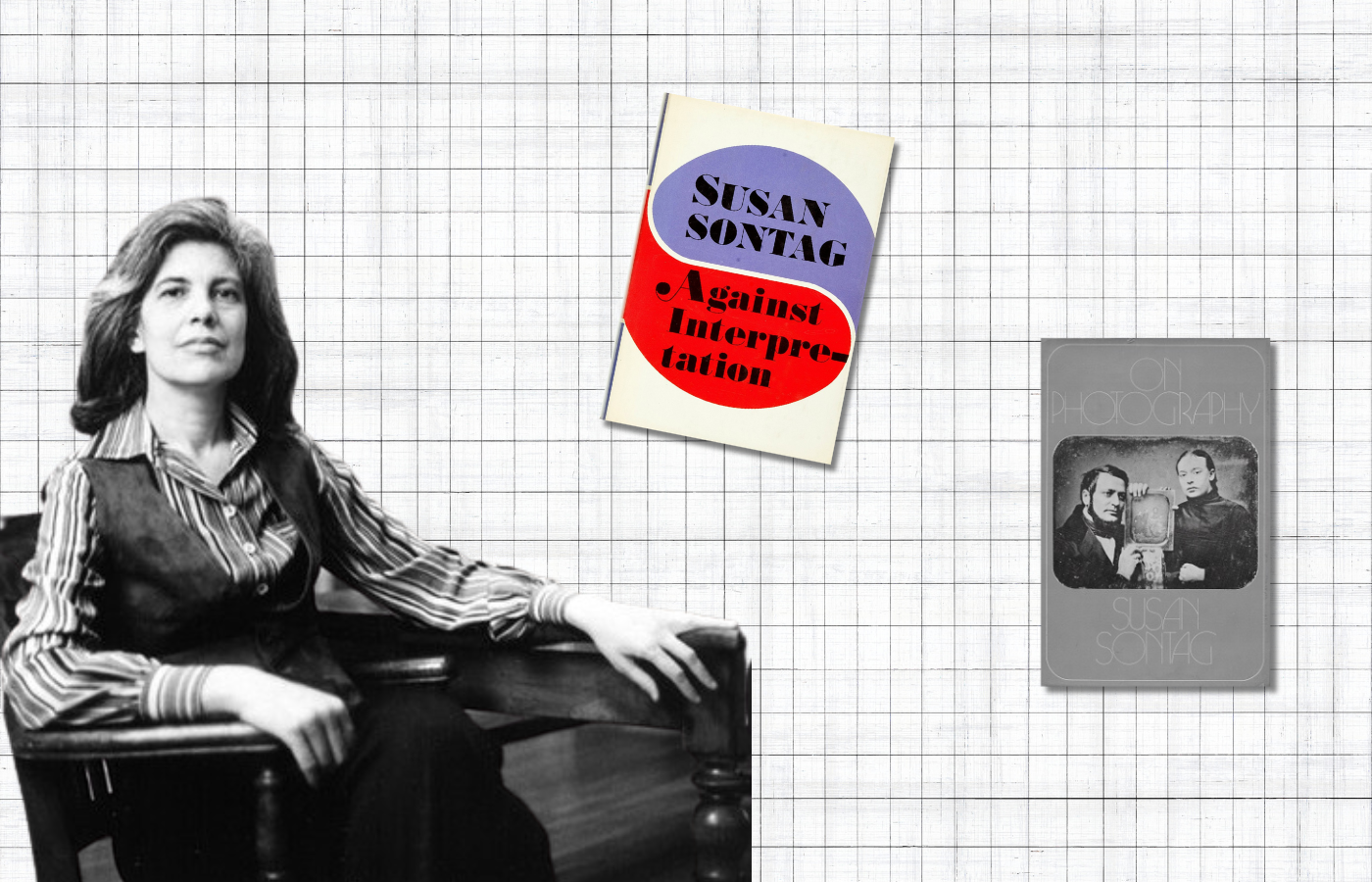

Susan Sontag was born in New York City in 1933 and raised mostly in Los Angeles. She showed a voracious interest in literature at a young age and graduated from high school at the age of fifteen. She married while in college and had one son. After several years studying in Boston, England, and France, she settled in New York, where she had a highly successful literary career. Her essay “Notes on Camp,” about the quirky, high-low “camp” aesthetic, earned her early fame. Her book Against Interpretation (1966) further solidified her position as a public intellectual. She went on to write many books of essays, novels, and plays. Some of her most famous works deal with AIDS and illness, photography, aesthetics, and morality. Sontag was first diagnosed with cancer in 1975; after multiple recurrences, she ultimately died of leukemia in 2004.

