The land that is now Ukraine made up much of the Pale of Settlement, where Jews in the tsarist empire were restricted to live from the late 19th century until the Bolshevik Revolution. In this vast territory, Hasidism was born and traditional yeshivas flourished. But Ukraine also saw the rise of a vibrant secular Jewish literature. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Jewish writers in Hebrew, Yiddish, Russian and Ukrainian presented the Jewish condition in Ukraine and were increasingly in dialogue with their non-Jewish neighbors. These writers, remembered in Ukraine among contemporary Jewish and non-Jewish writers alike, wrote about the traumas and hopes of their own communities and their work can serve as a guide to the ongoing conflicts between tradition and modernity, empire and sovereignty.

No one has summed up the secular Jewish condition quite like Isaac Babel, who described fantastical Jewish gangsters in his Odessa stories at a time when the Bolshevik revolution had turned the world upside down, ended the tsarist empire and abolished the Pale of Settlement. For Babel, writing in the early 1920s, anything was possible, from seducing Russian women to joining a Cossack Red Army regiment on horseback as a war correspondent (as Babel did in 1920). In his 1924 Odessa Stories, he wrote:

OK look – forget for a minute that you have glasses on your nose and autumn in your heart. Stop rioting behind your desk and stammering in public. Imagine for a moment that you’re rioting in public and stammering on paper. You’re a tiger, you’re a lion, you’re a cat. You can spend a night with a Russian woman, and the Russian woman will be satisfied.

Babel grew up in Odessa, a cosmopolitan milieu where secular Jewish literature in Russian, Hebrew, and Yiddish flourished. With its mix of cultures, the city was a microcosm of Eastern Europe. As in the broader Ukrainian territory, the city reflected the diversity of many overlapping empires. The groups that coexisted there didn’t always live peacefully, but they colored and changed each other’s narratives.

