Commentary on Parashat Yitro, Exodus 18:1-20:23

After detailing the miraculous deliverance of the Israelites from the hands of their evil oppressors, the Book of Exodus catapults the hungry reader into Parashat Yitro, which includes the quintessentially defining moment of Jewish history–the Revelation at Mount Sinai.

In a fashion reminiscent of a multi-sensory Disney World ride, the text describes this historic encounter with unparalleled vividness. Harkening back to Abraham’s initial encounter with God in Genesis 15, the reader finds himself encircled by the darkest of clouds at the foot of a smoldering Mount Sinai. Yet despite the darkness, the text records this unprecedented event as a moment of total and absolute sensory awareness. So penetrating was the experience that the text actually records the participant’s ability to not only hear the thunder, but to “see” the sounds as well (Exodus 20:15).

Tradition has much to say about the way in which the ancient Israelites heard the experience of Sinai. According to one account, each word of the Revelation was heard as if they were all uttered simultaneously. According to another account, each Israelite heard the words of the Revelation differently, depending on his or her ability to comprehend the Divine message.

Hearing the Revelation

The ancient sages placed much emphasis on the “hearing of Revelation,” and this attention is underscored by their fascination with the physiognomy of our bodies and their concern for our ability to use and not abuse the power of speech and hearing.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Consider, for example, the explanation of the practice of piercing a hole in the earlobe of a Jewish slave who, when offered freedom, opts to remain with his master. According to a midrash, the piercing of the earlobe was a punishment for the slave’s failure to hear and heed the fact that God selected the Israelites as special servants at Sinai. OK, but why pierce the earlobe? If the punishment was intended as a reminder of the heavy price we pay for not listening, wouldn’t harming the eardrum have made greater sense?

Our sages answer this question by suggesting that the outer ear’s purpose is to serve as a funnel that collects sound waves and directs them to the inner ear. In this case, the shortcoming of the slave was not that he did not hear on Sinai that we are all to subjugate ourselves to God alone. Rather, he failed to hear that command as if it were directed to him, and him alone. His outer ear failed to funnel those words inside where they could be appropriately internalized, and as a result the outer ear bears the blemish as a constant reminder of its misdeed.

