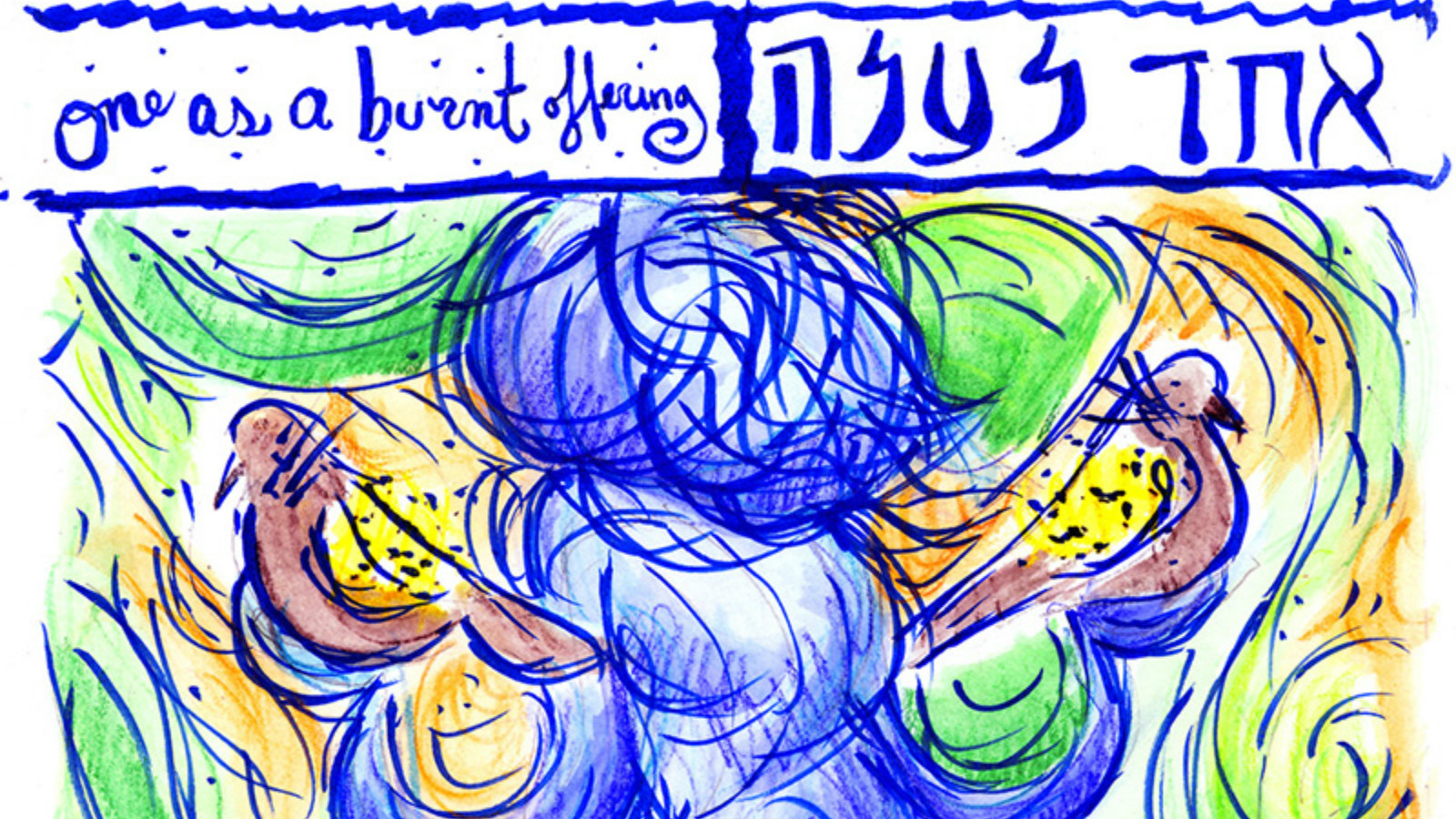

Commentary on Parashat Tazria-Metzora, Leviticus 12:1-15:33

In Parashat Tazria-Metzorah, God commands Moses and Aaron that anyone who suffers from skin ailments needs to be seen by a kohen, a priest, to diagnose the condition. Depending on what he sees, the kohen may pronounce the person pure, quarantine them for a time or declare it a case of tzaraat, a mysterious physical and spiritual ailment, often mistranslated as leprosy. Strangely, to our way of thinking about disease, tzaraat can affect not only a person’s skin, but also their clothes, items or home. If the priest makes the diagnosis of tzaraat, the affected person is isolated outside the camp until they recover and then they undergo a ritual of purification.

Tzaraat is difficult to understand, and it can also be difficult for us to derive meaning from the texts about it. Years ago, my synagogue invited a local dermatologist to offer the d’var torah for Parashat Tazria-Metzora in the hopes of gaining insight about the physical ailment outlined in the parashah. The dermatologist shared an article in a medical journal in which someone tried to identify the illness of tzaraat with any contemporary skin disease. Disappointingly, the article concluded that there is no single diagnosis that fits the biblical description.

How did our sages treat this material? Turning to traditional sources, we find that they were less interested in physical symptoms than the spiritual causes of the ailment. The Bible offers several examples of individuals cursed with the malady for a variety of misdeeds — perhaps most famously Miriam for critiquing Moses for his marriage to a non-Israelite — but the rabbis generally connected it to motzi shem ra, spreading malicious gossip about others (Babylonian Talmud, Arachin 16). Similarly, Maimonides, the great medieval rabbi and physician, insisted that tzaraat was a spiritual ailment:

Tzaraat is a collective term including many afflictions that do not resemble each other … This change that affects clothes and houses which the Torah described with the general term of tzaraat is not a natural occurrence. Instead it is a sign and a wonder prevalent among the Jewish people to warn them against lashon hara (“evil speech”) … requiring the sufferer to be isolated and for it to be made known that he must remain alone so that he will not be involved in the talk of the wicked which is folly. (Mishneh Torah, Defilement by Leprosy, 16:10)