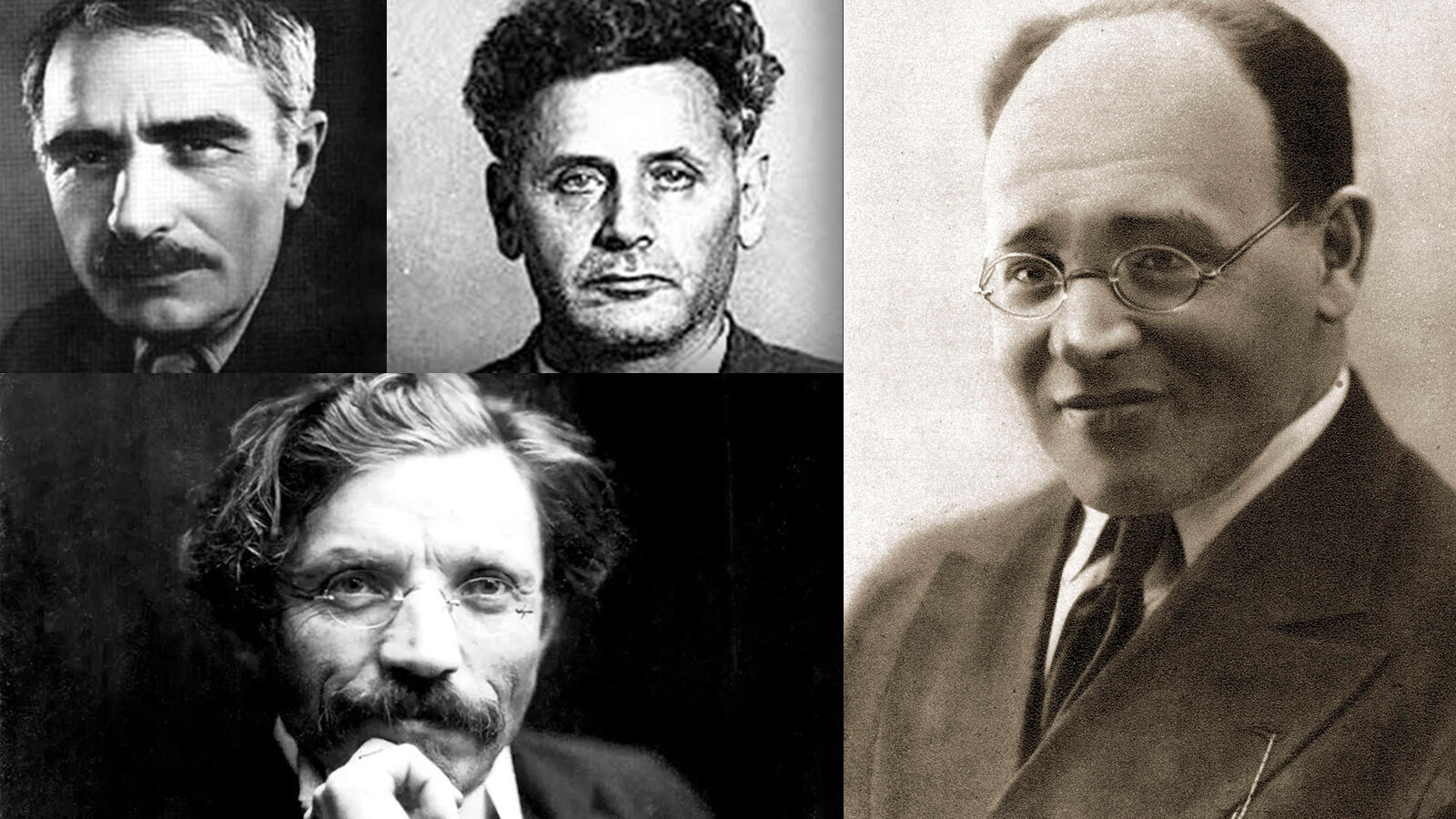

Jewish writers in the 19th century wrote stories they hoped might surreptitiously modernize their readership. They filled their fiction with cautionary tales of Jewish communities that were too insular or too easily manipulated by religious leaders. Israel Aksenfeld (1787-1866), who wrote the Yiddish novel The Headband in the 1840s, described the education of a young enlightener. In Tales of Benjamin the Third, Sholem Abramovich (1836-1917) tells of a Jewish Don Quixote who sets out to reach the land of Israel, but mistakes the ordinary Ukrainian landscape for the biblical places he longs to visit. And in The Bewitched Tailor (1901), Sholem Rabinovich (better known as Sholem Aleichem) writes of a Jew who fails to navigate the world beyond his shtetl. The story is funny, but it’s also deadly serious: Sholem Aleichem was using the nascent genre of secular Yiddish literature to teach his readers to educate themselves about the world.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

All these writers addressed a Jewish audience they hoped to convince to reform, or even abandon, the superstitions and insular hierarchy associated with shtetl life. In the process, they borrowed liberally from Hasidic tales and Russian and Ukrainian comic fiction.

By the turn of the 20th century, Yiddish literature took a darker turn. Jewish modernism spread in part due to the violence of the period. The pogroms, which had been the subject of some folk poems in the 1880s, inspired modern manifestations of medieval lamentations. Among the first modernist Jewish poems was Chaim Nachman Bialik’s Hebrew poem In the City of Slaughter (B’ir Haharegah). In the wake of a 1903 pogrom in Kishinev, Bialik visited the city (today the capital of Moldova), and his poem includes graphic descriptions of human casualties. Like other poems of the period, Bialik’s work helped the modernizing East European Jewish community make sense of the catastrophe. In the City of Slaughter was occasionally recited alongside, or in place of, prayers.

The Jewish community of Ukraine would experience more violence with World War I and the Russo-Polish war of 1918-1920, which brought waves of pogroms that killed thousands. Much of the secular Jewish literature that followed mourned the loss of life and the destruction of shtetl culture. “I’ve built a new ark for you,” Peretz Markish wrote in his long poem Di Kupe (The Mound), “in the middle of the marketplace/a black mound.” Dovid Hofshteyn’s book Troyer (Sadness), published in 1922 with illustrations by Marc Chagall, mourns the wartime loss of Jewish shtetls. Both these poets were members of the Kultur-lige, a secular Yiddish artistic organization formed in Kyiv in 1918, during Ukraine’s brief period of independence before being incorporated into the nascent Soviet Union. The Ukrainian branch of the Kultur-lige would eventually be rebranded as a Soviet publishing house.

