Commentary on Parashat Shoftim, Deuteronomy 16:18-21:9

Parashat Shoftim is one of our most neatly packaged Torah portions, beginning with commandments about the necessity for appointing “magistrates and officials” (16:18) and concluding with a procedure aimed to ensure that people do “what is right in the sight of God” (Deuteronomy 21:9). From its opening words to its concluding phrases, this portion is about righteousness and justice. Yet these concepts are meaningless unless rooted in concrete particulars so they can permeate the lives of those who wish to find meaning in the Torah. These are clearly universal values, but where do we find out about the ways women approach such values and concerns?

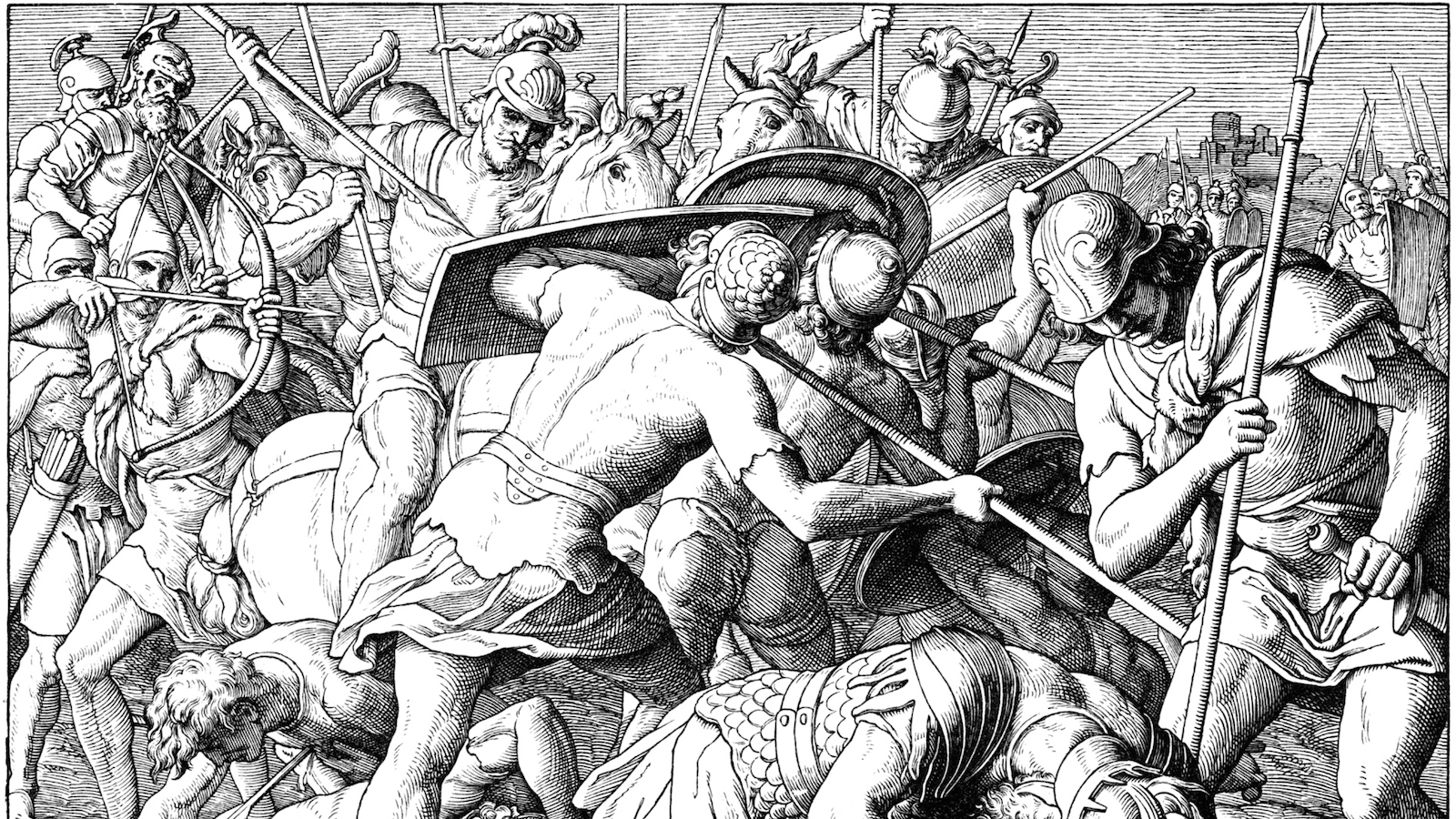

Among the commandments recounted in this portion are those about warfare. Can we retain humanity in a time of war? The Torah portion asks us to attempt every other possible measure before war is undertaken, literally to “call her [that is, the city] to peace” (20:10), which indicates that war should be considered a last resort in resolving a conflict. All world leaders should familiarize themselves with this ethical teaching: negotiate before fighting by actively calling out in peace to one’s opponent. This recalls the active language about Aaron the priest and his sons in Pirkei Avot 1:12, “Be like the disciples of Aaron: love peace and pursue it.”