Impact

When her essays first began appearing on the American critical scene in the early 1960s, Susan Sontag was heralded by many as the voice—and the face—of the Zeitgeist. Advocating a “new sensibility” that was “defiantly pluralistic,” as she announced in her groundbreaking collection of essays Against Interpretation (1966), Sontag became simultaneously an intellectual of consequence and a popular icon, publishing everywhere from Partisan Review to Playboy and appearing on the covers of Vanity Fair and the New York Times Magazine. She became for many a cultural symbol, the image of the female intellectual; she herself would joke that she was best known for the white streak in her dark hair, rather than for anything she had written. In her work, she rejected the traditional project of art interpretation as reactionary and stifling and called instead for a new, more sensual experience of the aesthetic world: “an act of comprehension accompanied by voluptuousness” (Against Interpretation, 29). Challenging what she saw as “established distinctions within the world of culture itself—that between form and content, the frivolous and the serious, and… ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture,” Sontag stood as a champion of the avant-garde and visual arts in particular (Against Interpretation, 297).

As the only woman among the 1960s world of New York Jewish intellectuals, Sontag was both venerated and villainized, depicted as either a counter-cultural hero or a posturing pop celebrity. In a 1968 essay in Commentary, Irving Howe saw her as the “publicist” for a young generation of critics that was making its presence felt “like a spreading blot of anti-intellectualism.” Focusing on the woman rather than the work, other critics dubbed her “Miss Camp” (after her famous essay “Notes on Camp”) and “The Dark Lady of American Letters” (a moniker borrowed from Mary McCarthy). Indeed, in his 1967 book Making It, Norman Podhoretz snidely attributed her popularity to her gender and to the fact that she was “clever, learned, good-looking, capable of writing family-type criticism as well as fiction with a strong taste of naughtiness.” While Sontag’s public image later shifted from that of sixties radical to nineties neo-conservative, neither representation accounts for either the complexity of her views or the significance of her contribution to contemporary cultural debates—particularly on topics such as photography, illness, and the representation of suffering.

Sontag was the subject of intense media scrutiny throughout her career, despite her own consistent rejection of the biographical as a means of understanding a work. “I don’t want to return to my origins,” she told Jonathan Cott in an interview. “I think of myself as self-created—that’s my working illusion.” Her distrust of the potentially reductive nature of personal, biographical criticism was magnified by her insistence that she herself did not “have anything to go back to.”

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Early life and career

Susan Sontag was born on January 16, 1933, in New York City, the older of Jack and Mildred (Jacobson) Rosenblatt’s two daughters. Her early years were spent with her grandparents in New York while her parents ran a fur export business in China. When she was five, her father died of tuberculosis and her mother returned from China. A year later, mother and daughters moved to Tucson, Arizona, in an effort to relieve Susan’s developing asthma. In 1945, Mildred Rosenblatt married Army Air Corps captain Nathan Sontag, the daughters assumed their stepfather’s last name, and the family left Arizona for a suburb of Los Angeles. Although her parents were Jewish, Sontag did not have a religious upbringing, and she claims not to have entered a synagogue until her mid-twenties.

The one autobiographical essay that Sontag published during her lifetime, “Pilgrimage,” depicts the writer’s long-standing sense of rootlessness and fragmentation as “the resident alien” in a “facsimile of family life.” It also expresses her feeling of intellectual isolation and her fear of “drowning in drivel” in suburban America. “Literature-intoxicated” from a very young age, she read the European modernists to escape “that long prison sentence, my childhood” and to achieve “the triumphs of being not myself.” Many of these issues—the fierce individualism of the intellect, the pleasure and nourishment to be derived from knowledge, and the question of what it means to be modern—became central themes in Sontag’s fiction and essays. These concerns are also on display in her posthumously published journals, which record her thoughts, beginning at age fourteen. The journals display a young writer brimming with both precocious intellect and recurrent self-questioning.

