Commentary on Parashat Bereshit, Genesis 1:1-6:8

The Torah portion of Bereshit opens with a description of God’s creation of the universe. According to a midrash, God actually created something before creating the physical universe: repentance and forgiveness. It’s good that God did this, as the very first human being would quickly need them, and each following generation, down to today, would as well.

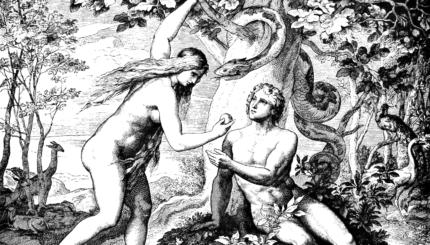

After God creates the first human beings, Adam and Eve, God places them in the Garden of Eden with one commandment — do not eat from the tree of knowledge of good and evil. But they do so almost immediately. The Talmud in Sanhedrin teaches that Adam ignored this single commandment after just ten hours of his existence. Only two hours later, he and Eve were permanently banished from Eden. “Adam did not sleep in this place of honor (the Garden of Eden) for even one night,” the Talmud states. This teaching implies that making mistakes, even big ones, is an essential aspect of our nature. God expects us to err. That is why God banishes but does not destroy Adam.

In an ironic twist, Adam learns about the possibility of forgiveness from his son Cain, who was also punished with exile. Another midrash explains that after Cain murders his brother Abel, God condemns him to live as a “drifter and a nomad” — nah v’nad in the original Hebrew. But Cain doesn’t become a perpetual nomad. A few verses later, we learn that he settles in the land of Nod, whose very name sounds similar to the second word in the Hebrew phrase above. God must have forgiven Cain if he had settled in one location and founded a city there.

This midrash imagines Adam learning from his son Cain about the power of forgiveness. Adam smacks his face in astonishment and is overwhelmed with joy when he learns about God’s desire to forgive. He exclaims that his shame over breaking God’s commandment dissipates when he learns about repentance. In fact, he then composes a song praising God for the gift of forgiveness.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

We are all created in God’s image, but that doesn’t make us perfect. God knows that making mistakes is in our nature. That’s why God created forgiveness before creating the world. What a cold world it would be if God did not forgive us, if others did not forgive us, and if we did not forgive ourselves for things we regret.

This need for forgiveness is especially apparent when we grieve the loss of someone dear to us. Sometimes we were the source of an unpleasant encounter with a loved one. But more often, we wrongfully blame ourselves. How can we not look back on such interactions and imagine alternative scenarios that would ease our guilt? Our memories tend to judge us harshly — that’s how memory works, and that’s why we need forgiveness.

We can forgive ourselves for lost opportunities to mend a relationship even after a loved one has died by incorporating and expressing their better values. We can honor the memories of our loved ones by extending forgiveness to others who may have hurt us. And we can show that their influence continues after death by enjoying our relationships more fully.

This article initially appeared in My Jewish Learning’s Reading Torah Through Grief newsletter on Oct. 21, 2022. To sign up to receive this newsletter each week in your inbox, click here.

Looking for a way to say Mourner’s Kaddish in a minyan? My Jewish Learning’s daily online minyan gives mourners and others an opportunity to say Kaddish in community and learn from leading rabbis.