Real peace needs strong verbs of “calling” and “pursuing” — and real attempts to forge fighting has permeated the ways in which the society approaches war. In discussing Deuteronomy 20:10, Sefer HaChinuch, a medieval compilation of mitzvot, states, “The quality of mercy (rahmaniut) is a good quality; and it is fitting for us, the holy seed, to behave thus in all matters even with our enemies, worshippers of idols.” This notion that we should always behave with rahamim (mercy) — even to an enemy — is one that continues to apply to daily life, as well as to national crises. This would mean that we first would call to that person in peace, prior to arguing or becoming angry, difficult as it may be.

Are there any biblical examples of this mode of discourse? One example concerns a woman who saves an entire city from destruction (II Samuel 20:14-22). That passage tells how Joab, a warrior acting on the king’s behalf, pursues Sheba son of Bichri, the leader of a group that has rebelled and fled to the town of Abel of Beth-maacah. When Joab besieges the city, a “wise woman” employs persuasive rhetoric and feminine imagery to avert war, warning Joab that he risks destroying a “mother city in Israel” (v. 19). Joab assures her that if the people hand over Sheba, he will not attack the city. The woman makes sure that this happens when she convinces the townspeople to cut off Sheba’s head and toss it over the wall. In this case, the wise woman’s sense of mercy and calling out in peace means that one life is sacrificed for the greater good, to avert large-scale bloodshed and ruin.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Parashat Shoftim tells us that if war cannot be avoided, there are humane ways to go about it: “When in your war against a city you have to besiege … you must not destroy its trees” (Deuteronomy 20:19). Why not? The verse continues, “ki ha-adam etz ha-sadeh,” which can be read either as “Are the trees of the field human?” or, alternatively, as “for a human is like a tree.” Trees have the ability to draw water into themselves, and nourish themselves. What will sustain and nurture us? An answer may come from the end of the book of Deuteronomy, when Moses charges all the people — men, women, children, and strangers — to listen to and learn “every word of this Teaching (Torah)” (Deuteronomy 31:12). Just as we may not cut down fruit trees so they may continue to bear fruit, so we must actively study and teach Torah, striving to incorporate it into our hearts and our minds. That way, the quality of mercy will envelop and permeate our individual lives and our society as a whole.

Are there distinct ways that women strive to infuse our world with more mercy and peace? Professor Galia Golan, who has studied Israeli-Palestinian dialogue groups for 25 years, has found that dialogue groups composed of all women differ in certain respects from mixed-gender groups (“Reflections on Gender in Dialogue,” Nashim 6, 2003). She has observed that women tend to start from their shared experiences, beginning the conversation not with an abstract, angry summation of the history of the conflict, but with emotional accounts of their personal experiences. According to Golan, women seem more invested in the ability to “dissolve the psychological barriers obstructing resolution of the conflict, by reversing the dehumanization of the enemy that takes place during a prolonged conflict; expanding understanding of the other’s positions; creating empathy with the other side; and thus paving the way for eventual reconciliation.” Dialogue shows unique ways that women call one another to peace, reminding us that through our words and our actions, we possess the potential to “love peace and pursue it.”

It seems fitting that Parashat Shoftim, which is about justice, ends with a body. The crucial aspect of the perplexing ritual of the eglah arufith (“the brokennecked heifer”) is to force the living to acknowledge their responsibility to the dead. This ritual provides a means to ascertain responsibility for the corpse. According to the Midrash, kindness to a dead person (chesed shel emet) is the truest kindness, for it cannot ever be repaid (Breishit Rabbah 96.5; see also p. 297).

Why do it? It is the right thing to do, both for the collective of society and for the dead individual. It is only in this state of being a collective that society can operate with justice. Through the totality of these laws, the Torah portion defines a just society — true kindness and mercy done to all, whether they are brothers, sisters, or enemies, living or dead, human or tree — so that all may find means of sustenance and peace. These values become societal values when they permeate all aspects of life.

Reprinted with permission from The Torah: A Women’s Commentary, edited by Tamara Cohn Eskenazi and Andrea L. Weiss (New York: URJ Press and Women of Reform Judaism, 2008).

chesed shel emet

Pronounced: KHEH-sed shell EM-ut, Origin: Hebrew, kindness to a dead person, usually used to describe the work of a Jewish burial society or the care of a grave.