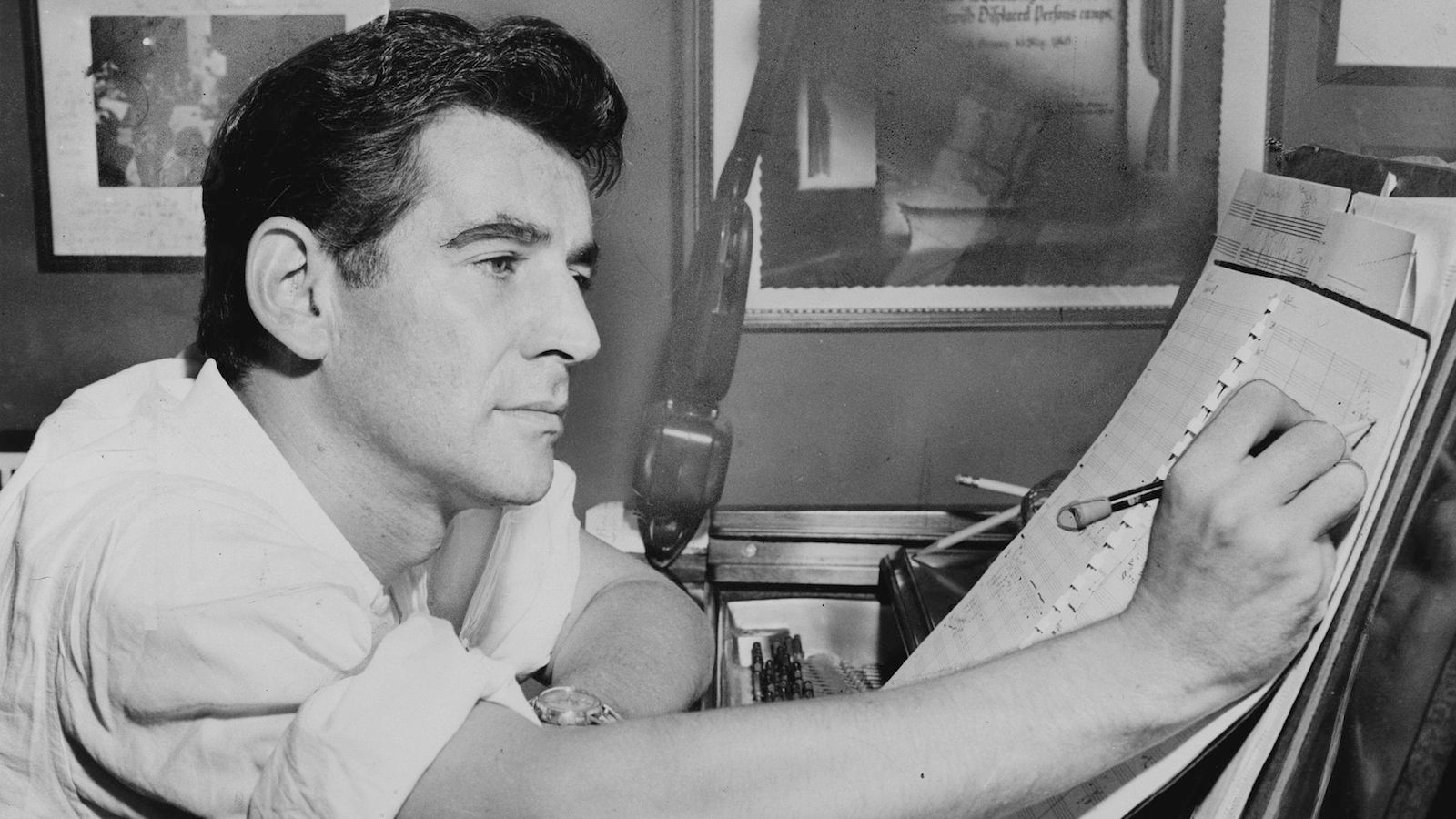

American audiences of all backgrounds swelled with pride as Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990) became the first native son to overcome the European hegemony over conducting positions with ranking world orchestras. Bernstein was only 26 when he captured America’s heart–and respect–by stepping into the breach created by an ailing Bruno Walter and leading the New York Philharmonic Orchestra in a critically acclaimed concert. The previously anonymous, young assistant conductor was catapulted by that success into a career unprecedented in the history of Western music of any sort. Excelling in every venue he touched, Bernstein won praise as a conductor, pianist, teacher, and composer of a wide variety of musical forms.

Bernstein’s musical successes were as much a personal victory for him as they were a source of vicarious accomplishment for America. Bernstein had pursued his musical education over the strong objections of his father, who had urged him toward more conservative pursuits. Interestingly, despite (initially) frustrating his parents with his career choice, he did observe one important family tradition: The Jewish heritage that had been inculcated in him from his youth remained an important aspect of his personal and musical identity.

A Jewish-Themes Symphony

A year before his 1943 conducting debut, Bernstein completed his first symphony, though the work did not receive its premiere until 1944. At the conclusion of that season, the New York critics awarded Bernstein’s Symphony No. 1 their highest accolade, pronouncing it the most impressive new work of the year. One wonders how the critics might have received the work if they had also appreciated its considerable Jewish musical content.

