If you buy a new car, you will find in the glove compartment a thick paperback book called an owner’s manual. It will tell you everything you need to know to operate your car — what the knobs on the dashboard do, how to adjust the mirror, turn on your brights, engage the cruise control. Its job is to make operating the car as simple as possible.

But if the carburetor goes out or the fuel pump fails or a part is recalled, you’ll probably need to bring the car to a shop, where a mechanic will pull out a different thick paperback book, called a repair manual. Unlike the operator’s manual, which goes to great lengths to conceal the inner workings of the car, the repair manual shows its reader exactly how the car works in all of its complexity, with detailed drawings of each system and expanded views of every screw, washer, pin, and gear assembly.

Jewish tradition works the same way. The Jewish owner’s manual consists of those texts that help us use the tradition in everyday life. They are meant for consumers. These include the prayer book, the Passover haggadah, the High Holiday machzor, and even the Bible.

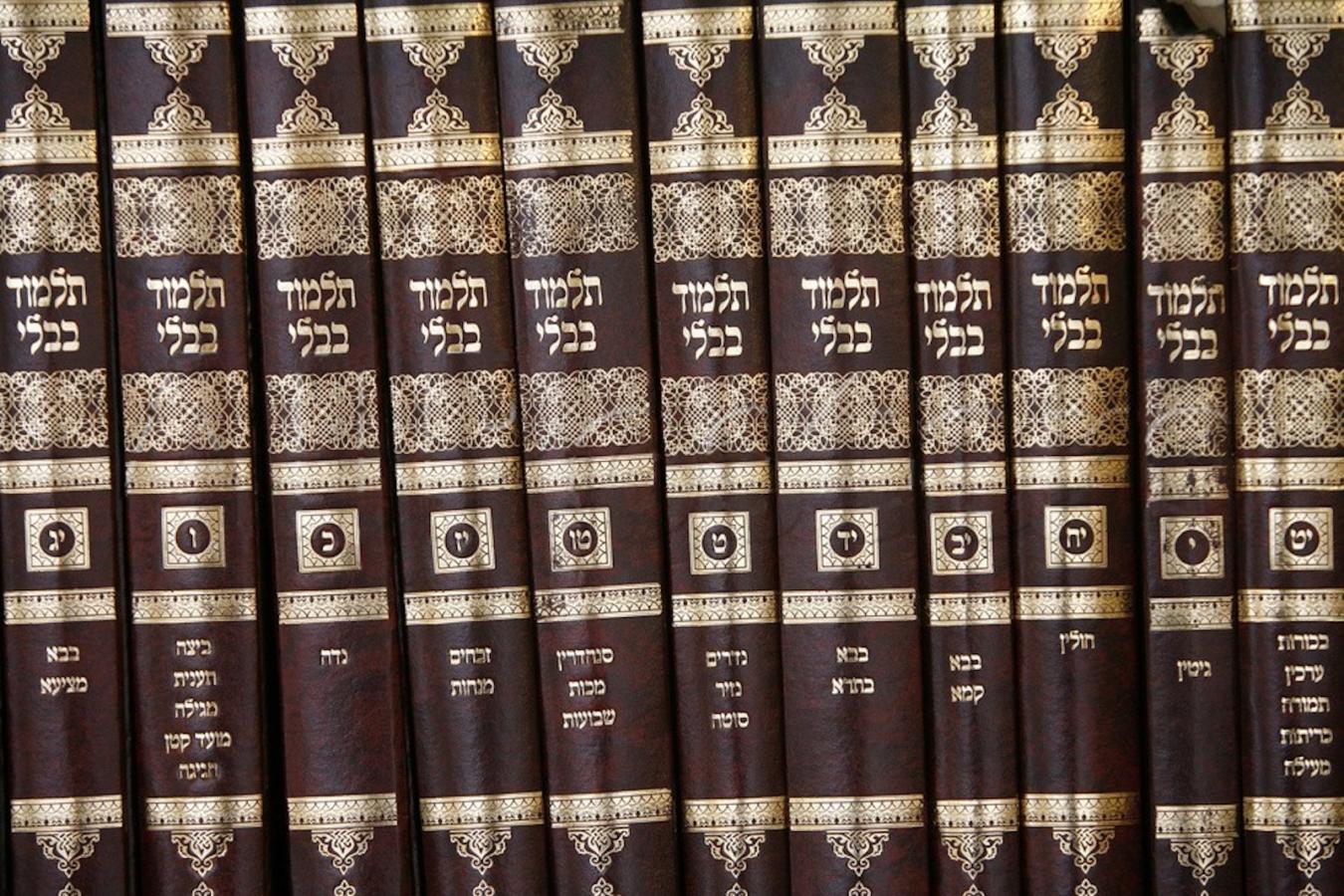

The Jewish repair manual are those texts that help us fix the tradition when it stalls on the side of the road. Like all technical manuals, these were initially intended not for the masses, but for the relative few who would devote their careers to getting under the hood of the tradition. For Judaism, that repair manual is the Talmud.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

The Talmud is not a code of Jewish law, though there’s plenty of law in it. Nor is it a collection of Jewish wisdom, though there’s a lot of wisdom in it, too. Nor is it a compendium of Jewish lore, though it’s chock full of stories. The Talmud is a manual for repairing, modifying, upgrading, and improving the Jewish tradition when components of it are no longer serving us well.

