The idea that Jews don’t believe in hell was an almost universally accepted truth in my younger religious education, and this remains a commonly held belief today. Many people hold it to be one of the major distinctions between Judaism and Christianity.

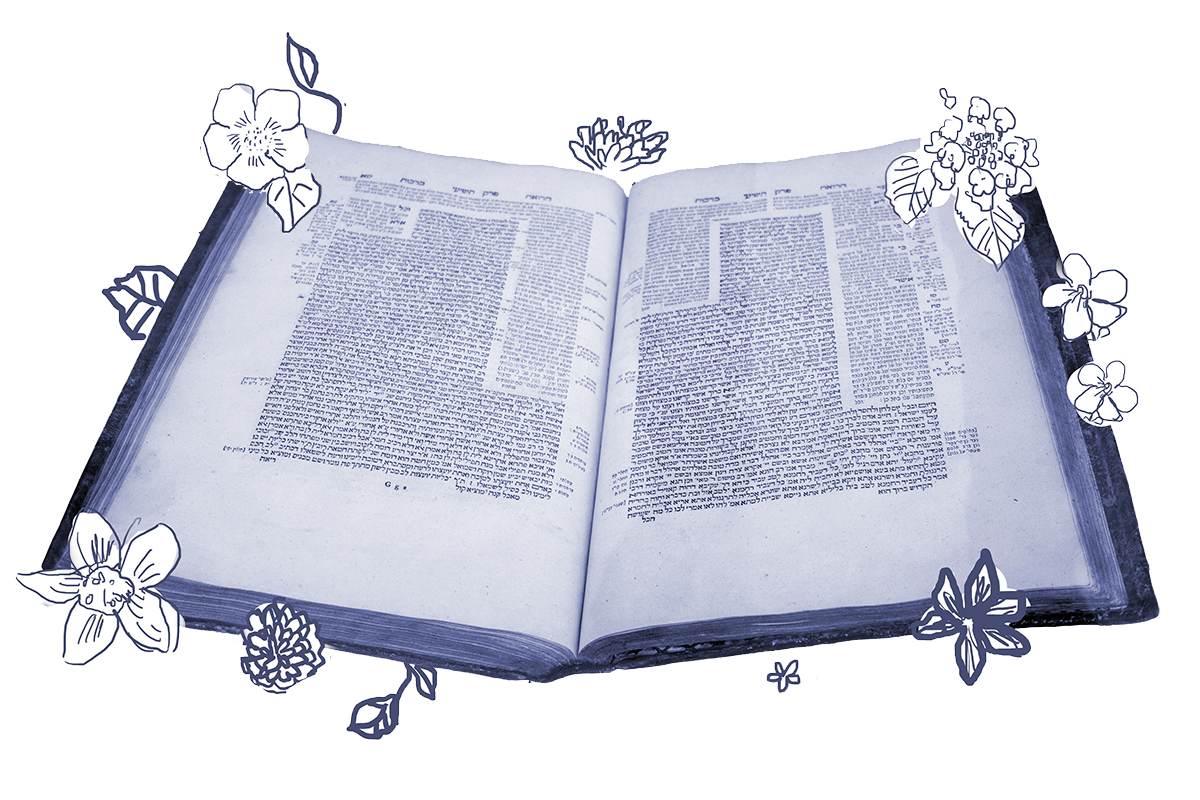

There’s some truth to this idea. Judaism has a complex and at times ambiguous conception of the afterlife. But what then do we do with the mysterious digression on today’s daf?

The rabbis are in a long debate about the nature of Gehenna, a word commonly translated as “hell” but which we can understand as “purgatory” or “the underworld.”

Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi said: Gehenna has seven names, and they are as follows: She’ol, Avadon, Be’er Shaḥat, Bor Shaon, Tit HaYaven, Tzalmavet, and Eretz HaTaḥtit.

She’ol, as it is written: “Out of the belly of the netherworld [she’ol] I cried and You did hear my voice” (Jonah 2:3). Avadon, as it is written: “Shall Your steadfast love be reported in the grave or Your faithfulness in destruction [avadon]?” (Psalms 88:12). Be’er Shaḥat, as it is written: “For You will not abandon my soul to the netherworld; nor will You suffer Your pious one to see the pit [shaḥat]” (Psalms 16:10). And Bor Shaon and Tit HaYaven, as it is written: “He brought me up also out of the gruesome pit [bor shaon], out of the miry clay [tit hayaven]” (Psalms 40:3). And Tzalmavet, as it is written: “Such as sat in darkness and in the shadow of death [tzalmavet], bound in affliction and iron” (Psalms 107:10). And with regard to Eretz Taḥtit, i.e., the underworld, it is known by tradition that this is its name.

For a tradition that supposedly doesn’t believe in the idea of the underworld, this Gemara certainly has a lot of ways to describe it. While the idea of eternal damnation is not normative, today’s daf shows us that the idea of a place of punishment or judgment after death is not absent from Jewish thought.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

The term Gehenna derives from an actual physical location – a small valley in Jerusalem known as Gei Hinnom. But in the rabbinic mind, it is also a quasi-purgatory where, after death, one’s deeds are judged and one can reflect on one’s human shortcomings.

The Gemara’s descriptions of Gehenna here share a physical rootedness – they are largely subterranean. What’s more, almost all of the prooftexts are drawn from Psalms, a text known for evoking the experience of the soul crying out from the (existential) depths.

This passage might feel like it veers sharply away from the discussion with which we began this chapter of Eruvin — the required demarcations around public wells to make them fit for use on Shabbat. But there is a poetic resonance here. Wells are deep pits carved into the ground. To permit the use of a well on Shabbat, there must be an eruv, but the eruv doesn’t have to be entirely contiguous. It only needs to indicate the outer boundaries of the well’s domain – we fill in the gaps in our mind.

Likewise, the rabbis imagine Gehanna to be a deep pit, and are equally curious about its boundaries (earlier on the daf, they inquire as to the location of its entrance).

What these two conversations share is an inquiry into what lies beneath the surface, and the ways we cross into and out of liminal spaces.

Read all of Eruvin 19 on Sefaria.

This piece originally appeared in a My Jewish Learning Daf Yomi email newsletter sent on August 28, 2020. If you are interested in receiving the newsletter, sign up here.