Bernstein subtitled his symphony “Jeremiah,” signaling his intent to tell the story of the prophet who had led Israel in the sixth century B.C.E.Jeremiah’s testimony is recorded in the biblical Book of Jeremiah, and in Lamentations, a series of five poetic odes written by Jeremiah as witness to the horrible destruction of the First Temple and the exile of the Jewish people into Babylonian slavery. The symphony’s three movements are labeled, not with the customary Italian titles announcing form or speed, but with the names of the three “chapters” in Jeremiah’s life: “Prophecy” (his own), “Profanation” (as the people rejected his message), and “Lamentation” (as the prophet’s warnings came true). The didactic intent of this symphony could have been satisfied with these programmatic titles, but Bernstein endowed each movement with unique Jewish musical significance as well…

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

The Kaddish Symphony

Shortly after the premiere of the “Jeremiah” Symphony, Bernstein accepted a commission from the Park Avenue Synagogue to compose a setting of liturgy for the Sabbath service. His “Hashkivenu” for cantor, mixed chorus, and organ was completed in 1945. An impressive work–at times melodious and haunting, at other times dramatic and demanding–it is Bernstein’s only work “for the synagogue.” Since its premiere, its rare performances have been primarily on the concert stage. “Hashkivenu” was also the last “Jewish” work Bernstein wrote for many years. Then, in 1961, Bernstein began work on his third symphony, another programmatic work that he subtitled “Kaddish”…

The Kaddish Symphony is scored for speaker (again a female), soprano solo, adult mixed choir, boys choir, and orchestra. Bernstein wrote the speaker’s text himself and envisioned an era in which humankind was distanced from God and on the verge of self-destruction. The speaker decides to recite Kaddish, her own Kaddish, fearing that there will be no one left alive to say it after her. She chides God for having promised never to destroy the world only to allow His children to do it for Him. God is alternately her father and her paramour (just as the rabbis understood a “masculine” God as the romantic partner of the “feminine” people of Israel). And she is all of humankind–a disobedient child and an angry lover. She calls God to a Din-Torah (a Torah judgment) for breaking Divine promises, but ultimately reconciles herself to Him and allows herself to again speak His praise.

Bernstein’s “libretto” is as replete with Jewish tradition as any text could be. Although all of the imagery derives from the Bible (and is thus accessible to all, albeit in its “Old Testament” form), the speaker’s identity and passions are driven by Jewish history and philosophy, and the Kaddish itself is a uniquely Jewish text. Yet there is not a note of “Jewish” music anywhere in the symphony. Indeed, in this composition, Bernstein made his only forays into an exploration of the possibilities of 12-tone music, a major leap outside the boundaries of accustomed Western practice and Jewish tradition…

Bernstein’s Mass

Bernstein’s 1971 Mass appears to be as far from “Jewish” music as a composer could get. The unorthodox work, commissioned for the opening of the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., was vilified for its theological irreverence and, ironically, was criticized for being too obviously in the consistent musical style of Leonard Bernstein. The composer described the work as “a theater piece for singers, players, and dancers” and scored it for soloist (celebrant), mixed chorus, boys chorus, orchestra, marching band, and electric guitar. In addition to the musicians and dancers who appeared on stage, the work opened with a prerecorded tape of mixed choral singers and percussion played over loudspeakers positioned among the members of the audience. With so many forces and art forms at work, this “blasphemous” work was clearly confusing to traditional Catholics and had many Jews wondering what “their Lenny” was trying to prove.

At least one point that Bernstein wanted to prove was that the Catholic liturgy had clear antecedents in Jewish tradition. The Sanctus section of the Mass has the boys choir singing “Holy, Holy, Holy is the Lord of Hosts”–in Hebrew. Barukh haba be-shem Adonai (Blessed is He who comes in the Name of the Lord) takes on a very different meaning in the context of Catholic worship, but Bernstein accomplished an important educational mission by juxtaposing the two traditions.

The Dybbuk Ballet

Bernstein realized a long-held dream with his 1974 ballet suite, Dybbuk. For years he had toyed with the idea of writing a composition based upon Saul Ansky’s Yiddish play. He had also been eager to work again with choreographer Jerome Robbins, with whom he had collaborated on West Side Story. By the time he approached the project he added another ingredient to the mix, one that derived from the premise of the story itself and that Bernstein later claimed infused every note of the music–Kabbalah [Jewish mysticism]….

It is impossible for the listener to hear Bernstein’s kabbalistic… machinations in the music. What one does hear is a remarkable work, at once contemporary and original, yet infused with the folk spirit of Eastern Europe. Its movements honor the protagonists in Anski’s play, but they also pay tribute to Bernstein’s forebears and to his strong sense of connectedness to his Jewish heritage.

The workaholic Bernstein was often criticized for not focusing on one musical pursuit. Many felt that he would have achieved even greater success had he focused exclusively on either conducting or composing (and excluded the teaching and piano performance that remained an important and fulfilling part of his life). Bernstein’s admirers recognized the multiple interests that drove the man throughout his life and the unique combination of talents that enabled him to succeed in so many venues. The Jewish community benefited as much as any segment of the music world. In particular, Bernstein made an important contribution to concert repertoire, demonstrating convincingly that music can have a decidedly “Jewish” agenda while retaining its “universal” appeal.

Excerpted with permission from Discovering Jewish Music (Jewish Publication Society).

Kaddish

Pronounced: KAH-dish, Origin: Hebrew, usually referring to the Mourner's Kaddish, the Jewish prayer recited in memory of the dead.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.