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Our sages transformed the plain sense of a mysterious skin ailment into a springboard for a different topic altogether: avoiding the malignant sins of gossip and slander.

I believe there are other meanings to be discovered in the Torah’s description of tzaraat as well. One way to find meaning is to read with attunement to the feelings of the person diagnosed. Like our ancient ancestors, we moderns deal with uncertainty over health and illness, even if we are consulting a physician instead of a kohen, or WebMD instead of Leviticus. We, too, worry about our health, longevity, fertility and other areas of biological life that are outside our control. Too often, we find ourselves avoiding people with illness, and subconsciously blaming them for contributing to their own illness, which the rabbinic association of tzaraat with slander may have reinforced for us. A congregant who is a surgeon chose this portion for her adult bat mitzvah and spoke poignantly about the meaning that she got from caring for individuals who had stigmatized diseases that made them like modern day “lepers,” placed “outside the camp” or society.

Tazria-Metzorah highlights the power of diagnosis. The Torah says that remedies for the ailment can happen only after the diagnosis is made by a priest. The power of this process is more than practical, it’s also psychological. In an interview with the American Medical Association journal of medical ethics, Catherine Belling, Ph.D., spoke about the narrative power of diagnosis, saying, “To be diagnosed is to be known. To have a label put on oneself, but also to have a truth told about oneself …”

Diagnosis of physical or mental disorders can be devastating to some, but to others it is freeing. It can be the key to gaining access to resources and a path toward better health but, more importantly, to making sense of a difficult experience.

We can study Tazria-Metzora to try to find the simple scientific meaning of an ancient malady, and we can follow the sages and reinterpret it as a warning to avoid gossip and slander. I think our study gains even more meaning when we open ourselves up to what these portions evoke for us — for me, the power of diagnosis. That process connects us to the lives of generations past and to the universal human condition.