Today, the word “rabbi” usually conjures up the image of someone who leads a Jewish community, someone who sits up near the front of the synagogue, gives sermons and offers pastoral counseling and support. But in the time of the Talmud, rabbis were actually not the folks in charge of synagogues. They tended to hang out in houses of study — that’s where they learned and oftentimes even prayed. The synagogue was largely the purview of the rest of the Jewish community.

But sometimes, a rabbi would go out to teach the broader Jewish community. On today’s daf, we learn about one such rabbi, Levi, who left the study hall to teach and met some very incisive people.

They asked him: What is the halakhah for an armless woman, may she perform halitzah? What if a yevama spat blood (instead of saliva)? “But I will declare to you that which is inscribed in the writing of truth” (Daniel 10:21), if by inference, there is writing in Heaven that is not truth?

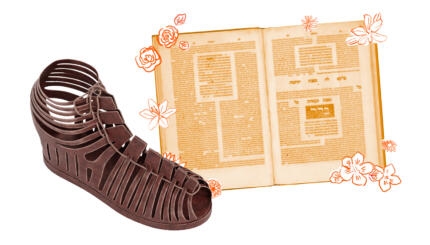

As we know, a yevama must remove the shoe of the yavam during halitzah, but can she do so with something other than her hand? Must the substance she spits be saliva? And if God specifies in the Book of Daniel that some writing is the writing of truth, does that mean that other parts of God’s writings are false?

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

The Gemara tells us that Levi didn’t know the answers to these questions. So he did what any rabbi would do in the days before Google — he went back to the study hall and asked his teachers. He learns that someone without arms can indeed perform halitzah, and that whatever substance comes out of the yevama’s mouth is valid in the performance of halitzah. And the phrase from Daniel about the “writing of truth”?

This is not difficult. Here it is referring to a sentence of judgment accompanied by an oath. There, a sentence of judgment that is not accompanied by an oath.

In other words, judgements that are not sealed with oaths can be overturned, and so are not considered permanent truth. Of course, the flip side of this interpretation is that judgments that are sealed with oaths are considered permanent and cannot be overturned. The Talmud goes on to limit when this interpretation applies: A sealed judgment cannot be overturned only when it is God’s judgment of an individual, but God’s judgment of the community as a whole can in fact be torn up and overturned. Really? Where do we get this idea?

The Gemara answers by citing this verse from Deuteronomy 4:7:

For what great nation is there, that has God so close unto them, as the Lord our God is whenever we call upon Him?

According to the Gemara, when the Jewish people collectively call upon God in prayer, God can and does overturn God’s own rulings. Prayer is a really powerful thing.

Let’s end by returning to Levi and to the people he meets in the villages. We know that the rabbis are profoundly committed to Torah and living halakhic lives. We we might then assume that people in the villages, far removed from the rabbinic centers, would be less knowledgeable and less invested. But today’s daf tells us that this assumption would be very wrong.

The people Levi meets are careful readers of Torah, and just as interested in the border cases as the rabbis themselves. And Levi is not the expert, coming to share knowledge with the ignorant — he himself doesn’t know the answer to their questions and must turn to his own teachers for support. It is only when Levi listens to the community’s questions and takes them seriously that his and their knowledge is expanded. We learn as much from our students as we do from our teachers.

Read all of Yevamot 105 on Sefaria.

This piece originally appeared in a My Jewish Learning Daf Yomi email newsletter sent on June 20th, 2022. If you are interested in receiving the newsletter, sign up here.