At age fifteen, Sontag discovered literary magazines at a nearby newsstand, and she described her excitement in an interview with Roger Copeland by explaining that “from then on my dream was to grow up, move to New York, and write for Partisan Review.” She achieved this dream in 1961, after twelve years in the academic world. Having graduated from high school at age fifteen, Sontag spent one semester at the University of California at Berkeley before transferring to the University of Chicago for the remainder of her college study. There she met Philip Rieff, a sociology lecturer, while auditing a graduate class on Freud. They married ten days later, when Sontag was seventeen and Rieff twenty-eight. Their only son, David, who would later be for some time her editor at Farrar, Straus and Giroux, was born in 1952. That same year, Sontag entered Harvard as a graduate student in English and philosophy. After receiving master’s degrees in both fields (1954 and 1955, respectively), Sontag left her husband and son and spent two years studying at Oxford and the Sorbonne, although she did not complete a dissertation at either institution.

Shortly after her return to the United States in 1959, she divorced Rieff and moved to New York City, with “seventy dollars, two suitcases and a seven-year-old [her son].” As she explained in the interview with Jonathan Cott: “I did have the idea that I’d like to have several lives, and it’s very hard to have several lives and then have a husband. … [S]omewhere along the line, one has to choose between the Life and the Project.” In the final decade and a half of her life, Sontag had a relationship with her the photographer Annie Leibovitz, with whom she would sometimes collaborate artistically.

Career

In New York, Sontag began establishing herself as an independent writer while teaching philosophy in temporary positions at Sarah Lawrence, City College, and Columbia University and working briefly as an editor at Commentary. She published twenty-six essays between 1962 and 1965, as well as an experimental novel, The Benefactor, in 1963. Although best known for her nonfiction, Sontag worked in many creative genres. The 1960s and 1970s saw the production of a second novel, Death Kit (1967), a collection of short stories, I, Etcetera (1978), and the script and direction of three experimental films: Duet for Cannibals (1969), Brother Carl (1971), and Promised Lands (1974). Promised Lands, a documentary on Israel’s Yom Kippur War, was the only one of Sontag’s works that dealt explicitly with Jewish issues.

Sontag’s career-long series of essays—or “case studies,” as she called them in Against Interpretation—revealed an expansive and democratic definition of art, encompassing such diverse subjects as photography, illness, fascist aesthetics, pornography, and the Vietnam War. A self-described intellectual generalist, Sontag explained in an interview with Roger Copeland that her overarching project was to “delineate the modern sensibility from as many angles as possible.” Sontag’s writing was notable for its style, often aphoristic in character. Her essays ranged freely from high modernism to mass culture, from European to American artistic figures, from the aesthetics of silence to the contemporary media proliferation of images and noise. Her career as a writer was characterized by the tension between such oppositions: “Everything I’ve written—and done,” she explained, “has had to be wrested from the sense of complexity. This, yes. But also that. It’s not really disagreement, it’s more like turning a prism—to see something from another point of view.”

In both her fiction and her critical essays, Sontag told Copeland, she used such disjunctive forms of writing as “collage, assemblage, and inventory” to demonstrate her thesis that “form is a kind of content and content an aspect of form.” Insisting that interpretation is “the revenge of the intellect against the world,” Against Interpretation, her first collection of essays, sought to subvert both the style and the subject matter of traditional critical inquiry. The function of criticism should be to help us experience art more fully, she explained, “to show how it is what it is, even that it is what it is, rather than to show what it means.” Against Interpretation introduced an American audience to lesser-known European figures such as Georg Lukács, Simone Weil, and Claude Lévi-Strauss. It also explored the irreverent playfulness and self-conscious artificiality of an underground camp aesthetic.

Styles of Radical Will (1969) advanced Sontag’s aesthetic argument by looking closely at pornography, theater, and film, and by examining the impact of self-consciousness on the modern art and philosophy of E. M. Cioran, Ingmar Bergman, and Jean-Luc Godard. But the collection suggested a political as well as an aesthetic mode of transforming consciousness. The essay “Trip to Hanoi,” originally published in 1968 as a separate book, was Sontag’s candid response to her trip to North Vietnam as she grappled with the limits of her own culturally formed perceptions. Under the Sign of Saturn (1980), which comprised seven essays of the 1970s, combined personal reflections on Paul Goodman and Roland Barthes with sustained analyses of Walter Benjamin, Antonin Artaud, and Elias Canetti. It also contained the well-known piece “Fascinating Fascism,” in which Sontag used Leni Riefenstahl’s Nazi propaganda films to discuss the ways in which history becomes theater.

