Commentary on Parashat Chukat, Numbers 19:1-22:1

- The laws of the red heifer to purify a person who has had contact with a corpse are given. (Numbers 19:1–22)

- The people arrive at the wilderness of Zin. Miriam dies and is buried there. (Numbers 20:1)

- The people complain that they have no water. Moses strikes the rock to get water for them. God tells Moses and Aaron they will not enter the Land of Israel. (Numbers 20:2–13)

- The king of Edom refuses to let the Children of Israel pass through his land. After Aaron’s priestly garments are given to his son Eleazer, Aaron dies. (Numbers 20:14–29)

- After they are punished for complaining about the lack of bread and water, the Israelites repent and are victorious in battle against the Amorites and the people of Bashan, whose lands they capture. (Numbers 21:4–22:1)

Focal Point

Miriam died there and was buried there. The community was without water, and they joined against Moses and Aaron…

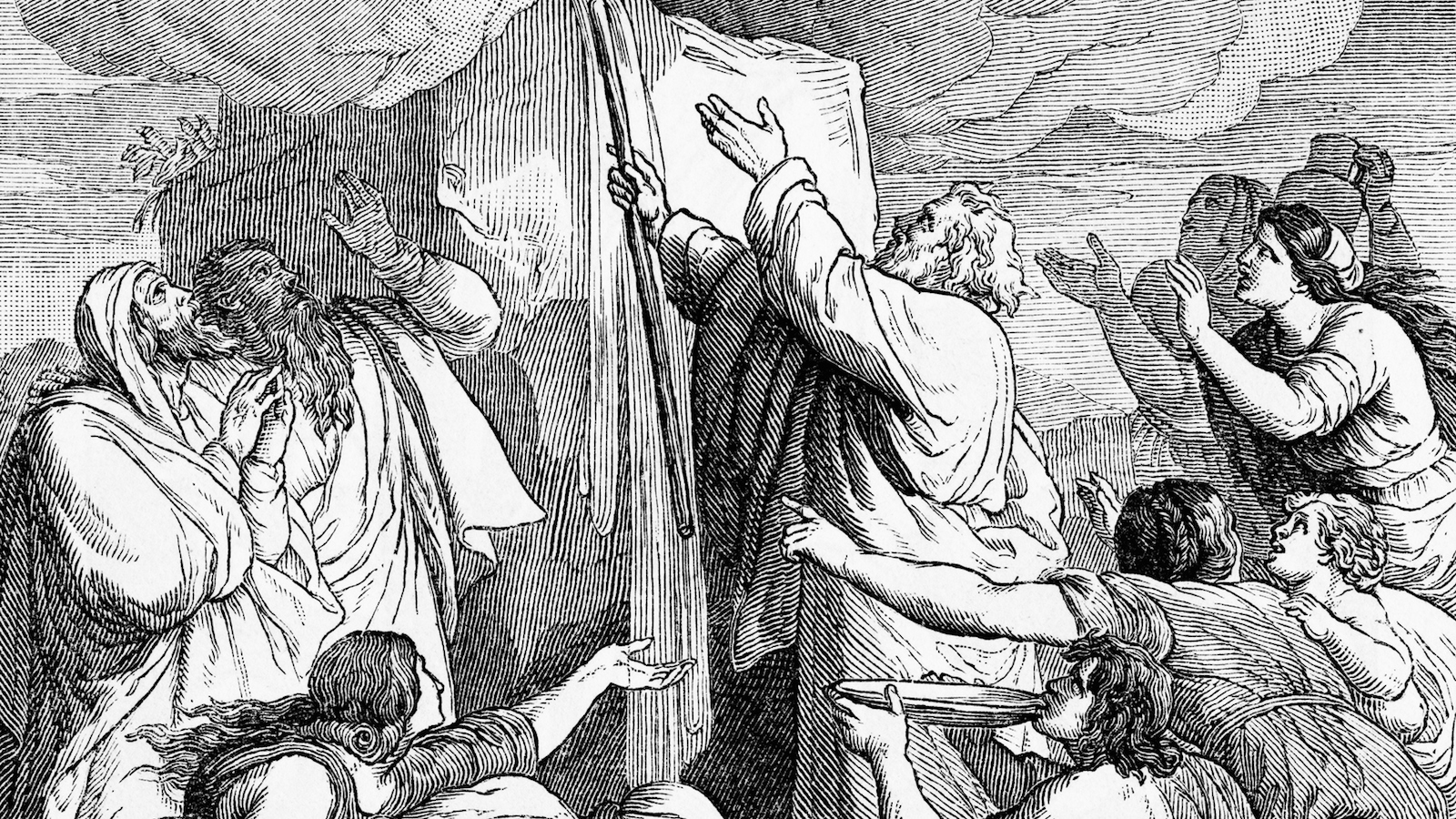

Moses and Aaron came away from the congregation to the entrance of the Tent of Meeting and fell on their faces. The Presence of Adonai appeared to them, and Adonai spoke to Moses, saying, “You and your brother Aaron take the rod and assemble the community, and before their very eyes order the rock to yield its water. Thus you shall produce water for them from the rock and provide drink for the congregation and their beasts.”

