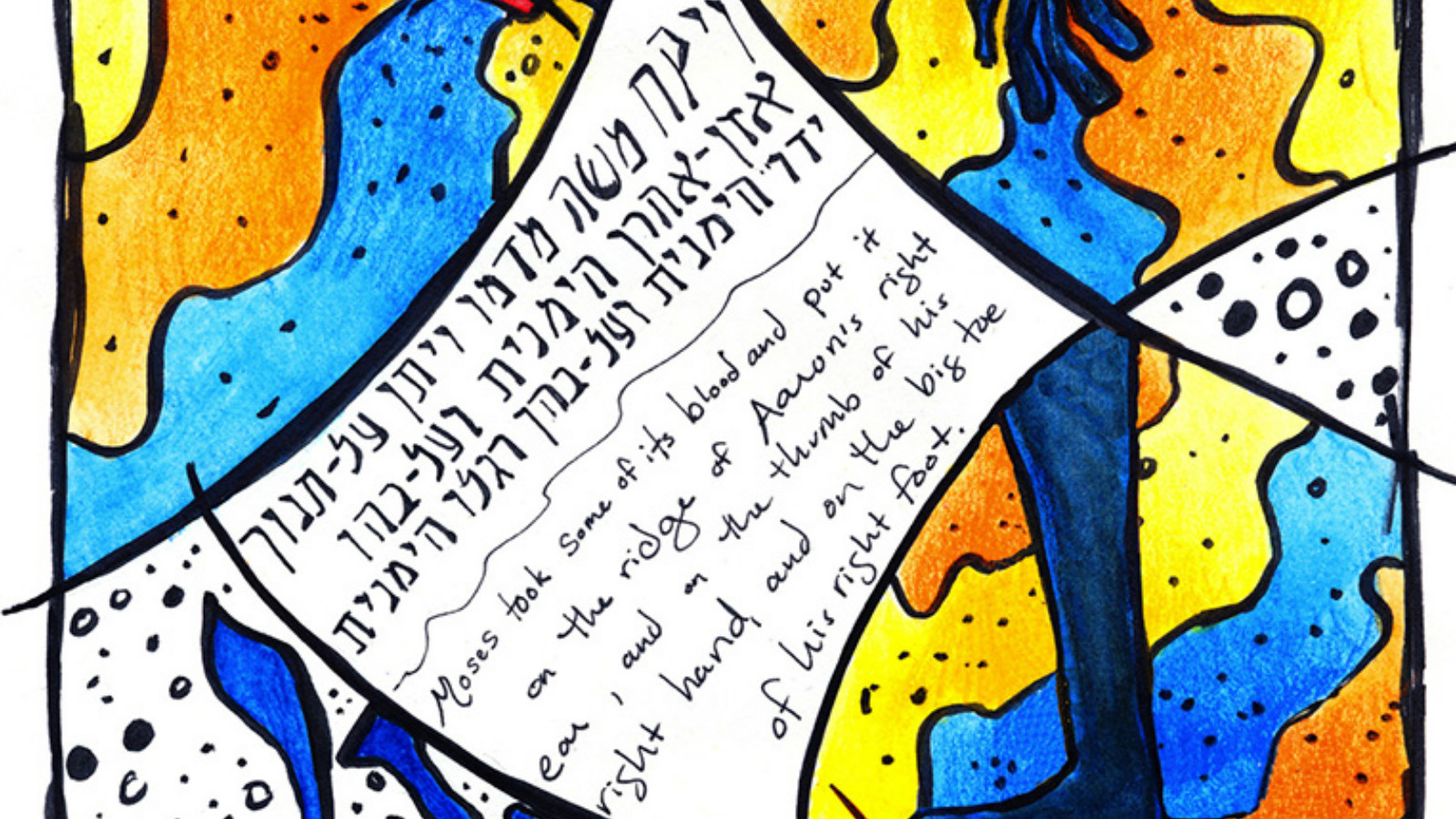

Commentary on Parashat Tzav, Leviticus 6:1-8:36

Sourdough. French baguettes. Olive focaccia. Pita with za’atar. Rosemary ciabatta.

Bread is a comfort food, in both normal times and times of challenge. During moments of stress and uncertainty we often see baking frenzies take hold, with shortages of yeast on supermarket shelves and the neighborly swapping of sourdough starters. When the world feels disorienting, pastry chefs orchestrate live brioche bake-offs on Instagram and renowned bakers offer tips on how to braid a six-strand challah.

Why the obsession with bread?

A unique law related to the korban todah in Parashat Tzav may offer an explanation. The korban todah was a sacrificial offering of gratitude brought in the ancient Temple. Unlike other sacrifices that were brought to atone for sin or to mark religious occasions, the korban todah was an offering of thanksgiving, brought in appreciation for recovering from illness or surviving a perilous journey.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

The laws of the korban todah include an addition not found in the requirements of other sacrifices — bread, a lot of it. We are told in Leviticus 7:12 that one who brings a thanksgiving offering must do so with ten loaves each of four types of bread – unleavened loaves mingled with oil, unleavened wafers spread with oil, loaves of soaked fine flour with oil, and loaves of leavened bread. A total of 40 loaves.

Why does the Torah demand such a large quantity of bread accompany this sacrifice and not the others?

Before we answer that question, let’s explore another unique dimension of the bread that accompanies the korban todah. In general, there is a prohibition against using leaven in all grain offerings that were brought in the Temple. The prohibition appears twice earlier in Leviticus, when the Torah instructs that all grain-based offerings be made with unleavened matzah. Yet even after delineating this prohibition, the Torah commands that leavened bread must be brought with the korban todah.

Why is this the case?

The answer rests upon the symbolic nature of both of these grain-based products. Dough that has risen is a delicacy, the result of a lengthy process and a series of steps that require accuracy and time. When yeast is added to flour and water and the dough rises, the result is a robust and textured culinary delight. There is accomplishment in the process. When the oven is opened and perfectly shaped loaves are removed, the feelings of pride and wholeness are palpable.

This is the reason why when we offer a korban todah, we do so with leavened bread. It represents a sense of completion and fulfillment for which we express our gratitude. Matzah, on the other hand, symbolizes humility, imperfection, and yearning. It is the bread of the poor. The preparation process is stopped midway, an expression of incompleteness. It is for this reason that matzah normally accompanies our sacrifices to God. Standing before a force larger than ourselves, matzah expresses the humility and dependency we feel as we walk the world.

With the korban todah, we approach God in a different spiritual state. We bring it when we feel whole, confident, safe, secure and complete. In this way, the sacrificial process gives us room to explore the many different dimensions of human experience. The korban todah is the fullest expression of a life that is whole.

Read this Torah portion, Leviticus 6:1 – 8:36 on Sefaria

Sign up for our “Guide to Torah Study” email series and we’ll guide you through everything you need to know, from explanations of the major texts to commentaries to learning methods and more.

Subscribe to A Daily Dose of Talmud: Daf Yomi for Everyone — every day, you’ll receive an email that offers an insight from each page of the current tractate of the Talmud. Join us!

About the Author: Shira Hecht-Koller is a teacher, writer and educational entrepreneur, currently the director of education for 929 English, a global platform for the study of the Hebrew Bible.