Sontag’s award-winning volume On Photography (1977) analyzed how photographic images have changed our ways of looking at the world. Resistant to the acquisitive nature of photography and its consequent leveling of meaning, Sontag here displayed a growing suspicion of the “sublime neutrality” of art that she had so heralded in Against Interpretation. Although hopeful about the value of photography when it awakens the conscience of the audience, she was also concerned about its potentially predatory nature, explaining that “[t]o photograph people is to violate them.” Like On Photography, Illness as Metaphor (1978) broke new critical ground by examining the significance of a common cultural phenomenon, specifically regarding pain and suffering: in this case, the discursive representation of disease. Growing out of Sontag’s own diagnosis of breast cancer in 1975, the book sought to expose the fantasies and fears that are masked by the vocabulary of illness. In 1989, she elaborated on this theme in AIDS and Its Metaphors, which was received with some controversy. Many in the gay community criticized her efforts to disentangle the cultural metaphors of AIDS from its politics.

Sontag also focused her efforts on fiction and theater in these years. Unguided Tour, the film version of an earlier short story, appeared in 1983. In 1985, she directed the premier production of Milan Kundera’s play Jacques and His Master. Her own play, Alice in Bed, premiered in Bonn, Germany, in 1991 and was published in 1993. That same year, she traveled with her partner, photographer Annie Leibovitz to act, in her words, as a “star witness” during the Bosnian War. While there Sontag directed Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot in war-besieged Sarajevo. Twenty-five years after the publication of her previous novel, Sontag’s critically acclaimed The Volcano Lover (1992) appeared, bringing together concerns that long animated her writing: the relationship between style and form, the moral pleasure—and service—of art, and the psychology of collecting. A historical novel with a self-consciously modern narrator, The Volcano Lover was a revisionary retelling of the eighteenth-century love affair between Lady Emma Hamilton and Lord Horatio Nelson that moved away from the abstraction of Sontag’s earlier fiction while still remaining a novel of ideas. Sontag’s final novel, In America (2000), which won the National Book Award for Fiction, was also set in the past; based on the life of a nineteenth-century Polish performer who immigrated to America with the dream of establishing a utopian community, the novel relied on the language of theater and acting in order to consider the thematic possibilities of re-inventing both the individual and the nation.

Sontag continued to write essays about photography toward the end of her life. She returned to the topic, first with an essay written to accompany a series of women’s portraits by Leibovitz (published as Women in 1999; an exhibition of the photographs then went on national tour), and then with Regarding the Pain of Others (2003), which discussed the ramifications of the near ubiquity of images of war. Her final work published during her lifetime was Regarding the Torture of Others (May 23, 2004), an essay in the New York Times Magazine about American soldiers’ torture of Iraqi prisoners in Abu Ghraib. Building on her body of work, she explored the moral ramifications of the seemingly banal, widely circulated, cell phone-captured photographs of this torture.

Legacy

Sontag, who had suffered from cancer intermittently for thirty years (she had been told after her original diagnosis in 1975 that she had a ten percent chance of surviving for two years), died of complications of acute myelogenous leukemia on December 28, 2004, two weeks shy of her seventy-second birthday. Leibovitz photographed Sontag’s final days, as she was caring for her, and published images of Sontag on her deathbed in the book A Photographer’s Life:1990-2005 (2006), to some controversy. This would be but the first in a series of posthumous biographical and autobiographical works about Sontag. These include her journals, edited by her son and published in two volumes (Reborn covers 1947-1963 and As Consciousness is Harnessed to Flesh covers 1964-1980), a play, Sontag: Reborn (2013), based on the journals, an authorized biography, and a documentary film. Sontag has continued to inspire reexamination in as many forms as she herself engaged in.

Reprinted from the Shalvi/Hyman Encyclopedia of Jewish Women with permission of the author and the Jewish Women’s Archive.