“What is the love of God that is appropriate? It is to love God with an exceedingly strong love until one’s soul is tied to the love of God. One should be in a continuous rapture, like a person who is ‘lovesick,’ whose thoughts cannot turn from his love for a particular woman. He is preoccupied with her at all times, whether he is sitting or standing, whether he is eating or drinking. Even more intense should the love of God be in the hearts of those who love him, possessing them always as we are commanded ‘with all your heart and with all your soul’ (Deuteronomy 6:5). This is what Solomon expressed allegorically ‘for I am sick with love’ (Song of Songs 2:5), and indeed, the entire Song of Songs is a parable for this concept.”—Maimonides, Laws of Repentance, 10:3

Although Maimonides adapts the language of the first paragraph of the Shema (Deuteronomy 6:4-8), known as v’ahavta — ואהבת, “and you shall love” — he is clearly echoing the language of the first paragraph. “When you sit in your house, when you walk on the way, when you lie down and when you rise up” (6:7).

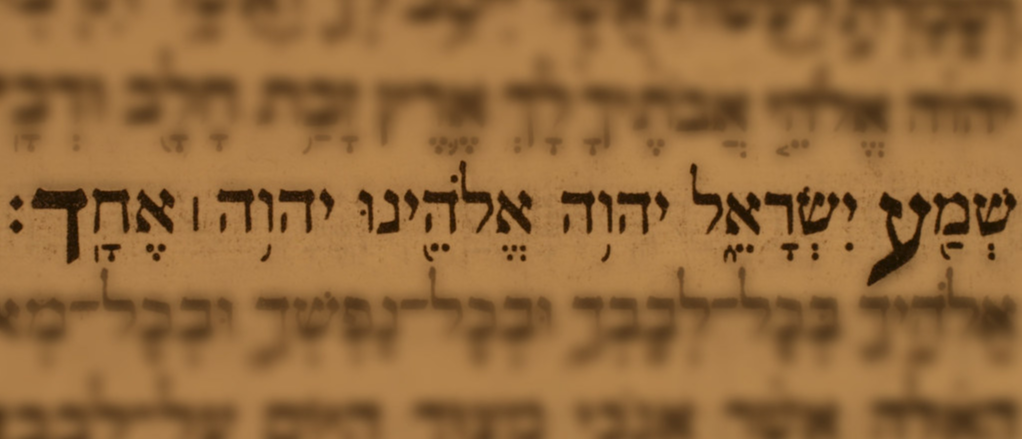

When one falls in love, this is what it is like. The object of one’s love is all there is; the love and the relationship create a complete unity of experience. A person in love wants to shout out “Do you hear! I am in love! This is the one!” That’s not too far from “Hear, O Israel, the Lord is our God, the Lord is one!” When one falls in love, one wants to learn everything about that person (“and you shall speak of them”), the conversations last all day and even through the night (“when you lie down and when you rise up”).

Sometimes people exchange personal items — it used to be a sweater or a pin or a handkerchief — which they keep with them in order to be tied to that person even when outside of the beloved’s physical presence. This, of course, recalls the tefillin, the leather boxes and straps that are worn each morning during prayers, but which, in earlier times, were worn by some pious Jews all day long. And photographs serve like mezuzot, the physical reminders of God with the words of the Shema, inside boxes placed on doorposts. When one first discovers God, when authentic spirituality is experienced, one is entirely enraptured by it, as one is when one first falls in love.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

After one falls in love, a relationship moves into a more serious mode. The initial rapture of infatuation moves toward learning about each other, really listening to each other, creating rules for the relationship, including general ones (such as, “Don’t have this kind of relationship with anyone else”) and specific ones (such as, “Don’t talk about my nose”). As long as the rules are observed, the relationship flourishes. When the rules are not observed, the ties that connect seem less bountiful, the relationship withers and falls apart.

Similarly, the second paragraph of the Shema (Deuteronomy 11:13-22) begins “If you will truly listen/understand/obey (אם שמע תשמעו) my mitzvot” and focuses on the need to pay attention in order to understand the “rules” of the human-divine relationship. Then the Shema presents the following condition: If you observe the commandments, God will send rain in the appropriate season; the fields will produce plenty of wine, grain, and oil; and you will eat and be satisfied. If you don’t observe the commandments, the rain will stop, the land will dry up, and you will starve.

The Bible was written for people who understood the cycle of rain. The rain literally and figuratively connects heaven and earth. The mitzvot are the commands that tie Israel to God and God to Israel. When they are observed, the relationship with God grows and produces fruit. When the mitzvot are ignored, the relationship withers away. The paragraph concludes with a view to the future. “[Do these things] so that your days upon the land be multiplied.” As this stage in a relationship matures, the couple begins to think about the long-term implications of their relationship.

The ultimate stage in this loving relationship is marriage and the declaration that the relationship will last. The marriage is marked by the use of a public sign and reminder, a wedding ring. The ring reminds the wearer of the marital covenant and is a sign to onlookers that the person is part of an eternal relationship. This is most crucial in avoiding “wandering hearts and eyes” through which a person prostitutes the relationship. In rabbinic terminology, the marital relationship is called kiddushin (sanctification) to indicate that the two are sanctified to each other.

In the final paragraph of the Shema (Numbers 15:37-41), Israel is commanded to make tzitzit (fringes) upon the corners of their garments as public signs and as reminders. The reference to the corner of the garment (kanaf) recalls the use of the language in the book of Ruth, where to come under the corner of one’s garment symbolizes the commitment to marry (Ruth 3:9). Nowadays, we take the tzitzit in our hand when reciting the Shema and kiss them. The tzitzit are designed to be public signs and also personal reminders “that you not go scouting-around after your heart, after your eyes which you go whoring after” (15:39, following Everett Fox’s translation). Do all of this, the Torah enjoins, “in order that you remember and do all of the commandments and thereby be sanctified (kedoshim) to your God” (והייתם קדשים לאלהיכם) (15:40).

Maimonides asks “What is the love that is appropriate for God?” His response is to love God as if you are falling in love, only more so. But humans don’t love that intensely all of the time. Judaism is not just for the moments of spiritual ecstasy or radical religious insight. Judaism is about Israel loving God for the long-term, and as the Shema teaches, that means learning the rules and making a long-term and public commitment.

Shema

Pronounced: shuh-MAH or SHMAH, Alternate Spellings: Sh'ma, Shma, Origin: Hebrew, the central prayer of Judaism, proclaiming God is one.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.

tzitzit

Pronounced: TZEET-tzeet, or TZIT-siss, Origin: Hebrew, fringes tied to the corners of a prayer shawl.