Commentary on Parashat Tetzaveh, Exodus 27:20-30:10; Deuteronomy 25:17-19

Most years, this Torah portion is read during the week preceding Purim. The connection between the portion and Purim is not immediately apparent. Tetzaveh is filled with exacting details about the assembly of the priestly garments and the ritual role Aaron and his sons are to perform as anointed priests. The Book of Esther is a melodramatic tale of threat, intrigue, and ultimate redemption through plot twists and the reluctant heroism of a beautiful queen.

While the plots and purposes of these texts are vastly different, each in its own way, asks us to confront an absence. Tetzaveh is the only Torah portion from the beginning of the Book of Exodus until the end of Deuteronomy where the name of Moses does not appear. And Esther is one of only two books of the Bible where the name of God does not appear. These absences are cause for abundant commentary in each individual case, but the relationship between the two texts seems to receive only passing mention. What insight can this parallel presence of absence convey?

Why Is Moses Missing?

Many commentators speculate as to why Moses’ name is absent from Parashat Tetzaveh. One theory is that the omission is meant to acknowledge the anniversary of his death, which is said to be the seventh of Adar, just one week before Purim. Another theory is that Moses’ name is left out as divine admonishment for his jealousy over Aaron’s appointment as chief priest. Still others maintain that in his humility and self-effacement, Moses graciously cedes the role to his brother and absents himself from the narrative, so to speak, to make this clear.

Regardless of the reaction that Moses mayor may not have experienced when his brother became the head priest instead of him, the narrative suggests that although his name is not mentioned, Moses remains God’s agent-the enabler for all that is to happen. This is made evident through an unusual grammatical formulation found in the portion’s opening verses.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Elsewhere in the Torah, God’s commands to Moses are stated in the simple imperative: “instruct” (tzav) or “speak” (dabber). In Tetzaveh, however, three instances of an additional pronoun appear, giving extra emphasis to the actor responsible for the actions. Translating the text more literally, the first verse of the parashah (Exodus 27:20) reads: ”And you, yourself shall command the children of Israel.” Shortly thereafter, we read: “And you, bring near to yourself your brother Aaron, with his sons, from among the Israelites, to serve Me as priests” (Exodus 28:1). The same grammatical form appears two lines later: “You, yourself speak to all who are skillful, whom I have endowed with the gift of skill, to make Aaron’s vestments” (Exodus 28:3).

It’s All You

The 16th-century commentator Moshe Alshekh suggests that this repeated double emphasis is God’s way of saying to Moses, “It’s all really you. You have a greater share in it than anyone. All fulfill themselves through you” (cited in Nehama Leibowitz, Studies in Shemot, 1980, p. 526). Perhaps such language means to tell us that Moses is not absent at all. Rather, his presence is momentarily diminished so that other leaders can step forward to serve the broader needs of the community.

Just as we can see Moses as a behind the scenes mover in the portion, so too, can we see God as filling a similar role in the Purim narrative. While many interpret the Purim story as an instance when the Jews achieved victory through their own actions-without waiting for divine intercession-the classic rabbinic interpretation is that God was hidden from view, but not absent. In BT Chullin 139b, the Rabbis made this point through a biblical proof text, asking: “Where is Esther indicated in the Torah? In the verse “I will surely hide (astir) My face” (Deuteronomy 31:18). The Hebrew word astir (“I will hide”) serves as a wordplay on Esther’s name.

We can extend the wordplay even further by considering that the Hebrew word Megillah shares the same root as the verb “to reveal” (g-l-h). Thus, the Book of Esther can be read playfully as “revealing the hidden.” God’s presence is revealed through Mordecai’s conviction and Esther’s courage. God’s presence is revealed in the triumph of good over evil, in the flawed but ultimately responsible actions of human beings.

