In this week’s Torah portion, Sarah dies in a place called Kiryat Arba, which the Torah identifies as Hebron, and Abraham sets about finding a burial plot for her. The inhabitants of ancient Israel often buried their dead in small caves, and these plots were often family or clan owned, passed down over the generations. As an immigrant, Abraham did not have one of his own and would need to petition the local Hittites for access, which he does, telling them: “I am a resident alien among you; sell me a burial site among you, that I may remove my dead for burial.”

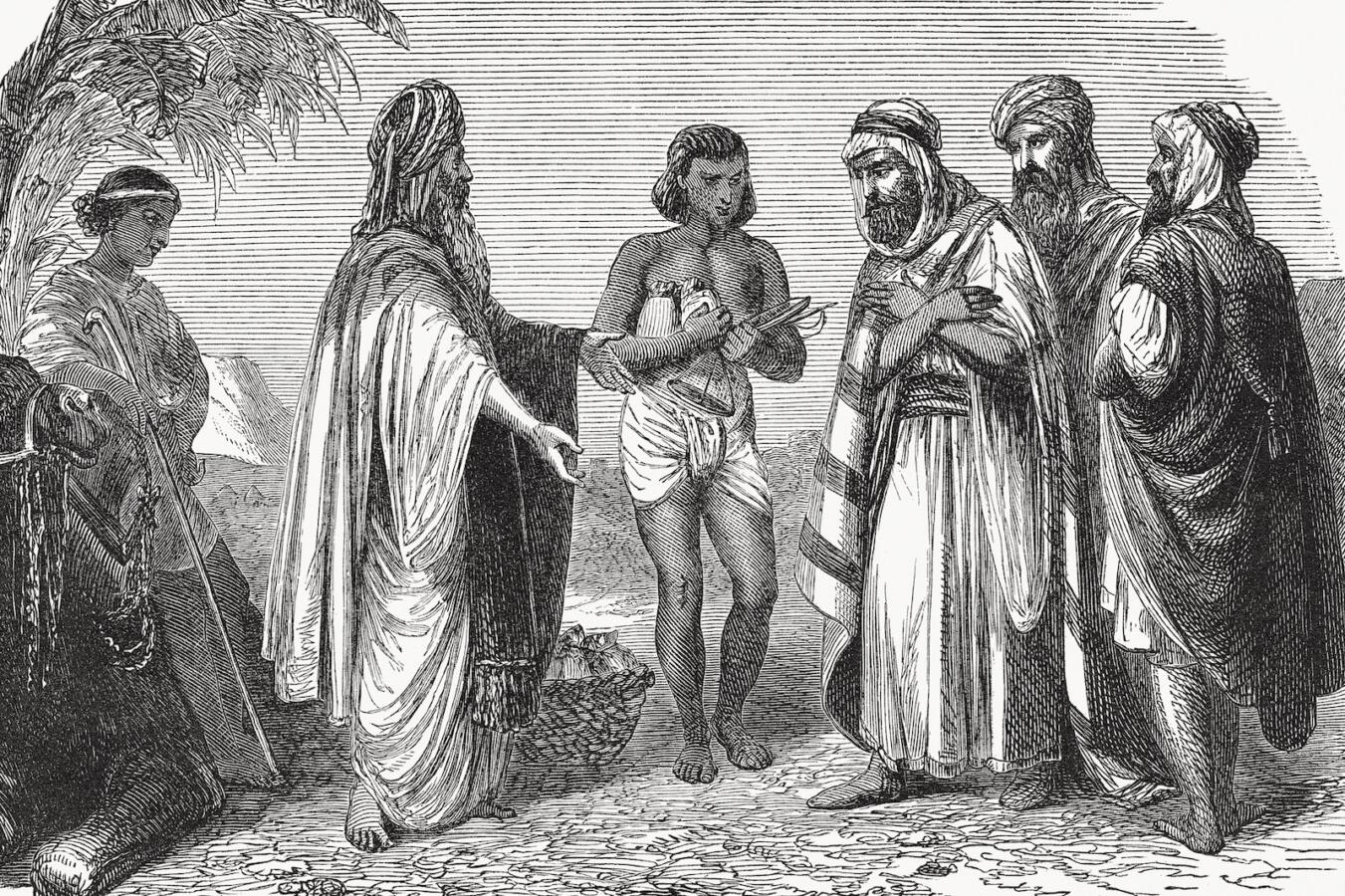

Abraham’s power and importance are clear from the response. The people tell him that he is God’s elect and they invite him to bury Sarah in one of the choicest burial spots. But Abraham does not take the people up on this offer, asking instead to speak with a man named Ephron son of Tzohar, who owns a cave that Abraham wishes to purchase as a family tomb. Ephron also tells him that money is not necessary, but Abraham insists on paying full price, which ends up being exorbitant, since Ephron sells him not just the cave but the whole field.

The story of Abraham buying Sarah’s tomb is part of what biblical scholars refer to as the Priestly (or P) text, which many believe was composed (or at least finalized) during the Second Temple period, during the years of Persian rule between the sixth and fourth centuries BCE. One of the major changes between the end of the First Temple period and the Second Temple Period, when the Judeans returned to the land and reestablished the political entity of Judea, was that the Edomites had moved into the mostly abandoned region of what had been southern Judah. Thus, when the Judeans returned, they found Hebron inhabited by Edomites. The returnees established their own presence in the region with the founding of Kiryat Arba, slightly to the north of Hebron, and thus the two peoples lived cheek by jowl, each seeing themselves as the legitimate natives of the land.

Read in this context, the story takes on symbolic import. Abraham represents the Judeans, who now find themselves outnumbered, a minority in their ancestral land. The Hittites are the Edomites, who for all intents and purposes control the great city of Hebron. What should the attitude of the returnees be to the new dominant population of the region?

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

The Torah’s answer is: respect. Abraham refuses to take gifts given either out of fear — Abraham does have a private army — or as part of an implied quid pro quo. Instead, he pays full value without complaint, even if centuries of readers suspect he was overcharged. Abraham’s goal in paying is twofold: first, to make it clear to all involved that he is no thief; and second, to build rapport with his neighbors.

Of course, the subtext of the biblical story is that God has promised Abraham that his descendants will inhabit the land. From the perspective of the biblical story, this is a promise about the future, since Abraham lived centuries before his descendants would conquer and settle the land. But for the authors living in the Second Temple period, this is really a reflection on Israel’s past, on a time when Judeans inhabited Hebron, which they characterized as the fulfillment of the divine promise to Abraham. At the same time, the authors are being realistic and telling their readers that for them, living in a different world, under the thumb of the Persians and surrounded by other peoples, they should follow their forefather’s example and live in peace with the neighbors.

The lesson here is that whatever one believes about divine promises and destiny, clashing is not the only response when two peoples have conflicting claims to the land. Another is to live beside each other in peace and mutual respect.

More than 2,500 years later, Jewish Kiryat Arba again sits astride a Hebron inhabited by a different people. Again, there are clashes. But the story of Sarah’s burial offers us another way. May we merit to see a time when, like Abraham and Ephron, each side competes to outdo the other — not in disrespect and violence, but in kindness and cooperation.

This article initially appeared in My Jewish Learning’s Shabbat newsletter Recharge on Nov. 11, 2023. To sign up to receive Recharge each week in your inbox, click here.