Are you interested in joining the world’s largest book club?

Daf yomi (pronounced dahf YOH-mee) is an international program to read the entire Babylonian Talmud — the main text of rabbinic Judaism — in seven and a half years at the rate of one page a day. Tens of thousands of Jews study daf yomi worldwide, and they are all quite literally on the same page — following a schedule fixed in 1923 in Poland by Rabbi Meir Shapiro, the founder of daf yomi, who envisioned the whole world as a vast Talmudic classroom connected by a global network of conversational threads.

A page a day doesn’t sound too daunting, until you consider that each Talmudic page is actually a double-sided folio comprised of multigenerational conversations among the rabbis of the first few centuries of the Common Era, dealing with everything from what to do if your camel knocks over a candle and sets a store on fire to the consequences of embarrassing another person while he is naked.

The Talmud is divided into 37 volumes, known as tractates, each of which deals with different aspects of Jewish law, from vows to marriage to the logistics of offering sacrifices in the ancient Temple. But the subjects of the tractates are in part only nominal, because the Talmud is a highly discursive text, proceeding by association rather than by any rational scheme. Every page presupposes knowledge of other pages, which is why it is difficult to start learning without prior background. But every page connects to conversations on other pages, and so once you have started learning, it’s almost impossible to stop.

Here are answers to some frequently asked questions by those who are thinking about embarking on this wild seven-and-a-half year journey through one of the most quirky, irreverent, surprising and intriguing works in the Jewish literary canon:

Do I need to be religious — or Jewish — to study Talmud?

Can I study Talmud even if I have little or no Hebrew background?

What version of the Talmud do you recommend I use, and where can I find it?

What resources and study aides are most helpful?

Does it make sense to start in the middle of a daf yomi cycle, or should I wait for the next cycle to begin?

One page a day, seven days a week, is quite a relentless pace. Do you have any tips for staying on schedule? What if I fall behind?

What keeps you going on days when you have no motivation to learn or begin to lose interest?

How do you keep track of everything you learn?

What might I get out of studying daf yomi?

1. Do I need to be religious — or Jewish — to study Talmud?

Absolutely not! The Talmud deals with all aspects of Jewish life, but you don’t need to be a practicing observant Jew to appreciate the subjects under discussion, many of which have broader and more universal resonance, such as what our obligations are when we chance upon an object that someone else has lost. Although the Talmudic rabbis followed the Torah’s commandments, their theological orientation was often so bold and heretical that some of their statements may be best appreciated by those who are not themselves devout. And unlike later works that followed from it, the Talmud is not a law code intended to tell Jews how to behave but a record of rabbinic legal conversations in which many of the questions are left open and unresolved. It is a text for those who are living the questions rather than those who have found the answers. And so if you are a thinking, questioning person who does not take anything at face value, then Talmud study may be for you.

2. Can I study Talmud even if I have little or no Hebrew background?

Yes. The Talmud is actually written in a combination of Hebrew and Aramaic, which was the lingua franca of Jews living in Babylon (now Iraq) during the first few centuries CE. But it is available in multiple English translations, both in print and online. Many passages in the Talmud involve Midrash (rabbinic interpretations of biblical passages) and a close reading of biblical sources; certainly knowledge of Hebrew is helpful in appreciating the linguistic connections the Talmud frequently draws. But Talmud can be studied on many levels – it is often compared to a sea because of its vastness and depth, and as with a sea, you can skim the surface, swim underwater, or become a deep-sea diver and learn about all the flora and fauna on the ocean floor. You can learn superficially or deeply, and yes, some of that depends on your level of Hebrew.