Many of the modernists active in the Kultur-lige became central figures in Soviet Ukrainian literature. In the 1920s, Kharkiv, the first capital of Soviet Ukraine, was an important center of Jewish publishing. Two Soviet Yiddish literary journals based there, Prolit (a playful combination of “proletarian” and “literature”) and Royte Velt (Red World), published Soviet Yiddish writers, Soviet sympathizers from abroad, and Yiddish translations of works in other languages. These journals published an eclectic cross-section of Yiddish writers, from the poet Khane Levin, who wrote of her experience as a woman in the Red Army and the building of Soviet Jewish farming communities in Crimea, to the fiction writer Der Nister (pseudonym of Pinchas Kahanovich). The 1930s also saw the publication of remarkable works of Soviet Yiddish fiction about Ukraine. Der Nister, who lived in Kharkiv in the 1920s, wrote a two-volume historical novel, The Family Mashber, about a family from a Ukrainian shtetl. Dovid Bergelson published By the Dnieper in 1932, which describes a Ukrainian Jew who rejects his bourgeois family in favor of communism.

In the 1930s, Stalin was rapidly consolidating power and writers met increasing strictures on what they were able to safely publish. Many turned to translation, rendering canonical texts from other languages into Yiddish. Dovid Hofshteyn translated several volumes of poetry and prose by the Ukrainian poet Taras Shevchenko. Moyshe Khashchivatsky and Itsik Fefer translated Ukrainian classics and modernist writers into Yiddish. Stalin’s terror led to the arrests of many significant Jewish literary voices, including Der Nister, who was arrested and died in a gulag in 1950. Bergelson, Markish, Hofshteyn and Fefer were among those executed on the “Night of the Murdered Poets” in August 1952. Significant writers in non-Jewish languages also perished in the purge, including Isaac Babel, who was executed in 1940.

Along with Stalin’s increasing paranoia about ethnic minorities, the loss of most of the world’s Yiddish-speaking population in the Holocaust marginalized the status of Yiddish in the Soviet Union. After World War II, most surviving Jewish writers from Ukraine published in Russian. Significant voices included Ilya Ehrenburg and Dovid Grossman. But some writers, like Elsa Troyanker and Leonid Pervomaisky, wrote in Ukrainian, opting for what Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern has termed “the anti-imperial choice.”

Jewish writers of the past continue to influence contemporary literature in Ukraine. The Odessa poet Boris Khersonsky has written of the need to move beyond Soviet icons of internationalism like Babel to find new forms for post-Soviet Ukrainian writing. Younger writers have integrated Jewish history into Ukraine’s multiethnic past. The poet Iya Kiva has described her mixed Jewish and Ukrainian origins and the suffering of ancestors in both the Holocaust and the Ukrainian famine. The Ukrainian-born poet Alex Averbukh has incorporated Ukrainian and Hebrew into his Russian-language poetry. In 2017, the non-Jewish poet Marianna Kiyanovska published a long cycle of poems in Ukrainian, animating the voices of the victims of the Holocaust at Babyn Yar.

Ukraine’s multi-ethnic history has been increasingly important to contemporary writers who are seeking to help envision the future of Ukraine as a civic society. The Jewish writers of Ukraine’s past, who were themselves negotiating the competing forces of tradition, enlightenment, and empire, help them to do this.

For further reading:

Gennady Estraikh, In Harness: Yiddish Writers’ Romance with Communism (Syracuse: Syracuse U.P., 2005)

Amelia Glaser, Jews and Ukrainians in Russia’s Literary Borderlands (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2012)

Mikhail Krutikov, Der Nister’s Soviet Years (Bloomington: Indiana U.P., 2019)

Olga Litvak, Haskalah: A Romantic Movement in Judaism (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers U.P., 2012)

Irene Rima Makaryk and Virlana Tkacz, Modernism in Kyiv: Jubilant Experimentation (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010)

Natan M. Meir, Kiev: Jewish Metropolis: A History (1859-1914) (Bloomington: Indiana U.P., 2010)

Kenneth B. Moss, Jewish Renaissance in the Russian Revolution (Cambridge, MA: Harvard U.P., 2009)

Harriet Murav, David Bergelson’s Strange New World (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2019)

Myroslav Shkandrij, Jews in Ukrainian Literature (New Haven: Yale U.P., 2009)

Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, The Anti-Imperial Choice: The Making of the Ukrainian Jew (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009)

Steven J. Zipperstein, Pogrom: Kishinev and the Tilt of History (New York, Norton, 2018)

Want to learn more about the Jews of Ukraine, past and present? Sign up for My Jewish Learning and JTA News’ email series to learn more about the complicated Jewish history of Ukraine and how the past sheds light on the battles unfolding today.