The Talmud’s creators understood that religious traditions exist to answer our basic human questions and to help us create frameworks to fulfill our basic human needs — the most important of which is the need to grow into the fully human beings we have the potential to become. They also understood that people grow and change faster than traditions do, so our traditions will inevitably stop working unless we have ways of tweaking them along the way — sometimes radically.

The Talmud is a curriculum for educating and empowering those who will do this kind of upgrading in every generation. It is the gift of the sages of the past to the sages of subsequent generations. “Listen,” they’re saying. “This is how we took the parts of the tradition we inherited that no longer worked for us and made them better. We don’t know what parts of the tradition will stop working in your generation, but we trust you to know that. Stand on our shoulders. Use our methodology. Be courageous and bold, like we were, and know that what you are doing may seem radical, but is deeply Jewish — and deeply traditional.”

This is the meta-message on every page of the Talmud. But to access it, you have to learn how to read deeply. Much of the discussion in the Talmud revolves around intricate cases of Jewish law, but that’s just the surface content. What’s being pointed to is not the details of the cases, but the legal principles and methodologies derived from them.

The Talmud, in fact, is no different from any legal casebook. In law school, students are required to buy casebooks — thick anthologies, elegantly bound, with gold lettering on their covers, that contain hundreds of historic, precedent-setting cases. There’s the well-known case in which a locomotive struck and killed a pedestrian at an uncontrolled street crossing, and the case of the tugboat that broke free of a dock and killed a sailor. But the point isn’t to teach about locomotives and tugboats, and no law student would think that it is. The particulars of these cases aren’t what ultimately matters. What matters are the legal principles derived from the cases. The goal is to teach the lawyers of the future how to think like lawyers — how to deduce principles that can be used in new cases, how to think in complex ways about new complex problems. The Talmud is doing exactly the same thing.

That might lead to the conclusion that the Talmud is the product of religious insiders, but in fact the Talmud records the voices of those who were on the margins of Jewish life during the late Second Temple and post-Temple periods — those who were both critiquing a Judaism that was failing and creating one that would work better. To do so, they invented and put into practice a system of mechanisms, principles, and rules-of-change that would guide them and future generations in the project of upgrading the tradition according to their new insights and lived experiences, one which might better serve the world of the future.

The core innovation that made this new system possible was the concept of svara — moral intuition. The sages of the Talmud named svara a source of Jewish law equal to the Torah in its power to overturn any aspect of the received tradition that violated their moral intuition or that caused harm that they could no longer justify, rationalize, or tolerate — even if it was written in black-and-white in the Torah itself. The sages’ trust in svara is what drives the evolution of the entire tradition and can be found on every page of the Talmud — if you know to look beneath the particulars of the locomotives and the tugboats.

And it is the refinement of the Talmud learner’s svara which is the Talmud’s ultimate goal. To paraphrase the philosopher Moshe Halbertal, the Talmud is not a normative document, but a formative document. It is designed not to tell us what our behavioral norms should be, but rather to form us into a certain kind of human being.

The text of the Talmud is intentionally pieced together in such a way that the very act of learning it becomes a spiritual practice unto itself, one which was designed to shape the learner into a morally courageous, empathic, resilient, flexible human being, one with the capacity to tolerate contradiction, paradox, complexity, and uncertainty. The act of learning Talmud is the Jewish tradition’s core spiritual technology designed to help the learner become this kind of person.

For two millennia, only Judaism’s mechanics and engineers had access to this technology. Only a small fraction of our community was empowered to utilize the spiritual, moral, and intellectual resources of Talmud study to become the kinds of people the Jewish tradition would have us be, and to bring our insights and life experiences to bear on the project of upgrading the tradition itself.

Today, for the first time in Jewish history, we have the opportunity, every one of us, to roll up our sleeves and participate in the creation of the Jewish future. The Talmud is a gift entrusted to every one of us by our Jewish ancestors who hoped we would find within it the tools to make ourselves, our tradition, and the world around us, better. So consider this an invitation to take a seat at the table where the tradition of the future will be created. By all of us.