Commentary on Parashat Vayakhel, Exodus 35:1-38:20; Numbers 19:1-22

The talmudic phrase bitul Torah, literally the “cancellation of Torah,” refers to the time one spends occupied with the world at large, away from Jewish text study. Chol, literally “profane,” refers to the six days of the week before Shabbat. Such language suggests that religious life takes place only within the temporal boundaries of ritual.

This notion is problematic and spiritually impoverished. Religious life is not a series of proscribed acts separated by spans of mundanity. To the deeply religious person, spiritual life is continuous. Moments of ritual dust off the soul and propel the individual into the following hours with renewed awareness and intention.

Parashat Vayakhel reminds us that religiosity transcends ritual. Moses addresses the whole Israelite community for the first time since his dramatic return from Mount Sinai. He briefly commands the nation to observe Shabbat (Exodus 35:2-3) and then launches into a long, detailed speech about the construction of the Mishkan.

The rest of Parashat Vayakhel, and much of Parshat Pekudei, are devoted to this grand project and document the overwhelming generosity of the Israelite community to complete it. Moses’ short instruction about the holy seventh day virtually dissolves in the details of construction–building, melting, welding, and other acts that are forbidden on Shabbat. Just as the vast majority of life occurs outside of ritual acts, the vast majority of this parsahah focuses on the activities of chol.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

The Mitzvah to Work

Moses suggests that our work in the world before and after Shabbat is no less important than Shabbat itself. “Six days you shall do work,” he commands, “and on the seventh day you shall have a Shabbat of complete rest” (Exodus 35:2).

Thus, the first mitzvah that Moses articulates after Mount Sinai is that we should engage in work for six-sevenths of every week. Insofar as Shabbat is a call for rest on Saturdays, it is also a call for action on all other days. From this perspective, the true observance of Shabbat is an ever-flowing, lifelong affair that usually consists of working.

This is not to say that Parashat Vayakhel disregards or undervalues religious ritual itself. Moses’ few words about the observance of Shabbat could hardly be more emphatic. “Whoever does any work [melachah] on it [Shabbat] shall die,” (Exodus 35:2) he warns. According to the medieval commentator Rashi, Moses prefaces his speech about the Mishkan with a warning about Shabbat in order to remind the Israelites that the Mishkan does not supersede Shabbat.

Lessons from the Mishkan

The construction of the Mishkan has traditionally been regarded as an illustration of what we should not do on Shabbat. Indeed, the Rabbis derived the 39 prohibited actions on Shabbat directly from the 39 acts of labor involved in the creation of the Mishkan.

However, we can also view this principle from the opposite angle. While the construction of the Mishkan demonstrates inversely what Shabbat should not look like, it also reveals a direct prescription for our engagement during the rest of the week.

