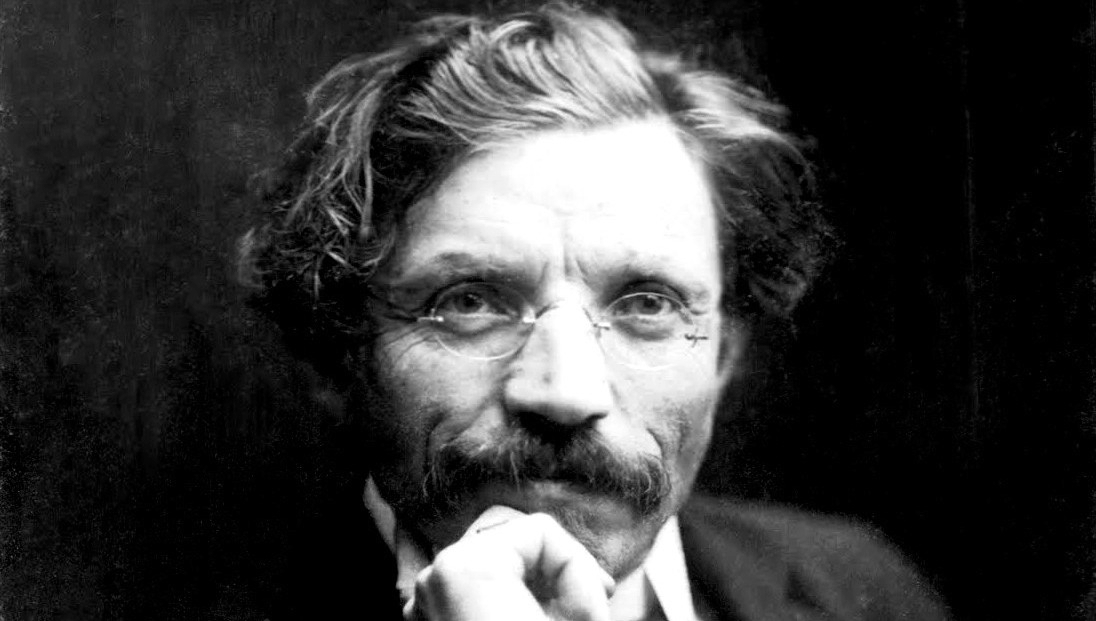

Sholem Aleichem, the most beloved classical Yiddish writer, was born Sholem Rabinovitz in 1859 in Pereyaslav, Ukraine. His father — a merchant — was interested in the Russian Haskalah (Jewish Enlightenment), and the young Sholem was exposed to modern modes of thinking in addition to traditional Judaism. Sholem attended the heder (Jewish school) in Voronkov, the town his family moved to when he was young, and in his teenage years he graduated with distinction from a Russian gymnasium.

Like his contemporaries Mendele Mokher-Sefarim and I.L. Peretz, Sholem Aleichem originally wrote in Hebrew, and he contributed to a number of Hebrew weeklies. Literature was the purview of maskilim (proponents of the Jewish Enlightenment), and for the maskilim, Hebrew was the appropriate language of Jewish high culture. It was the traditional language of Jewish scholarship, and it was considered more sophisticated than Yiddish — the language of the people. Indeed, when the 24-year old Sholem Rabinovitch published his first Yiddish story, “Tsvey Shteyner” (“Two Stones”), he used the pseudonym Sholem Aleichem to disguise himself from his father, who Sholem supposed would be disturbed by his choice of language.

Meaningful Pseudonym

But Sholem Aleichem found his voice in Yiddish. His writing, though far from unsophisticated, was about the masses and for the masses. “Sholem Aleichem” was more than just a pen name. Sholem Aleichem was Sholem Rabinovitch’s tragic-comic persona, a character who mediated the tales of the people to the people. The name itself is significant. “Sholem Aleichem” is a Hebrew greeting, meaning literally “Peace be upon you,” but a more appropriate translation might be: “What’s up?” Sholem Aleichem’s work was a dialogue with the people written in a verbal and cultural language that would have maximum resonance.

This literary attitude manifested itself in the structure of Sholem Aleichem’s work as well. Though Sholem Aleichem wrote novels and plays, he is perhaps best remembered for his fictional confessions, letters and monologues, written in the voice of the simple religious Jew. As Harvard Yiddish scholar Ruth Wisse has written, “Just as Samuel Richardson and Daniel Defoe used ‘discovered’ diaries and letters, pseudobiography… to win the trust of new English readers by insisting their books delivered other people’s words, so too did Sholem Aleichem often present himself as the intermediary between his characters and his readers to attest to the actuality of his creations.”