Moses took the rod from before Adonai, as God had commanded him. Moses and Aaron assembled the congregation in front of the rock; and he said to them, “Listen, you rebels, shall we get water for you out of this rock?” And Moses raised his hand and struck the rock twice with his rod. Out came copious water, and the community and their beasts drank.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

But Adonai said to Moses and Aaron, “Because you did not trust Me enough to affirm My sanctity in the sight of the Israelite people, therefore you shall not lead this congregation into the land that I have given them.” Those are the Waters of Meribah — meaning that the Israelites quarreled with Adonai — through which God affirmed His sanctity. (Numbers 20:1–13)

Your Guide

Does the punishment meted out to Moses and Aaron fit the “crime?” If Moses and Aaron had sinned so egregiously, why did God nonetheless provide the people with ample water?

This incident takes place against a backdrop of continued devolution, specifically after the death of Miriam. What significance might be accorded to the absence of an official mourning period for Miriam? What do you think of the following teaching by Rabbi Moshe Alsheich (quoted in The Stone Edition Chumash, p. 843): “Because they [the Israelites] did not shed tears over the loss of Miriam, the source of their water dried up?”

Moses and Aaron’s sin “constitutes the climax of a series of rebellions: first by the people, then by the Levites and chieftains, and finally by the leaders, Moses and Aaron” (The JPS Torah Commentary: Numbers, p. 163). What lesson in political and personal dynamics is being offered here?

By the Way…

For had you spoken to the rock [rather than struck it] and it would have brought forth water, I would have been sanctified before the eyes of the assembly. (Rashi on Numbers 20:12)

His whole sin lay in erring on the side of anger and deviating from the mean of patience when he used the expression “you rebels.” (Maimonides, Sh’monah P’rakim 4:5)

At Meribah of Kadesh, the rock of “strife and holiness,” the ancient leadership was shattered. It broke because a new age demanded new vision, new faith, and undiminished capacity to sanctify the God of Israel to the people of Israel. If the Torah implies sin on the part of Moses and Aaron, it can only be the sin of failure: For leaders are always held responsible for the performance of those they lead. Both Moses and Aaron apparently considered the divine judgment to be just and knew it to be irreversible. Aaron never raised his voice concerning it, and Moses did it once and then ever so briefly (Deuteronomy 3:23-25). (W. Gunther Plaut, The Torah: A Modern Commentary, p. 1,156)

The Holy One, blessed be God, said to Moses, “The first offense that you committed was a private matter between you and Me. Now, however, that it was done in the presence of the public, it is impossible to overlook it, as it says [Numbers 20:12], ‘because you did not trust Me enough to affirm My sanctity in the sight of the Israelite people.'” (Midrash Rabbah 19:10)

The sin consisted of their saying, “Are we to bring you water out of this rock?” They should not have said “we” but rather “Shall the Eternal bring you water out of this rock?” (Rabbeinu Hananel on Numbers 20:10, cited by Nachmanides)

Pagan magic may or may not involve a manual act, but it always involves the use of words…. It is a central element of Moses’ prophetic role that he sever Israel from idolatrous seductions. To this end, God helps Moses by showing Israel authenticating “signs” of His power: miracles. But to ensure that Israel understands that it originates in divine will and not as a coincidence of nature, God repeatedly instructs Moses to describe the miracle in advance and to designate the precise moment of its occurrence through a specific manual act. (Jacob Milgrom, The JPS Torah Commentary: Numbers, pp. 452-453)

Your Guide

In Exodus 17:6, Moses, following God’s order, had successfully provided water for the community by striking a rock. In this week’s parsha, Moses is told to order the rock, not strike it twice. What is the moral lesson here?

Is it fair or appropriate to find Moses deficient in anger management? What was God’s intent in this incident? Why didn’t Moses and Aaron have an opportunity to rehabilitate themselves? How many strikes were Moses and Aaron actually allowed?

How should a leader’s public and private behavior be judged? What criteria should be employed?

Look at the following biblical verses: Numbers 20:12, Numbers 20:24, Numbers 27:14; Deuteronomy 1:37, Deuteronomy 3:25-26, Deuteronomy 4:21, Deuteronomy 32:50-52; and Psalms 106:32-33. According to the biblical writers, what did Moses and Aaron do to deserve their severe punishment?

Commentary

Strike one. Aaron’s two sons Nadab and Abihu die in the Sanctuary while performing a mysterious and unwelcome ritual, and Aaron is informed, “Through those near to Me I show Myself holy, / And assert My authority before all the people” (Leviticus 10:3). But that is not the end of the story. Indicating their discomfort regarding the ambiguous rationale for that tragedy, the writers of the Torah repeatedly return to it (Leviticus 16:1; Numbers 3:4, 26:61).

Strike two. Then in the absence of a clear justification for the sentences imposed on Moses and Aaron, the Torah’s narrative proffers the same conclusion stated in Leviticus 10:3: “Judaism teaches that the greater the man [or woman], the stricter the standard by which he [or she] is judged” (S. R. Hirsch in The Pentateuch and Haftorahs, edited by J. H. Hertz, p. 656; also see Everett Fox, The Five Books of Moses, p. 754).

Yet perhaps the fact that Moses and Aaron received sentences is the lesson itself, namely, that we are not always allowed three strikes. Sometimes, the punishment is final. Amidst life’s uncertainties, we cannot satisfactorily understand, let alone justify, the ultimate morality in every occurrence. Still, by our endeavor to continually recount and reconsider the past, we affirm sacred processes and quests: We are kept in the game.

Reprinted with permission from the Union for Reform Judaism.

Moshe

Pronounced: moe-SHEH, Origin: Hebrew, Moses, whom God chooses to lead the Jews out of Egypt.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.