The exiles who returned home from Babylon in 538 B.C.E. began plans for rebuilding the Temple, but adverse economic and political conditions delayed the project. Nothing happened until two prophets, Haggai and Zechariah, passionately pleaded with the people to continue and complete the building. Zechariah (his name means “the Eternal has remembered”) was active between 520 and 518, and the sacred task was at last taken up again and finished in 516-515.

Zechariah

According to Meyers (Anchor Bible: Haggai, Zechariah 1-8) “Haggai and Zechariah … must be given enormous credit for using their prophetic ministries to foster the transition of a people from national autonomy to an existence which transcended political definition and which centered upon a view of God and his moral demands.”

We know nothing about the personal life of the Prophet (Zechariah), except that he was the son of Berachiah and the grandson of Iddo. We have only the book that goes under his name, and it happens to be one of the most difficult in the Tanakh. Rashi and Ibn Ezra long ago noted its problems, which are exacerbated by a clearly visible difference between the first eight chapters and the last six. It appears to many scholars that chapters 1‑8 are by one person (called First or Proto‑Zechariah) and 9‑14 by another (called Second or Deutero-Zechariah).

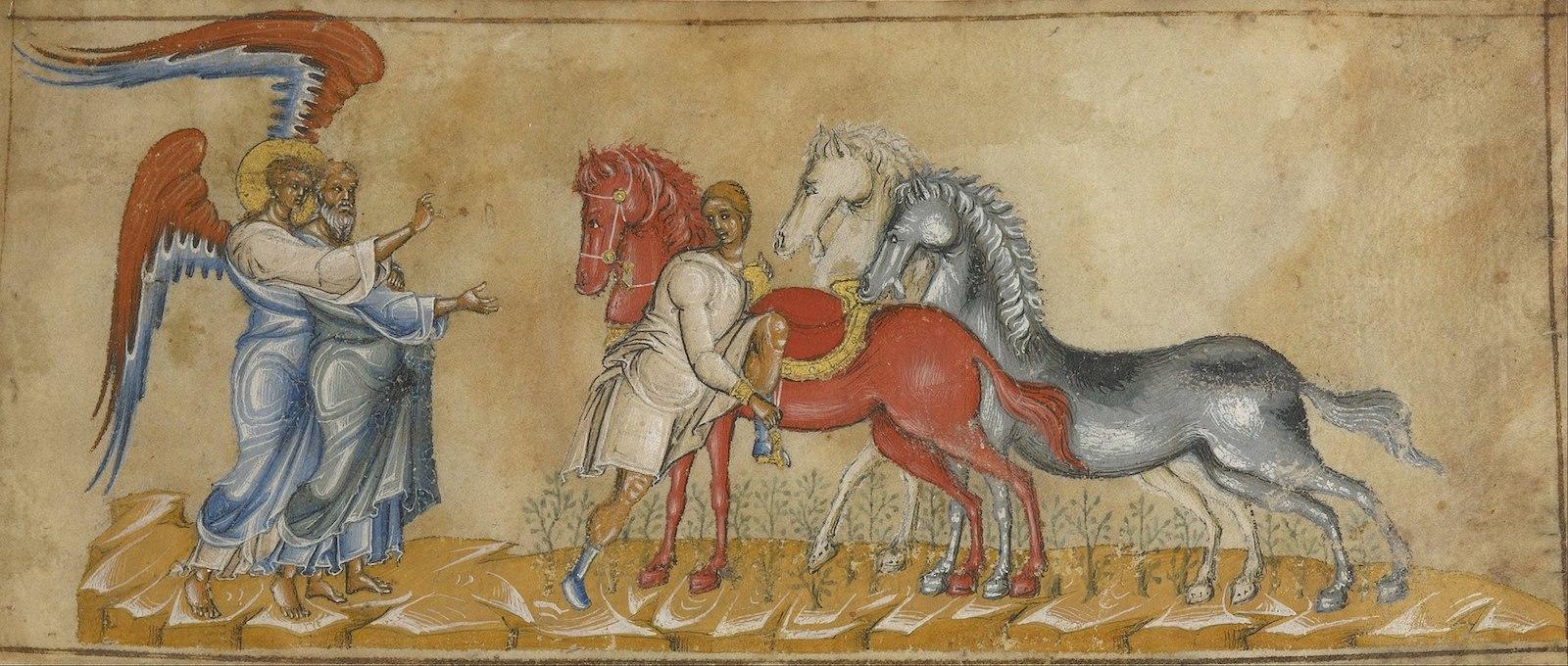

The former relate eight visions suffused with angels and other rich symbolism, with ethical pronouncements and a spirit of hope. These chapters also take note of the two most important personages of Yehud (Judah), the high priest Joshua and the governor Zerubbabel, a descendant of the House of David.

A Second “Zechariah”

Chapters 9‑14 (of Zechariah) lack most of these features. Instead, they contain a series of pronouncements against other nations and prophecies about the end of days. The Temple is not mentioned (probably because it was already completed); and where the First Zechariah extols the governor, the Second Zechariah heavily criticizes him. The fact that Greece (yavan) is mentioned suggests that this portion of the book was written after the time of Alexander the Great (died 323 B.C.E.).

But the controversy has not been fully resolved, and there is a renewed tendency to see the two parts of the book as having a closer relation than was previously assumed.

Malachi: The Last Prophet Urges Revival and Reconciliation

Malachi stands at the end of the prophetic books in the Tanakh, and tradition held that after him prophecy ceased in Israel. He thus represents a watershed in the development of Judaism: until then, God would speak to selected individuals and charge them with a mission to exhort and predict. But from then on, humans and not God would identify the truth. They would be called soferim (scribes) at first, because they belonged to those who guarded the literary tradition of the people, and later were known as rabbanim (rabbis), whose primary function was to teach and elucidate God’s law.

We do not know Malachi’s identity; the name simply means “My (that is, God’s) Messenger,” although some ancient sources identified him as Ezra and others as Mordecai. The whole spirit of the book suggests that the Temple had been rebuilt (516-515 B.C.E.). Yet it also suggests the disappearance of the enthusiasm shown during the building. Malachi describes a priesthood that is forgetful of its duties, a Temple that is underfunded because the people have lost interest in it, and a society in which Jewish men divorce their Jewish wives to marry out of the faith. The Prophet lived probably sometime after the year 500, perhaps as late as 450 (B.C.E.). It was an era of spiritual disillusionment, for the glorious age that earlier prophets had foreseen had not materialized.

Malachi urges his contemporaries to engage in a religious revival. Remember God and Torah, he tells them; make the Temple once again a center of your affection and attention; and purify your family life. The very last lines of his book speak of the “great day” that will bring reconciliation between the generations–and with this old-and-modern challenge he leaves us:

Malachi 3:23-24

Behold, I will send you Elijah the prophet,

before the coming of the great and terrible day of the Eternal,

To turn the hearts of parents to their children,

and the hearts of children to their parents–

lest I come, and smite the land with destruction.

Excerpted from The Haftarah Commentary (URJ Press)

Haftarah

Pronounced: hahf-TOErah or hahf-TOE-ruh, Origin: Hebrew, a selection from one of the biblical books of the Prophets that is read in synagogue immediately following the Torah reading.