3. What version of the Talmud do you recommend I use, and where can I find it?

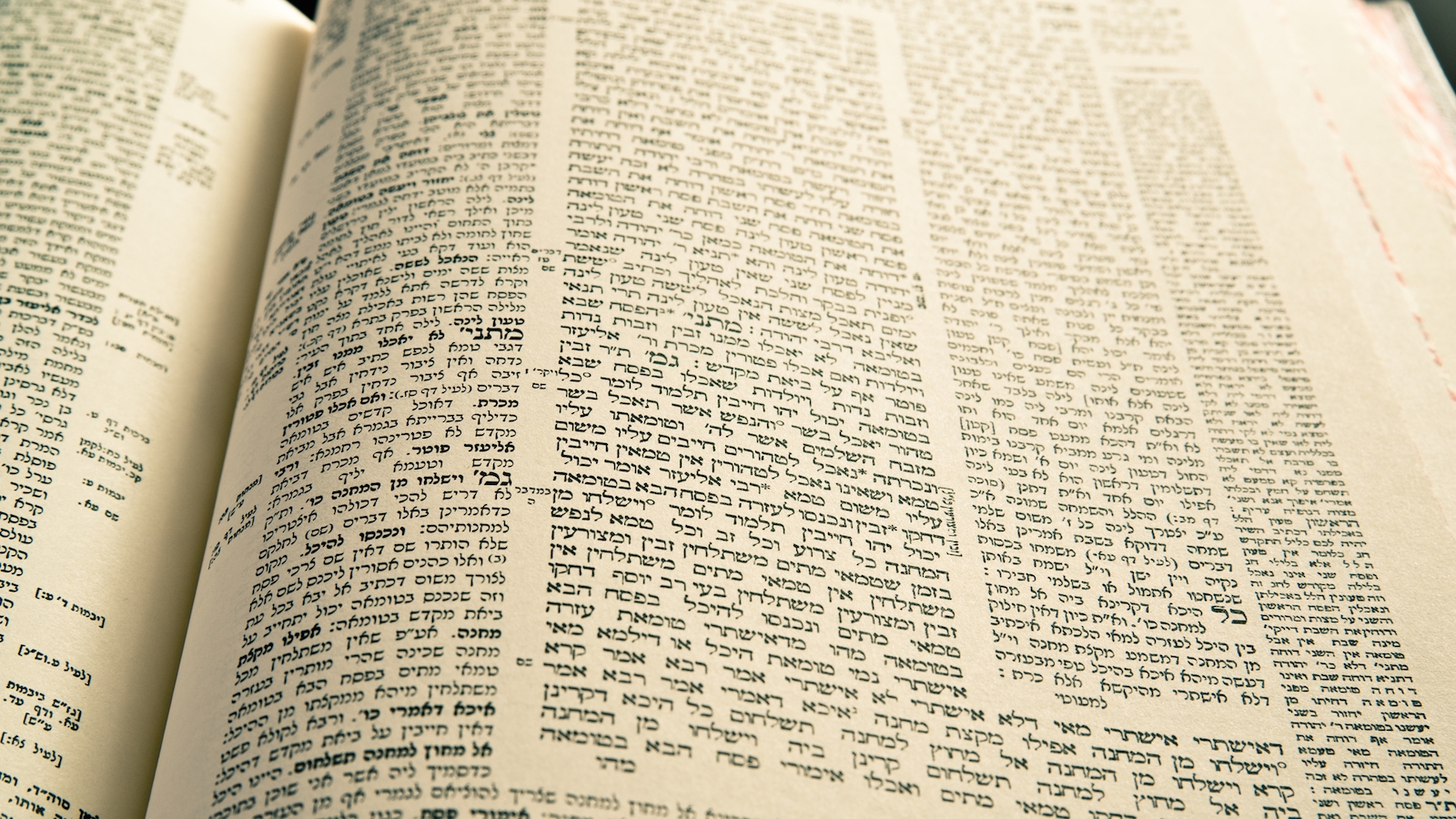

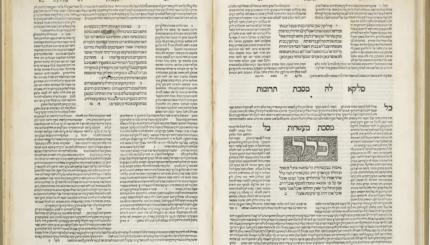

The version of the Talmud that has become most standard and most widely studied in traditional settings is the Vilna Shas, first printed in 1835. This is what people commonly imagine when they picture a page of Talmud — a block of Hebrew text in the center of the page surrounded by marginal commentaries. But there are also more accessible versions of the text, such as the modern Hebrew edition published with the very helpful commentary of Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, which is currently being translated into English as the Koren Talmud Bavli and available for free online at Sefaria.org. (Sefaria also offers a direct link to the current day’s page of Talmud from its homepage.) Artscroll publishes a translation that will be best suited to traditional Jews, and the Soncino commentary—available for free online at www.halakhah.com — is readable if somewhat archaic.

4. What resources and study aides are most helpful?

There is a vast array of English-language daf yomi podcasts consisting of recordings of daf yomi classes taught by rabbis and other scholars ranging in length from the five-minute daf yomi shiur (lesson) to lessons that are well over an hour long. The standard daf yomi podcast is probably about 45-50 minutes. One very accessible, clear explication of the daily page, is Michelle Farber’s dafyomi4women, which, though taught by a woman to a group of women in Raanana, Israel, is as valuable for men as for women. A number of websites, such as the Orthodox Union’s Daf Yomi Resources Page, offer various supplemental materials, such as summaries and commentaries, for the daf yomi.

And finally, if you are interested in reading secondary sources that will introduce you to the world of the rabbis and the nature of Talmud as a literary genre, you might consider such books as Ruth Calderon’s A Bride for One Night, a collection of fictional tales based on Talmudic narratives; Binyamin Lau’s The Sages, a collection and interpretation of stories about various Talmudic figures, organized chronologically; and my own book, If All the Seas Were Ink, a memoir of seven and a half years of daf yomi study that is at once a guided tour of the Talmud and a deeply personal tale of love and loss.

