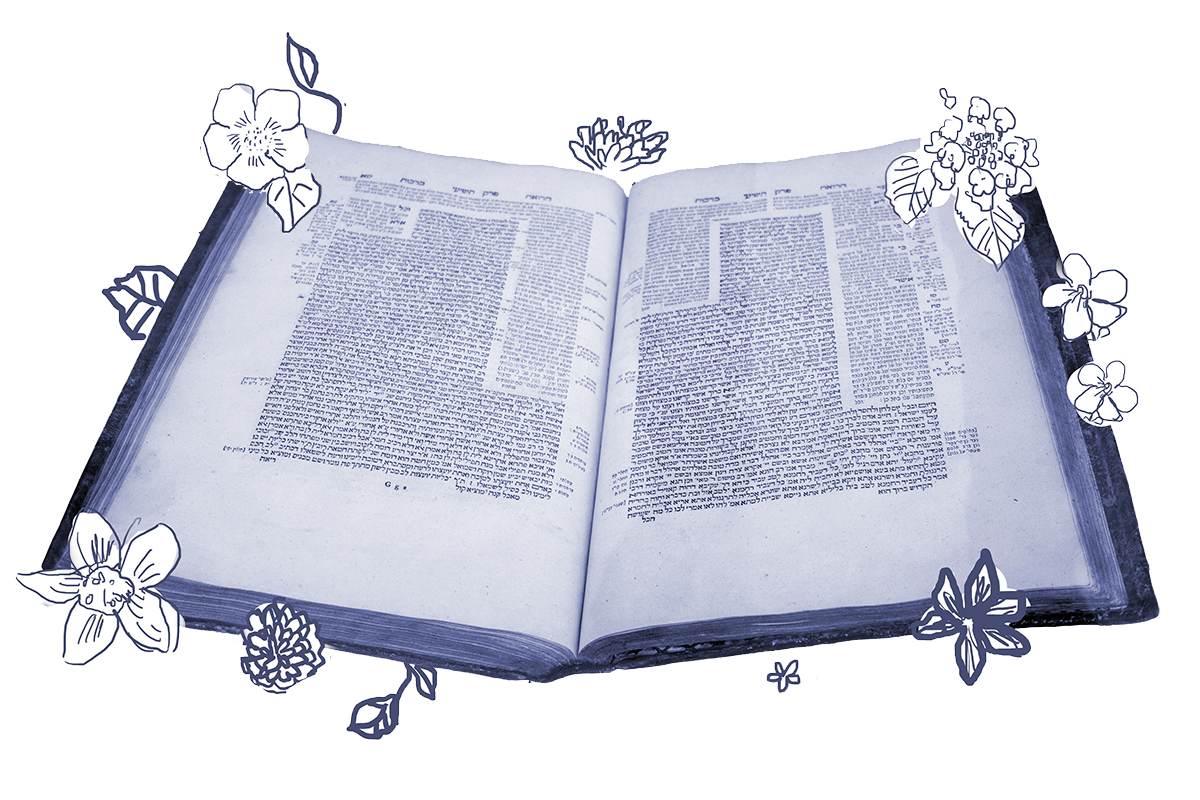

Today’s daf is the last one of chapter five of Bava Metzia. The chapter was full of detailed arguments about what constitutes interest, and it explored various legal fictions that can be used to permit interest payments within the context of business partnerships.

Given that context, the final mishnah of our chapter is striking:

And these people violate the prohibition (of interest): The lender and the borrower and the guarantor and the witnesses. And the rabbis say: Also the scribe (who writes the promissory note).

This mishnah’s scope of who violates the prohibition of usury is far broader than preceding mishnahs in the chapter. It goes on to interpret each of the four mentions of the prohibition on interest in the Torah as referring to the various individuals involved in processing the usurious loan, no matter how official or legal the loan appears to be. No one can claim exemption from having broken the Torah’s laws on the grounds of having been a mere accomplice. Further, anyone involved in a usurious agreement commits the sin of misleading others by making them believe that what they’re doing is perfectly legal. This is symbolized by the injunction in Leviticus 19:14 against placing a stumbling block before the blind, a reference to deceiving another person with bad advice.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

The Gemara continues with two points about the psychology of lending with interest:

Rabbi Shimon says: Those who lend with interest lose more than they gain. Moreover, they cause (it to seem that) Moses our teacher is a scholar and his Torah is true. And they say: “Had Moses our teacher known that there was a profit in the matter, he would not have written it (as a prohibition).”

The latter point is a euphemism: Rabbi Shimon is saying that those who lend with interest make a mockery of Moses and the Torah. Such a person will lose more than they gain because God sees what we do and will judge them for their actions. And someone so smitten with acquiring easy money from usurious exploitation has brazenly convinced themselves that even Moses would have excluded usury from the Torah had he known how much profit he could have made.

In his Talmud commentary Hiddushei Aggadot, Rabbi Shmuel Eidels puts an intriguing spin on Rabbi Shimon’s teaching, one that goes to the heart of the problem of lending with interest: “People who lend usuriously mistakenly believe that their borrowers will make a profit from the money they borrow; thus, the borrowers aren’t repaying their loans with interest, they’re just sharing their profit. This isn’t always the case: sometimes the borrowers make a profit from their use of the loan and sometimes they don’t.”

In other words, not only do usurious lenders lose more than they gain, the same is true for their borrowers. It’s easy to convince oneself that charging interest on a loan is simply how free markets operate and that it benefits everyone. This is especially the case when Jewish law, perhaps begrudgingly, gives us the legal means to deal with the realities of real-world business and to keep lenders motivated to assume the risks of lending. But as Rabbi Eidels implies, lender and borrower coexist in an uneasy, unequal power dynamic, especially when the borrower is in dire straits and is desperate for a loan to survive.

Exploiting the borrower’s vulnerability damages them. Deceiving oneself that such behavior is fine damages the lender, who becomes habituated to engaging in this kind of behavior. God is not interested in our acting this way. We are expected to do and be better.

Read all of Bava Metzia 75 on Sefaria.

This piece originally appeared in a My Jewish Learning Daf Yomi email newsletter sent on May 13th, 2024. If you are interested in receiving the newsletter, sign up here.