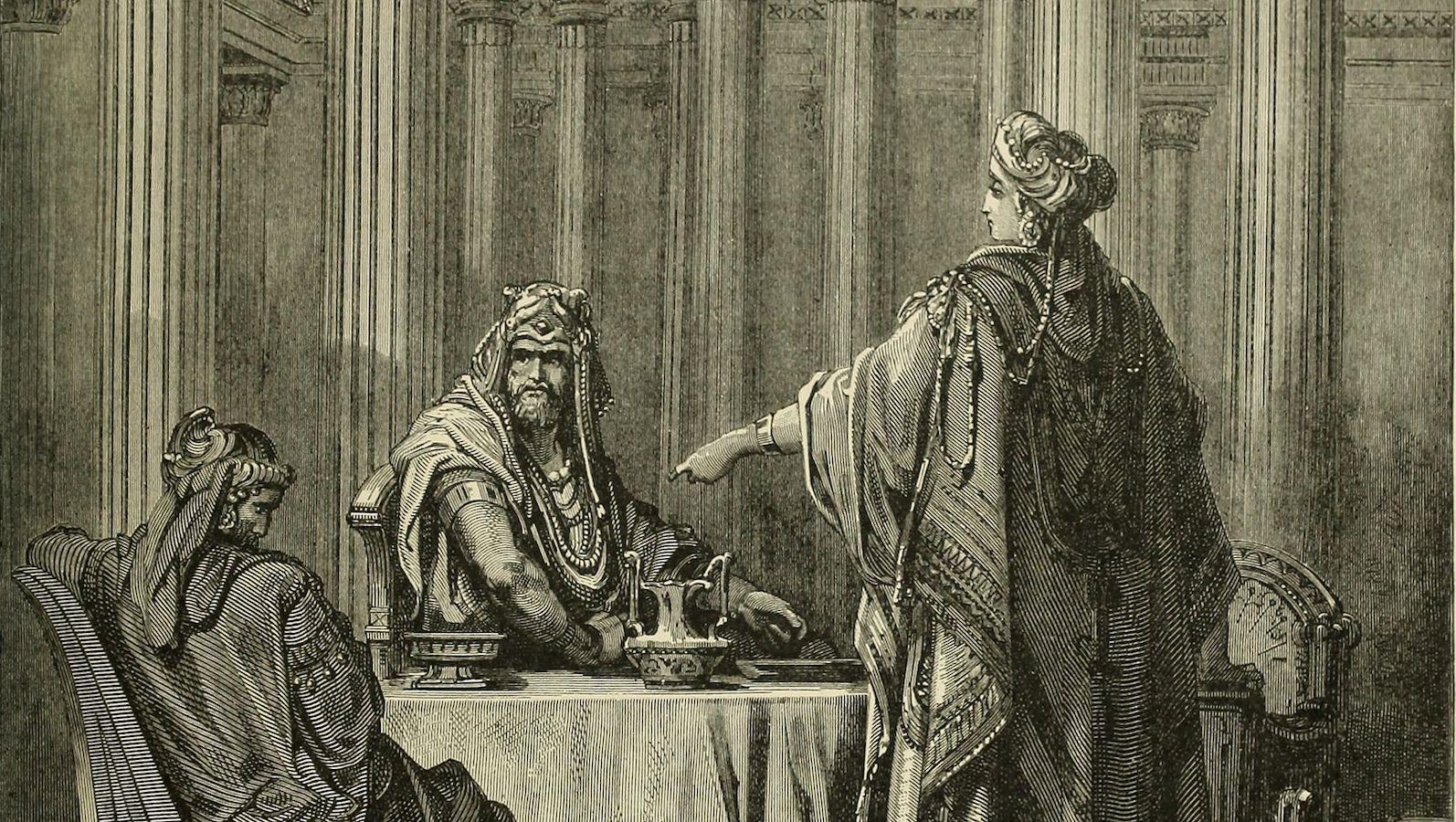

In a typical Purim twist, the biblical text also reinforces the presence of God’s absence by pointing out the consequences of the absence of God’s presence. The story opens with a drunken debauchery hosted by King Ahasuerus, where “he displayed the glory of his kingdom and the richness of his magnificent splendor for many days, for 180 days” (Esther 1:4).

The words used to describe the “glory” and “splendor” of his kingdom are the same words, kavod u’tiferet, that are used in Tetzaveh to describe the priestly garments (28:2, 40; there translated as “dignity and adornment”). In Tetzaveh, the lavish garments are designed to serve and honor God. In Esther, the King’s wealth is evidence of his corruption. The Midrash draws an even more powerful connection by claiming that the riches of Ahasuerus’ kingdom were made up of the spoils of the Temple, including the priestly garments themselves (Ester Rabbah 2.1).

The Purim message that sometimes gets lost in all of the revelry is that a sense of God’s presence in the world, even if hidden and obscure, gives us the strength and moral purpose to cope with uncertainties and imperfections. Parashat Tetzaveh paints a picture of the detail and exacting effort it took for the Israelites to feel God’s presence in their midst. Today, we have no priests and no Temple. The only vestige we have of this experience is the ner tamid, the eternal light, the first thing that God instructs Moses to establish in the opening verses of the portion. This light has come to symbolize the light of Torah. For us, then, the glory and splendor of God’s presence must be felt through the study of Torah and the constant striving to live in its light.

Reprinted with permission from The Torah: A Women’s Commentary, edited by Tamara Cohn Eskenazi and Andrea L. Weiss (New York: URJ Press and Women of Reform Judaism, 2008).

Moshe

Pronounced: moe-SHEH, Origin: Hebrew, Moses, whom God chooses to lead the Jews out of Egypt.

Purim

Pronounced: PUR-im, the Feast of Lots, Origin: Hebrew, a joyous holiday that recounts the saving of the Jews from a threatened massacre during the Persian period.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.

megillah

Pronounced: muh-GILL-uh, Origin: Hebrew, meaning "scroll," it is usually used to refer to the scroll of Esther (Megillat Esther, also known as the Book of Esther), a book of the Bible traditionally read twice during the holiday of Purim. Slang: a long and tedious story or explanation.

Midrash

Pronounced: MIDD-rash, Origin: Hebrew, the process of interpretation by which the rabbis filled in “gaps” found in the Torah.