5. Does it make sense to start in the middle of a daf yomi cycle, or should I wait for the next cycle to begin?

A new daf yomi cycle begins only once every seven and a half years — the next cycle begins on June 8, 2027. But we begin a new tractate covering a new topic every few months, and so you can start at the beginning of a tractate without feeling lost. Numerous daf yomi calendars, such as this one, are available online, and you can also download daf yomi calendars to your phone.

6. One page a day, seven days a week, is quite a relentless pace. Do you have any tips for staying on schedule? What if I fall behind?

The key to sticking with daf yomi is to find a way to incorporate a bit of learning into your schedule every day, but this learning can take many forms. The rabbis in Tractate Taanit teach that “a person should always be pliable like a reed, and not rigid like a cedar” (Taanit 20a). It helps to be flexible about what it means to learn the page. Some days you may be able to sit down and read the page itself, along with related commentaries and study aides; other days you may have time to listen to a podcast while driving to work or folding the laundry. The point is learning every day, not how you do it. If you fall behind, it helps to have a specific day of the week designated for catching up. It also helps to learn with a study partner or as part of a class, because then you are accountable to someone else. Of course, you are always accountable to the schedule of daf yomi, which is sort of like a treadmill — it just keeps moving forwards, and you need to keep running. It is exhausting at times, but it also keeps you on your toes.

7. What keeps you going on days when you have no motivation to learn or begin to lose interest?

A commitment to learning daf yomi is sort of like a marriage — you’re in the relationship for the long haul, even if most days there are no passionate sparks. Sometimes it’s hard to find anything meaningful or relevant on the page, but perhaps it helps to imagine those pages as the context for the more exciting material that will follow a few days later. Without the context, you cannot fully appreciate that fabulous story about the man who mistakes his wife for a prostitute, or the unicorns that could not fit into Noah’s ark. On pages where the topics seems less interesting, it sometimes it helps to pay attention not just to what the rabbis are saying, but to how they transition from one subject to the next, such that a discussion of sex with a virgin suddenly morphs into a discussion of how to avoid hearing something untoward by sticking one’s fingers in one’s ears—as if to suggest that all acts of penetration are one and the same. To learn daf yomi, you have to allow yourself to be carried along for the ride — and while it’s almost never smooth sailing, some days are certainly bumpier than others.

8. How do you keep track of everything you learn?

Learning daf yomi is a bit like zooming through a safari on a motorcycle – there is so much to take in, and yet you are moving ahead at a rapid clip. There are many ways to take stock without slowing down. You might write about something you’ve learned (see, for instance, my own daf yomi limericks), or draw a picture summarizing something on the daf (see these incredible sketches). You may simply write notes in the margins, summarizing what you have learned. In my case, many years of marginal notes scribbled in my volumes of Talmud became the basis of a memoir, If All the Seas Were Ink.

9. What might I get out of studying daf yomi?

When I first started learning, I didn’t think the Talmud could possibly have anything to say to me personally. But I discovered that when you learn deeply and allow yourself to listen carefully to what the text has to say, you find yourself living against the backdrop of the Talmud — such that the text is a commentary on life, and life is a commentary on the text. The rabbis teach in Tractate Eruvin (54a) that “one who is walking alone his way and has no companion should occupy himself with the study of Torah.” At first the Talmud was my companion during a rather lonely stretch of life. But through my study of Talmud, I overcame a difficult period in my life and found a way forward. And so I followed the Talmud, but the Talmud has also followed me through the various twists and turns my life has taken — through divorce, dating, aliyah (immigration to Israel) marriage, pregnancy and motherhood. I invite you to join me in this journey.

daf yomi

Pronounced: dahf YO-mee, Origin: Hebrew, daily page, refers to the daily page of Talmud many people read together in groups over a seven-and-a-half year cycle.

Talmud

Pronounced: TALL-mud, Origin: Hebrew, the set of teachings and commentaries on the Torah that form the basis for Jewish law. Comprised of the Mishnah and the Gemara, it contains the opinions of thousands of rabbis from different periods in Jewish history.

masechet

Pronounced: muh-SEKH-et, Origin: Hebrew, a tractate of the Talmud.

Mishnah

Pronounced: MISH-nuh, Origin: Hebrew, code of Jewish law compiled in the first centuries of the Common Era. Together with the Gemara, it makes up the Talmud.

Gemara

Pronounced: guh-MAHR-uh, Origin: Aramaic, a compendium of rabbinic writings and discussions from the first few centuries of the Common Era. The Talmud comprises Gemara and the Mishnah, a code of law on which the Gemara elaborates.

Midrash

Pronounced: MIDD-rash, Origin: Hebrew, the process of interpretation by which the rabbis filled in “gaps” found in the Torah.

aliyah

Pronounced: a-LEE-yuh for synagogue use, ah-lee-YAH for immigration to Israel, Origin: Hebrew, literally, “to go up.” This can mean the honor of saying a blessing before and after the Torah reading during a worship service, or immigrating to Israel.