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

One such character was Menakhem-Mendl, whose “letters” Sholem Aleichem first published in 1892. Menakhem-Mendl is a schlimazel (habitually unlucky person) who travels through Russia with his wife, Sheyne Sheyndel, trying to make his fortune with failed scheme after failed scheme.

The Tevye Stories

A similar theme is evident in the earliest tale about Sholem Aleichem’s most famous protagonist: Tevye the Dairyman, the basis for the show and film Fiddler on the Roof. The first Tevye story, “Tevye Strikes it Rich,” was a monologue, published in 1894. In it, Tevye tells us how he earned enough money to set up a dairy. On his way home from a day working in the fields, he came across a woman and her daughter who are lost. After getting over the fear that they are demons, he escorts them home and is rewarded for his heroism. But his luck doesn’t last long.

In the second Tevye story, “The Bubble Bursts,” published in 1899, the bubble bursts. Tevye is brought into a doomed money-making scheme by none other than Menakhem-Mendl, who is a relative of Tevye’s (by marriage twice removed).

Of course, all of this is ample material for comedy. But aside from his farcical plots, Sholem Aleichem also employed stylistic humor. In a classically rabbinic manner, Tevye lives his life intertextually, sprinkling his speeches with biblical verses. Oftentimes, Tevye mangles these verses, and though some believe Sholem Aleichem created Tevye this way to present him as an ignorant Jew, it’s more likely that the humor is not in Tevye’s naivete, but in our not knowing when he is purposefully misquoting and when he isn’t.

Because of the humorous elements in his writing, Sholem Aleichem is often thought of as a comic writer, but there is an undeniable darkness to his work. The great critic Irving Howe wrote:

As I read story after story, I find that as the Yiddish proverb has it, ‘a Jew’s joy is not without fright,’ even that great Jew who has in his stories brought us more joy than anyone else… a clock strikes 13, a hapless young man drags a corpse from place to place, a tailor is driven mad by the treachery of his perceptions, the order of shtetl life is undone even on Yom Kippur, Jewish children torment their teacher unto sickness. And on and on.

Vast Popularity

Sholem Aleichem connected with a vast chunk of world Jewry. He reached an unprecedented level of fame in his lifetime. Jews from all around the world and of all religious backgrounds read his work. He lived in many places as well. In 1906, Sholem Aleichem left Kiev after the pogroms there and went to live in Lemberg. Then he left for New York, where he hoped to make a living writing and staging plays. But New York was a financial failure for him, and he returned to Europe and was forced to do reading tours to support himself. Sholem Aleichem soon fell ill with tuberculosis, which would plague him for the last eight years of his life.

And yet these physical and financial difficulties were wholly incommensurate with his popularity. Sholem Aleichem’s 50th birthday in 1909 was celebrated all around the world, and when he returned to New York in 1914, he was welcomed with a party at Carnegie Hall. As Howe put it, “Every Jew who could read Yiddish, whether he was orthodox or secular, conservative or radical, loved Sholem Aleichem, for he heard in his stories the charm and melody of a common shprakh, the language that bound all together.”

Sholem Aleichem was a prolific writer. He wrote six novels between 1884 and 1890 alone. He wrote romantic novels and political ones. (He was affiliated with the burgeoning Zionist movement, and in 1898, published part of a Zionist novel named Moshiekhs Tsaytn, The Times of the Messiah).In 1894, the same year the first Tevye monologue appeared, Sholem Aleichem published his first full-length play, Yaknehoz. Later plays included a stage version of his romantic novel Stempenyu, produced during his disappointing residence in New York, and Di Goldgreber (The Gold Diggers), which he wrote in Berlin after leaving New York.

Sholem Aleichem was not just a writer of Yiddish fiction. He was also one of its most devoted advocates. In the late 1880s, Sholem Aleichem founded (and funded) Di Yidishe Folksbibliotek, an annual journal that published the works of most of the important writers of the period, including Mendele Mokher Seforim and I.L. Peretz. He brought prominence to Yiddish writing that would have been unfathomable to his literary ancestors.

Sholem Aleichem died in New York on May 13, 1916. For many years, his readership continued to grow, particularly through the Hebrew translations composed by his son-in-law, Y.D. Berkowitz. Sholem Aleichem, named after a ubiquitous Jewish greeting, had become — and perhaps still is — the ubiquitous name of Jewish literature.