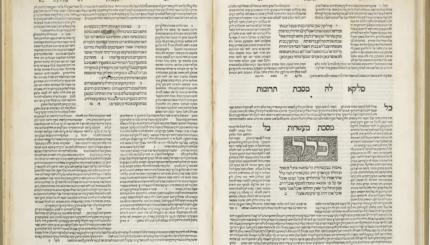

Yevamot (literally, ”levirate widows”) is the first and longest tractate of Seder Nashim, the order of the Talmud that discusses laws related to women, including marriage, divorce and the trial of the suspected adulteress.

When a man dies childless, the Torah prescribes that his widow should marry his brother so that the two of them can create a child who will carry on the deceased man’s name. This practice is called yibbum (levirate marriage) and the Torah’s only legal statement on it is found in Deuteronomy 25:5–10:

When brothers dwell together and one of them dies and leaves no offspring, the wife of the deceased shall not become that of another party, outside the family. Her husband’s brother shall unite with her: he shall take her as his wife and perform the levir’s duty. The first child that she bears shall be accounted to the dead brother, that his name may not be blotted out in Israel.

But if that party does not want to wed his brother’s widow, his brother’s widow shall appear before the elders in the gate and declare, “My husband’s brother refuses to establish a name in Israel for his brother; he will not perform the duty of a levir.”

The elders of his town shall then summon him and talk to him. If he insists, saying, “I do not want to take her,” his brother’s widow shall go up to him in the presence of the elders, pull the sandal off his foot, spit in his face, and make this declaration: “Thus shall be done to the man who will not build up his brother’s house!” And he shall go in Israel by the name of “the family of the unsandaled one.”

The Torah also contains two stories in which levirate marriage plays a role, those of Tamar (Genesis 38) and Ruth, though these are rarely referenced in this tractate. The statement in Deuteronomy, however, is subject to extensive rabbinic scrutiny.

Levirate marriage is an unusual mitzvah in several respects. It is the only halakhah that requires two people to marry. Further, ordinarily a man is forbidden to marry his sister-in-law, but levirate marriage renders that relationship not only permitted, but obligatory. Levirate marriage is also unusual insofar as a man can opt not to perform it. The ritual of halitzah, also detailed in the passage from Deuteronomy, releases the brother of the deceased from his obligation to marry the widow. (Some sages view halitzah as an alternative, and even perhaps preferable, mitzvah.) Levirate marriage is full marriage, yet it requires fewer rituals than ordinary marriage and has other stringencies attached. For instance, the sages require the couple to wait three months to ensure that the widow is not in fact pregnant by her dead husband.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Tractate Yevamot, focused on this exceptional form of marriage, may seem an unusual place to begin the discussions of women that will dominate this order of the Talmud. The reason for this is largely that the tractates in each order of Talmud are listed by length and Yevamot, which precisely because of its peculiarity raises scads of legal questions, is the longest. Readers will discover, however, that Yevamot raises many more broadly relevant subjects in rabbinic thought, including forbidden sexual relationships and conversion. It also introduces concerns that are relevant in any talmudic discussion of marriage, including the validity of the marriage, inheritance and laws of terumah (food tithes permitted only to priests and their families).

Yevamot contains 16 chapters and begins not with an explanation of the basics of levirate marriage, but with exceptional circumstances (in the case of chapter 1, women to whom levirate marriage does not apply). Because of the arcane nature of this tractate’s material (today, levirate marriage is vanishingly rare) and because a large amount of ink is devoted to exploring complex boundary cases, Yevamot is widely regarded as one of the most difficult tractates in the Talmud. Here is a brief survey of the contents of each chapter.

Chapter 1: Women to whom levirate marriage does not apply, including widows who are forbidden to their brothers-in-law because of the nature of their relationship and cases in which the deceased has multiple wives (only one of whom will enter into levirate marriage).

Chapter 2: Variants on a case in which a man is born after his older brother has died childless, such that the two brothers were never “in the world at the same time.”

Chapter 3: The legal ramifications of the levirate bond, by which the Talmud means the relationship between the deceased’s widow and his brother that is instantly created on his death but which is not a full halakhic marriage until the two have consummated their relationship.

Chapter 4: The four choices that face a yavam (man who is bound to his brother’s widow): halitzah (to dissolve the bond), levirate betrothal (ma’amar, a statement of intent to marry), intercourse (which effects the marriage) and divorce (delivering a get in order to dissolve the bond). Halitzah is the preferred way to dissolve the levirate bond, whereas intercourse is the proper way to fully cement it. Levirate betrothal affects a partial acquisition of the wife.

Chapter 5: Continued discussion of the ramifications of performing ma’amar or delivering a get, with the conclusion that neither is completely efficacious (nor completely ineffective), the first at cementing the levirate marriage and the second at completely dissolving the bond between the two parties.

Chapter 6: A discussion of intercourse as the primary means to effect levirate marriage gives way to a general discussion about forbidden sexual relations (punishable only when performed with intention). This chapter also discusses special rules pertaining to women who marry into the priesthood and the commandment to “be fruitful and multiply.” (Genesis 1:28)

Chapter 7: When a yevama (levirate bride) is entitled to terumah (tithes given to priests and their families).

Chapter 8: More halakhot of priests and when their families may partake of terumah. This chapter also discusses those who are forbidden to marry Israelites (first generation Ammonite and Moabite converts, mamzerim, etc.) and physical disabilities that can affect marital arrangements as well as less common genitalia (such as the case of the androgynos and tumtum).

Chapter 9: Women who are, for various reasons, forbidden to their yavam or husband and therefore halitzah or divorce is required. More on the laws of terumah in the case of the death of a woman’s husband.

Chapter 10: What happens in the case of a man whose reported death turns out to be false and his wife has already remarried. Cases in which the yavam is a minor.

Chapter 11: Marriage to women who were raped or seduced by relatives. How conversion affects forbidden sexual relationships. Exploration of doubtful familial relations (such as babies whose father or mother is unknown), including how this affects the commandment to honor one’s parents.

Chapter 12: The procedure of halitzah: Who are the elders? What sandals are effective? What words must be spoken?

Chapter 13: Rules surrounding the engagement or marriage of a minor girl who, upon coming of age, refuses her fiance. This kind of marriage can be dissolved by the woman without a get. Likewise, girls who became yevamot before they reached the age of majority.

Chapter 14: Marriage to people with disabilities.

Chapter 15: More on what happens when a woman remarries based on false testimony that her husband has died. Rules surrounding the testimony that a husband has died.

Chapter 16: More on the testimony required to prove the death of a husband.