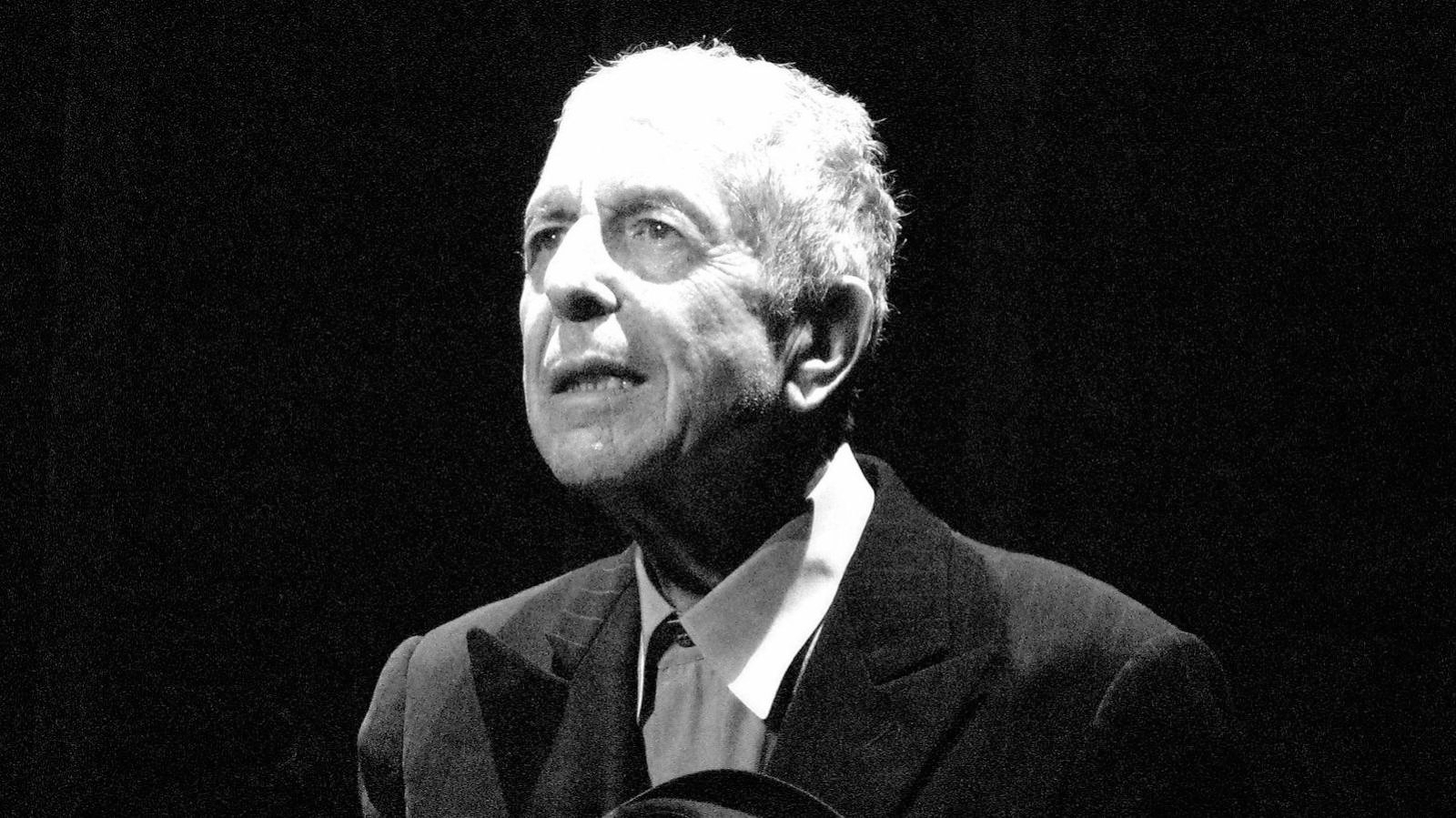

Note: Leonard Cohen died Nov. 7, 2016 at age 82.

The Montreal Jewish Community has produced a plethora of Jewish writers with unique literary expressions of Jewish identity, including A.M. Klein, Irving Layton, Mordechai Richler, and Leonard Cohen. Cohen was a poet and novelist, though he is best known as a singer-songwriter, with signature songs such as “Suzanne” and “Hallelujah.” Cohen grew up in a family deeply rooted in Judaism, living within a strong Jewish community, and from an early age he felt the burden of his name (kohen is a priest in Hebrew).

Like a bird on a wire

Like a drunk in a midnight choir

I have tried, in my way, to be free.