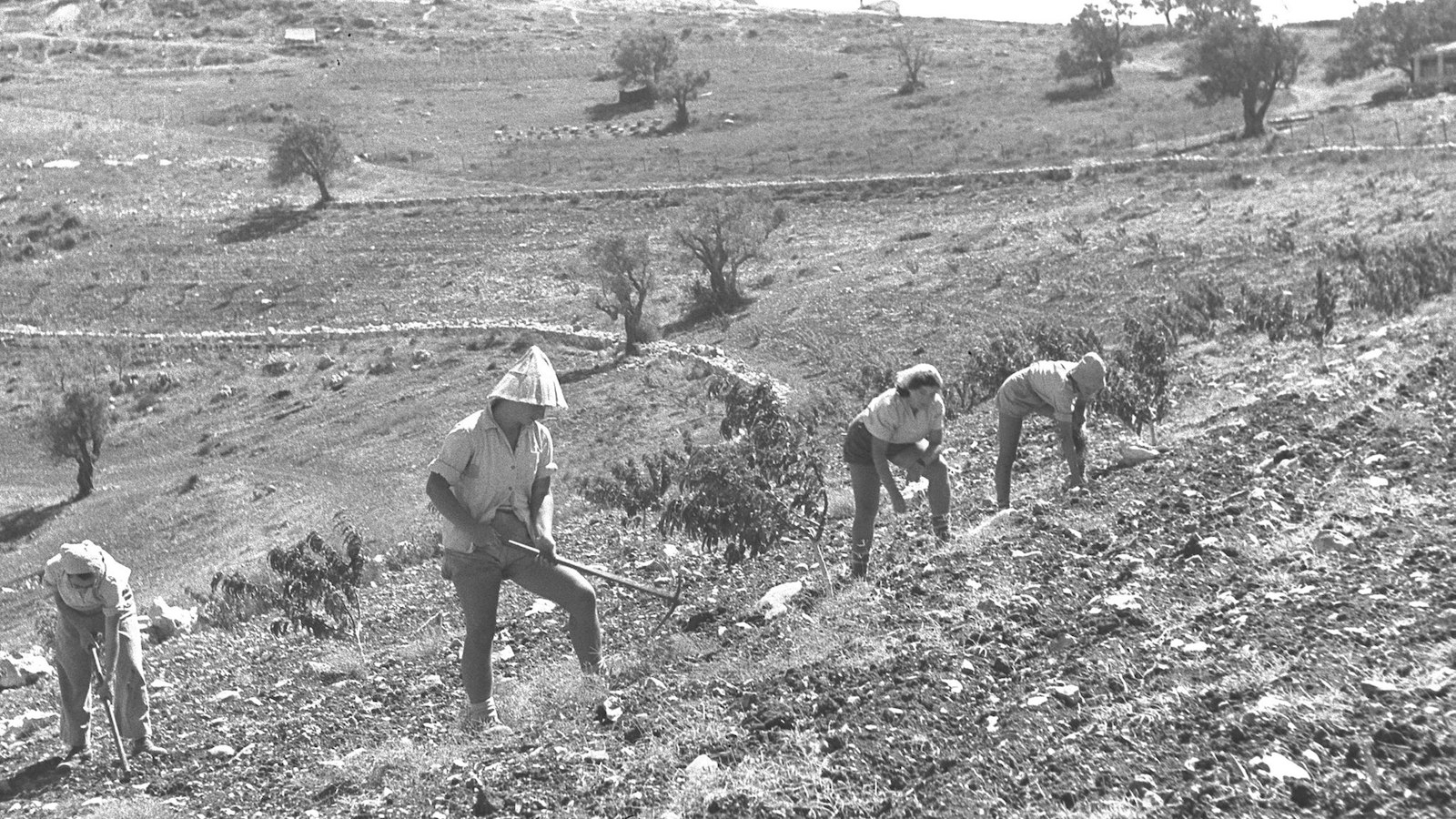

According to Midrash, the Mishkan is a microcosm of the whole world. Like the nation who built the Mishkan as a dwelling place for the Divine, we must work to make the world worthy of that Presence. The levels of scrutiny, care and “voluntary-heartedness” (Exodus 35:5) that define the building process in Vayakhel and Pekudei beckon us to devote equally high levels of mindfulness and spirit to our own melachah (work) at all times. We must take our work during the week very seriously.

Every act of melachah–that which we do in homes and offices, public squares and private spaces–changes the world in a constructive or destructive way.

When we purchase imported goods, what types of labor are we supporting overseas? For those of us employed outside our homes, how does our professional work–and that of our companies and organizations–hurt or help people globally? How do we use our money, time, and physical selves to pursue justice in the world?

When we speak with children, when we are at home and on our ways, when we lie down and when we rise up, do we ask ourselves which nails, knots, clasps, and sheets we will contribute to the Mishkan of the world today? These day-to-day activities are what make our world a dwelling place for the Divine.

Shabbat is important, yet our behavior during the other six days is no less a part of religious life. Shabbat is when we step back and appreciate the created world. Chol is when we step up and participate in creating that world. Piety is not only a reflection of what we observe, but also of what we build.

Provided by American Jewish World Service, pursuing global justice through grassroots change.

mitzvah

Pronounced: MITZ-vuh or meetz-VAH, Origin: Hebrew, commandment, also used to mean good deed.

Shabbat

Pronounced: shuh-BAHT or shah-BAHT, Origin: Hebrew, the Sabbath, from sundown Friday to sundown Saturday.

Midrash

Pronounced: MIDD-rash, Origin: Hebrew, the process of interpretation by which the rabbis filled in “gaps” found in the Torah.