We venerated my great aunt. She was among the family’s matriarchs about whom one reliably said, “Even though she had been a poor immigrant, she always shared what little she had with new refugees.” My cousins and I were all expected to name children after her, and we did.

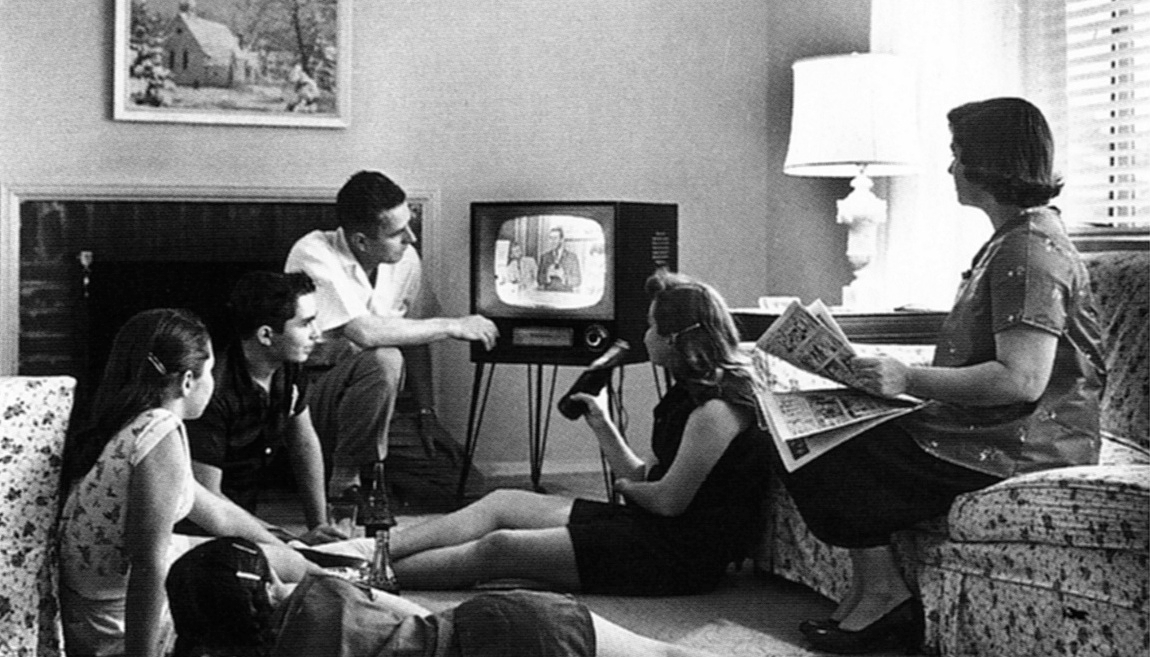

When we used to visit the great aunt in her small apartment, her small black and white television was on all the time and she talked back to it. Not just cheering and booing at the Yankees — everyone did that — but yelling at the characters on shows or old movies, telling them what to do. “Don’t go! Watch out!” It was as if she believed the characters, like her children, should hear her and take her advice. For all beings, apparently including those on TV, she was in a state of perpetual vigilance. A child of some technological sophistication, I suspected that the great aunt could have let down her guard when it came to TV. While all of us children at home believed the Romper Room teacher could see us at home in TV-land when she looked through her magic mirror, I very much doubted the characters on our great aunt’s TV could hear her.

I am my great aunt’s age now, maybe even older. How old could she have been back then? Sixty, sixty-five? (Remember: They didn’t do yoga in those days.) While I neither talk to characters in Netflix shows nor see myself as responsible for them, when I study Torah and commentaries on my little black and white iPad, I steadily talk back to the biblical figures I encounter and offer advice.

This week, I am busy talking to Jacob as we get to the part of the Joseph story where the brothers are reconciling. Joseph, now a powerful man in Pharaoh’s court, is proclaiming that his father Jacob and all of his family must immediately leave Canaan where there is a famine and journey to Egypt. There Joseph will provide them with everything they need, even Pharaoh’s patronage. Pharaoh, hearing of the offer, presses the family to come immediately; don’t even bother downsizing first: “Never mind your belongings; for the best of the land of Egypt shall be yours.” Jacob — astonished to hear his son Joseph is still alive — is ready to jump on the first camel.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Channeling my great aunt, I am shouting at my iPad to Jacob, “Don’t go!”

Why am I telling Jacob this? Why do I caution him to stay put in Canaan, even though I know that if he stays he will not see his son Joseph again, get to spend quality time with his grandchildren Ephraim and Manasseh, and — perhaps most importantly — find relief from the famine?

Fast-forwarding just a few generations, there will be a new pharaoh in Egypt who won’t know of Joseph and how he saved the Egyptians. The Israelites, who by that time will have become numerous and successful, will be seen as a threat, and therefore enslaved and oppressed. True enough, the Israelite slaves will eventually be freed, redeemed by God, and will meander homeward. And there is the great consolation prize: Because the narrative of slavery and divine redemption has unfolded, the Jewish people inherit one of their most precious legacies: To care for the stranger. “You shall not oppress a stranger, since you yourselves know the feelings of a stranger, for you were also strangers in the land of Egypt.” (Exodus 23:9)

But what if … What if the central narrative of the Jewish people had been otherwise? What if we had skipped the trauma and agony of slavery? Could we have become a people whose core attributes are compassion and sensitivity?

Jacob apparently doesn’t need to hear my warnings — he doubts moving forward himself. After he and his entourage set out for Egypt, Jacob pauses in Be’er Sheva to examine his misgivings. Be’er Sheva was more than a rest stop for the weary on the biblical map. There, Abraham and Isaac had dug wells and struck peace treaties with neighboring kings. It’s where Jacob had long ago dreamed of a ladder leading to heaven. It was where other pilgrims on sacred journeys might also have stopped with the purpose of incubating a dream. The practice was common in ancient cultures: Following purification, one made an offering, posed a question and went to sleep, hoping for a dream that would solve a problem, clarify what direction to take or what decision to make. On his way to Egypt, it works again for Jacob, whom God tells: “Fear not … I myself will go down with you to Egypt and I myself will also bring you back” (Genesis 46:3-4).

And so, once again — yes, I have tried to intervene before — my voice of caution goes unheard. Jacob sets out, and the Jewish story unfolds. In my great aunt’s honor, however, I have no choice but to remain vigilant, and next year, when there’s a repeat of the “Jacob Goes Down to Egypt” episode, I may try to intervene once again.

This article initially appeared in My Jewish Learning’s Shabbat newsletter Recharge on Dec. 23, 2023. To sign up to receive Recharge each week in your inbox, click here.