(“Bird on a Wire,” Songs from a Room)

Leonard Cohen’s Jewish Background

Leonard Cohen, dubbed by his critics as “the poet laureate of pessimism,” “the grocer of despair,” and “the godfather of gloom,”was born in Montreal in 1934. His maternal grandfather, Solomon Klinitsky-Klein, was a rabbi and a scholar. His paternal grandfather, Lyon Cohen, was a central figure in Montreal Jewish life who strongly believed that knowledge of Jewish history and letters and the performance of mitzvot (commandments) were essential for all Jews. Cohen’s childhood home was steeped in Jewish tradition: Sabbath prayers, regular attendance at the Shaar Hashomayim synagogue (presided over by his grandfather Lyon), and observance of Jewish holidays and ceremonies.

The Favorite Game, His First Novel

Given Cohen’s biography, his preoccupation with Jewish themes is not surprising, nor are the Judaic allusions often present in his poetry, prose, and songs. Cohen has always identified himself as a Jew, even when he became a Buddhist monk (“I’m not looking for a new religion. I’m quite happy with the old one, with Judaism,” he said). He has, however, expressed concern regarding the current state of Judaism. In The Favorite Game (1963), his first (semi-autobiographical) novel, Cohen expressed disillusionment with the superficial form of religiosity he observed through his protagonist, Lawrence Breavman:

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

He had thought that his tall uncles in their dark clothes were princes of an elite brotherhood. He had thought the synagogue was their house of purification…But he had grown to understand that none of them even pretended to these things. They were proud of their financial and communal success. They liked to be first, to be respected, to sit close to the alter, to be called up to lift the scrolls. They weren’t pledged to any other idea. They did not believe their blood was consecrated…They did not seem to realize how fragile the ceremony was. They participated in it blindly, as if it would last forever (pp. 123-4).

In this novel Cohen also deplores the contemporary ignorance of “the craft of devotion,” expressing his belief in the need for Jewish renewal as the only measure for survival: “Their nobility was insecure because it rested on inheritance and not moment-to-moment creation in the face of annihilation…The beautiful melody soared, which proclaimed that the Law was a tree of life and a path of peace. Couldn’t they see how it had to be nourished?”

The Prophetic Voice

Cohen expressed his views on “organized” Judaism again a year after the publication of The Favorite Game, while participating in a symposium held at the Jewish Public Library in Montreal. His speech encapsulated his views on the shift within Judaism from the truly spiritual and religious to the superficial and the material. Cohen expressed his belief that Jewish leaders had become more concerned with the corporeal, “nominal” survival of Jews as a group, rather than with the survival of their role as “witnesses to monotheism.” He regretted the disappearance of the prophet from Judaism, leaving only the priest.

Alluding to A. M. Klein as the last great Canadian Jewish poet who had tried to be both prophet and priest, he lamented the fact that Klein had “fallen into silence.” This silence was a warning, asserted Cohen, against “the rabbis and businessmen” taking over, against the replacement of the community’s humble buildings, “established by men who loved books,” with imposing edifices bearing plaques honoring not scholars and sages, but wealthy members of the community.

In a poem delivered that day, Cohen asserted that the comfortable, materialistic Jewish community was like a British square, but there was “nothing in the center”–only emptiness–as what the leaders of the community preserved was “themselves / their institutions, their charities / their state within a state.” Cohen insisted on the poet’s “old rich dialogue between the prophet and the priest” and on “the larger idea of community.”

Disillusioned by the establishment’s failure to address his concerns, Cohen found poetry (and later song) as his new form of prayer, the religious duty of priest inherent in his name transforming into that of poet.

Cohen’s Biblical Influences

Cohen has said that the Bible was the most important book in his life, that he felt privileged to know the “old tradition.”

His second book of poems, The Spice Box of Earth, published in 1961, is filled with allusions to the Hebrew Bible and to Jewish religion and customs — from the Sabbath (“After the Sabbath Prayers”) to the king and psalmist David and his beloved Bathsheba (“Before the Story”), the Messiah (“To a Teacher”) and the bondage of the Jews in Egypt (“Credo”) –indicating their prominence in Cohen’s literary imagination. Frequently, however, these influences mingle with Hellenism, fairytales, and Greek myth intertwining with Hebrew lore, all serving Cohen’s poetic endeavor.

