The Civil War divided Jews as it did all Americans. Southern Jews supported the Confederacy; Northern Jews favored the Union. Prior to the war, Jews as a group never took a public stand on slavery. Although many shared antislavery opinions, they viewed the Christian-oriented abolitionist movement with suspicion. A report to the 1853 meeting of a leading antislavery society accurately described Jewish attitudes:

The Jews of the United States have never taken any steps whatever with regard to the Slavery question. As citizens, they deem it their policy “to have everyone choose whichever side he may deem best to promote his own interests and the welfare of his country.”

The objects of so much mean prejudice and unrighteous oppression as the Jews have been for ages, surely they, it would seem, more than any other denomination, ought to be enemies of caste, and friends of universal freedom.

Jewish Views of Slavery

Two vocal Jewish abolitionists were Ernestine Rose and Rabbi David Einhorn. Rose, a Polish immigrant, was a popular speaker and an outspoken advocate of women’s rights. “Emancipation from every kind of bondage is my principle,” she exclaimed. Einhorn, who had brought about American Judaism’s first major reforms at Baltimore’s Congregation Har Sinai, used his pulpit and his journal, Sinai, to preach, “It is the duty of Jews to fight bigotry since, for thousands of years, Jews have consciously or unconsciously fought for freedom of conscience.”

Yet some Jews held other views of the slavery issue. Rabbi Morris Raphall of New York’s Congregation B’nai Jeshurun was a dramatic orator and writer who had the distinction of being the first Jewish clergyman to deliver an opening prayer for a session of the United States Congress (February 1, 1860).

On National Fast Day he delivered a widely reprinted sermon, “A Bible View of Slavery.” In the North, many were disappointed with his words; Southerners viewed it with satisfaction. “Slavery has existed since the earliest time,” the rabbi wrote. “Slave holding is no sin,” he declared, since “slave property is expressly placed under the protection of the Ten Commandments.” Rabbi Einhorn was aghast and forcefully rebutted Raphall’s words in Sinai.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Internal Disagreements

Dismissing Raphall’s literal interpretation of the Bible as representative of all Jewish thought in America, Einhorn insisted that just because a particular practice was condoned in the Bible did not make it right for modern times. The real question, according to Einhorn, was: “Is slavery a moral evil or not?” He argued that the spirit of Judaism, as opposed to its letter, demanded the abolition of slavery. “The Bible” he wrote, “merely tolerates this institution as an evil not to be disregarded and therefore infuses in its legislation a mild spirit gradually to lead to its dissolution.”

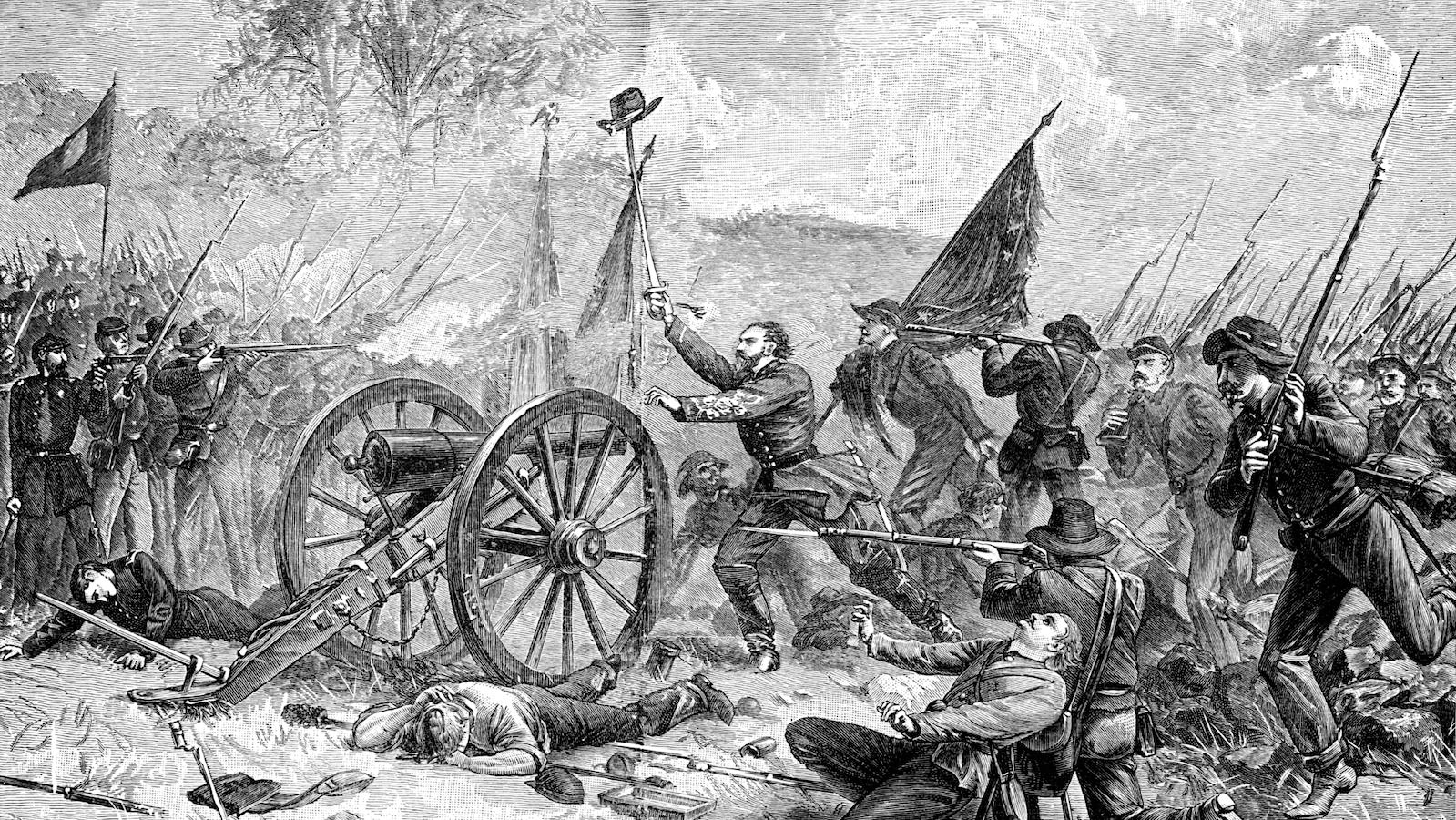

Thousands of Jews volunteered and many died on both sides of the conflict. An estimate by Congressman Simon Wolf placed the number in the Union forces at about 8,400 and in the Confederate forces at about 10,000. Other estimates differ, but it is clear that Jews fought on both sides in numbers greater than their percentage in the general population.

There were nine Jewish generals in the North and several in the South. Jews fought not only for their respective causes, but also for equal treatment for themselves. Six .Jewish soldiers in the Union army received the coveted Congressional Medal of Honor for their bravery. When the war ended, Jewish soldiers returned to their homes to rebuild their country and their lives.

In the North, two events galvanized the Jewish community at large during the war: the appointment of a Jewish chaplain to the military and General Grant’s Order No. 11.

Reprinted with permission from The JPS Guide to American Jewish History (Jewish Publication Society).