Understanding Cain

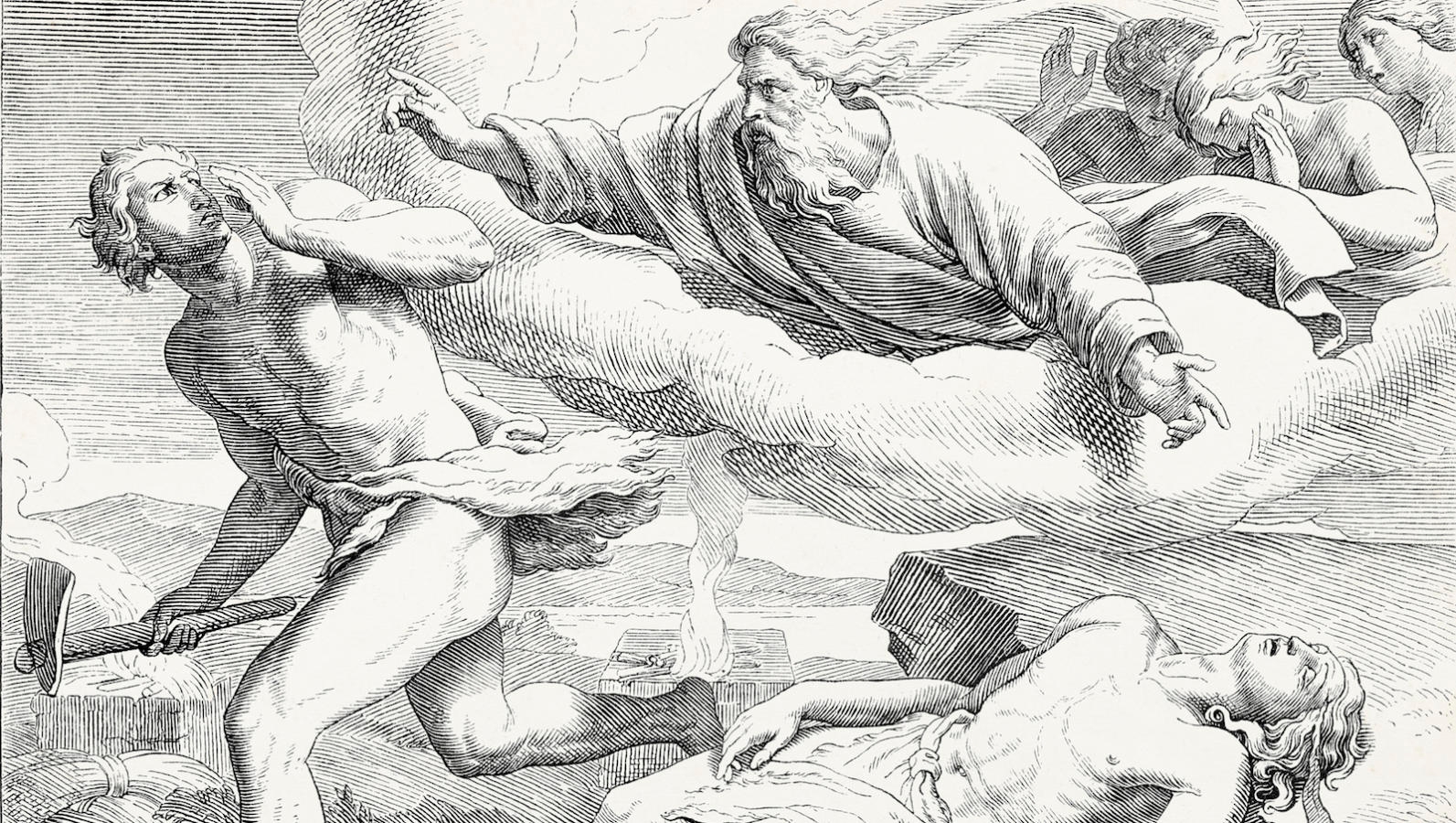

Another example of this theme is in the way the sages understand Cain’s motivation for murdering his brother Abel. The terse biblical text of Genesis 4:8 leaves much to the imagination. It simply states that Cain spoke to his brother and then killed him. But what exactly did he say that led to such a fateful outcome?

Ever on the lookout for opportunities to offer the reader positive rebuke, the sages suggest an all-too-human reading of this Genesis narrative. Cain is completely consumed by anger when his brother’s sacrifice is accepted by God and his own is rejected. Enraged, Cain finds himself unable to accept God’s reproof (Gen. 4:6-8) that was intended for him and him alone. Wracked with jealousy, Cain assumes that God told him this message in order that he could give over punishment to his unwitting and undeserving brother.

Thus, in an ironic twist, God’s intended rebuke of Cain actually stokes the fire of Cain’s hatred and contributes to an exchange that further enflames Cain’s animosity. Like most people, Cain held himself so guiltless that he was only able to hear the reproof as if it had been directed to everyone other than himself.

One more example comes to mind for how our sages unceasingly adjured us to speak and listen with greater measures of responsibility. According to a passage in the Talmud (Tractate Ketubot 5b), God designed our earlobes to be soft and flexible so that if one is around others who are speaking lashon hara (gossip and improper speech), one can bend the earlobe as an earplug to avoid listening to prohibited speech. The problem with this passage is that it conflicts with another Talmudic passage that uses the same rationale for explaining why our fingers are long and tapered. For that matter, the sages ask, why not just use your legs to walk away when you see others engaged in lashon hara?

The sages assumed that God wouldn’t have given us duplicate ways of accomplishing the very same task, and therefore they suggest a very clever solution to this apparent problem. They explain that there are three different types of lashon hara, and each one requires a different response.

There are those who speak lashon hara constantly, the professional gossips. One should have nothing to do with these people, and walking in the other direction when one sees them coming is the preferred response. The second type of lashon hara is that spoken by a basically good person, who from time to time slips into the trap of gossiping. The sages said this person needn’t be avoided entirely, and hence the preferred response is to simply distance yourself from the lashon hara by placing your fingers in you ears.

Yet there is a third type of lashon hara. If someone is asked for information concerning the honesty of a certain individual, and the question is asked by someone who is contemplating entering into a business relationship with the person in question, Jewish law is clear that the individual being questioned must respond and relate exactly what he knows.

However, if a third party is present, and he does not need to know this information, it is considered lashon hara with respect to him and he must not listen. Yet if he were to put his fingers in his ears, he would seem to signal that he believes the information is objectively lashon hara. This might wrongly discourage the one relating the information from continuing. So, by turning in his earlobe, the third party signifies that this information is lashon hara only with respect to him.

I close this d’var Torah with the blessing that each of us should be able to appreciate the majesty of Revelation as it was intended for us as a nation, as well as each of us individually. Attuning our ears to the words of Revelation and the life lessons passed down to us by our sages requires each of us to see ourselves as rings in a long chain of tradition.

Unlike the game of telephone we played as children, we must each take an active hand (and ear) in safeguarding the quality of the message we pass along to others. It is in this way that we prove ourselves worthy of the appellation applied to us in this week’s Torah portion: “A treasured possession…a kingdom of priests and a holy nation” (Exodus 19:5-7).

Provided by the UJA-Federation of New York, which cares for those in need, strengthens Jewish peoplehood, and fosters Jewish renaissance.

lashon hara

Origin: Hebrew, literally "evil tongue," slanderous speech prohibited in the Torah.