Now that the High Holidays are over, you may be looking for new ways to stay spiritually awake. One of my favorite practices is walking a labyrinth.

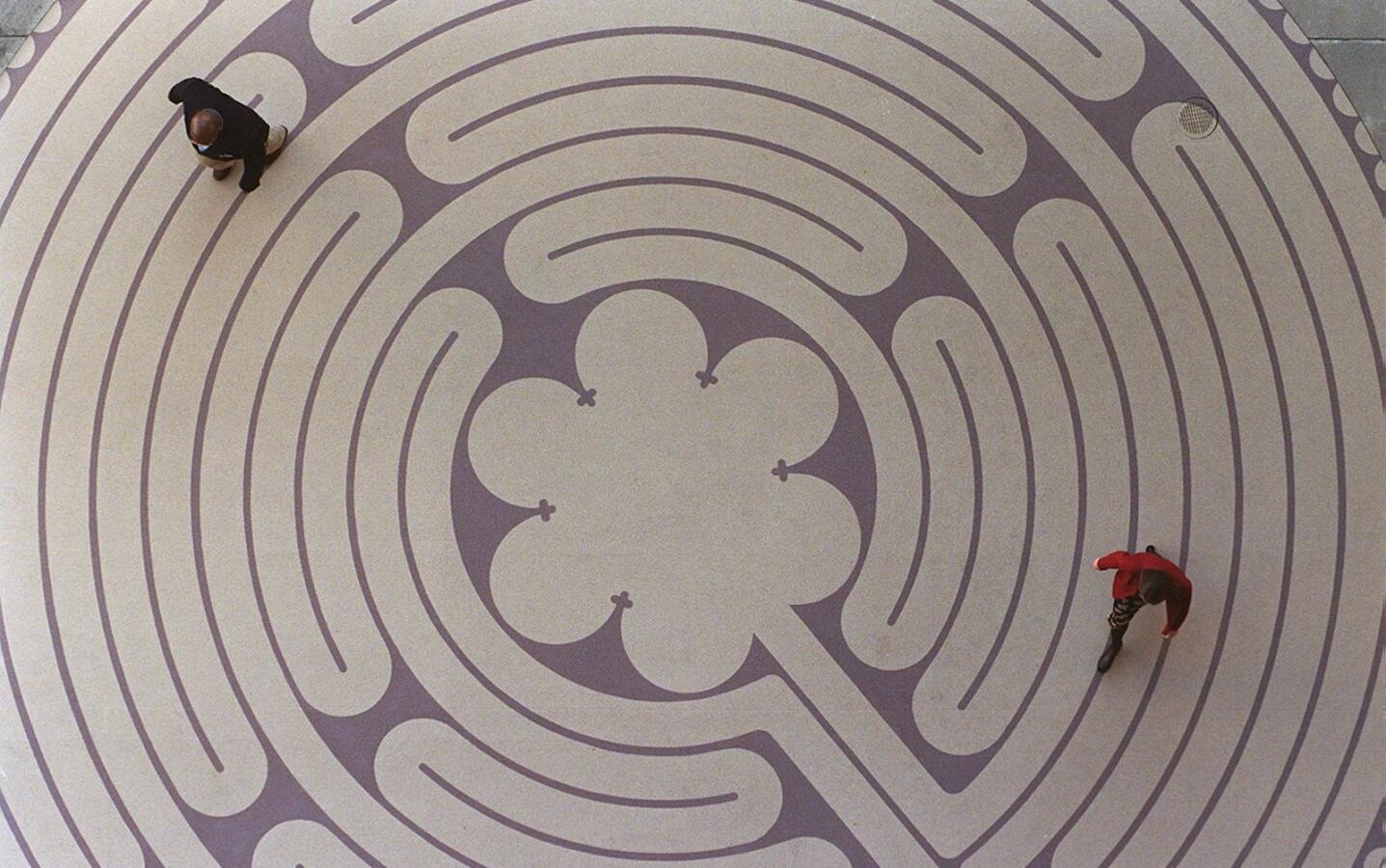

A labyrinth is a maze-like path that winds through several circuits toward a sacred center. But unlike a maze, a labyrinth has only one path, leading to one center at its heart. The term comes from the Greek labyrinthos, but the structural form can be found from Ireland to Turkey and India.

I’ve walked labyrinths in Ireland and California, at the National Cathedral in Washington, and at retreat centers. I’ve built labyrinths for Yom Kippur, to embody the journey of teshuvah (return or repentance), and for Tisha B’Av, as a meditation on losing and regaining a sense of sacred space. When I watch people enter a labyrinth and navigate its coils, it’s clear to me something unique and powerful is unfolding. The labyrinth is a pilgrimage practice that can happen anywhere, a way of making a journey to the heart.

Jews have long related to the labyrinth as an experience of journey or pilgrimage. We find the labyrinth as an illustration in Jewish texts, including the Taj Torah, a 15th-century Hebrew manuscript from Yemen, which features the six-circuit Jericho labyrinth depicting the Israelites conquering the city across a labyrinthine path. The Farhi Bible, written in Provence in the 14th century, depicts a similar labyrinth. That these images are found in Jewish texts suggest they are not only decorative, but meant to be sacred.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

We might even imagine that reading the Torah is itself a winding journey along a labyrinth. Since sacred text is a crucial way in to Jewish spiritual practice, it makes sense that we find labyrinths in texts. Yet embodied journey is a core Jewish practice. From ancient Israel to Morocco to Eastern Europe, Jews have used the practice of pilgrimage — to the Temple, or to holy tombs — as a way of showing devotion or to pray for a deep desire.

We could even see the High Holiday season out of which we have just emerged as a kind of labyrinth in time, spiraling in toward the sacred center of Yom Kippur and then out again into the world with the festival of Sukkot. At this moment in the Jewish calendar, it’s as if we’ve just left a huge labyrinth and are at the exit, integrating the insights we discovered.

Jews aren’t strangers to journeys of the spirit. Sefer Yetzirah (the “Book of Creation”), an ancient work of Jewish mysticism, speaks of “running and returning,” a phrase which can refer to the internal traveling we do when trying to connect to spirit. The heart “runs,” in the words of Sefer Yetzirah, and we “return to the place” — back to presence, to focus, to the Divine. We may experience an internal shift as movement, as arrival or return.

The center of the labyrinth may seem like the point, but for me, it’s often the return to the entrance, after the journey in and out, that is most affecting. That moment is the embodiment of running and returning — following the thread into the depths, and then coming back to ordinary life bearing the trace of a sacred encounter. A labyrinthine image of concentric sefirot, the 10 divine emanations enumerated by Jewish mysticism, is found in a 14th century commentary on Sefer Yetzirah, suggesting I’m not the only one who has made a connection between the labyrinth and the running and returning of the Jewish mystics.

There’s something about making a journey with the body that invites us to open the heart and mind. The Talmud seems to agree. In Tractate Rosh Hashanah, we find a teaching that one who changes their place, just like one who does teshuvah, can improve their destiny. But don’t take my word for it. Commenting on the practice of walking a labyrinth, Rabbi Laura Duhan Kaplan writes: “Don’t bother trying to read about it … Just walk, and see which metaphors come alive for you.”

Traveling a labyrinth is a way to bring alive the pilgrimage practices and mystical ascents of our ancestors, no matter where we are or what sacred spaces we have access to. I recommend it — and, if its popularity across space, time, and civilizations is any indication, you’ll likely meet a few fellow travelers along the way.

This article initially appeared in My Jewish Learning’s Shabbat newsletter Recharge on Oct. 16, 2021. To sign up to receive Recharge each week in your inbox, click here.