“I’ve never been able to dissociate the spiritual from the practical,” Cohen commented in an interview, providing a useful explanation as to the choice of title for The Spice Box of Earth. The spice box, used in the Havdalah ceremony at the termination of Sabbaths and festivals, marks the distinction between the sacred and the ordinary. Poetry is, for Cohen, a form of prayer eliminating the boundaries between the spiritual and the practical, the religious and the secular, the sacred and the mundane. He seems to have dissociated God from the organized stream of Judaism he found unacceptable in Montreal, religion becoming “a technique for strength and for making the universe hospitable,” and God having no “evil associations or…organizational associations.”

Contemporary Psalms

In 1984, in the midst of a successful singing career, Cohen published Book of Mercy, a book of contemporary psalms addressing God with doubt and trust, praise and anger. For Cohen, God is both present and mystifyingly silent. When asked whether the Hebrew Bible had inspired the language of these psalms, Cohen replied: “That was just the natural language of prayer for me.”

The opening psalm delineates Cohen’s spiritual journey and relation to God, from a sense of absence and loss (“I stopped to listen, but he did not come”) to the gradual, hesitant return of God (“I heard him again…Slowly he yields. Haltingly he moves toward his throne”) and the re-affirmation of Cohen’s own role as a Jew, and as a poet: “In a transition so delicate it cannot be marked, the court is established on beams of golden symmetry, and once again I am a singer in the lower choirs, born fifty years ago to raise my voice this high, and no higher (p. 1).”

Cohen’s departure from religious practice did not stem from his objection to tradition, but from his disapproval of the state in which he found contemporary Judaism in Montreal. In fact, when he distanced himself from the Montreal community, living on the Greek island of Hydra, and was free to forge his own Jewish identity, he chose to observe the Sabbath regularly–lighting candles, saying the blessings, and refraining from work. Commenting on the importance of ceremony in everyday life, Cohen expresses his belief in patterns that had been developed and “discerned to be extremely nourishing,” as they represent a valuable reference “beyond the activity.”

The ultimate expression of Cohen’s Jewishness lies in the act of writing, as he expressed in a poem addressed to Irving Layton, his mentor and friend:

Layton, when we dance our freilach

under the ghostly handkerchief,

the miracle rabbis of Prague and Vilna

resume their sawdust thrones,

and angels and men, asleep so long

in the cold palaces of disbelief,

gather…

to quarrel deliciously and debate

the sound of the ineffable Name.

Layton, my friend Lazarovitch,

no Jew was ever lost

while we two dance joyously

in this French province,

cold and oceans west of the temple

. . .

I say no Jew was ever lost

while we weave and billow the handkerchief

into a burning cloud,

measuring all of heaven

with our stitching thumbs.

(“Last Dance at the Four Penny,” The Spice Box of Earth)

Carrying on the Tradition

In the documentary film Ladies and Gentlemen…Mr. Leonard Cohen, Cohen remembers his maternal grandfather, Rabbi Solomon Klinitsky-Klein, greeting him as a fellow writer, recognizing in him a kindred spirit carrying on the tradition in a spiritual, creative sense. Even in the remote province of Quebec, separated from Jerusalem by vast oceans, Cohen sees himself renewing his Judaism and contributing to Jewish culture and continuity.

While Cohen is a practicing Zen Buddhist, he sees no conflict between this and his Jewish observance. In February 2009, he was described in the New York Times as an observant Jew who keeps Shabbat, even refusing to give concerts on Friday nights. “I’m not looking for new religion,” he told the Guardian in 2004. “I’m quite happy with the old one, with Judaism.”

Concluding a performance attended by nearly 50,000 people at Ramat Gan Stadium in September 2009, Cohen recited–in Hebrew — the Birkat Kohanim (priestly blessing), originating in the Book of Numbers: “May the Lord bless you and keep you. May the Lord let His face shine upon you and be gracious to you. May the Lord look kindly upon you and give you peace.” As he raised his hands in the traditional formation for the blessing, known as Nesi’at Kapayim (the lifting of the hands), Cohen uttered its final word: “shalom.”

Cohen takes a religious, humanistic approach to the predicaments of the present. His own prophetic sense relates to impending social and political collapse, as seen in his song “The Future” (“I’ve seen the future, brother: it is murder”). Cohen does, however, find optimism even in imperfection, urging for perseverance and faith, despite the brokenness of everything around us:

Ring the bells that still can ring

Forget your perfect offering

There is a crack in everything

That’s how the light gets in.

(“Anthem,” The Future)

Note: Leonard Cohen died in 2016, after this article was written. Read his obituary here.

Havdalah

Pronounced: hahv-DAHL-uh, Origin: Hebrew, From the root for "to separate," the ceremony marking the end of Shabbat and the beginning of the week.