Commentary on Parashat Terumah, Exodus 25:1-27:19; Numbers 28:9-15; Exodus 30:11-16

Speak unto the children of Israel, that they bring Me an offering; of every man that giveth it willingly with his heart you shall take My offering. (Exodus 25:1)

Among the 613 mitzvot (commandments), that of donating precious possessions for the building of the Tabernacle in Parashat Terumah stands out for its element of volunteerism, which places it outside of the usually clear-cut nature of halacha(Jewish law). A donation for building the mishkan (tabernacle) not only isn’t compulsory, but it becomes a donation worthy of God’s approval only when it’s spurred by a spirit of freedom and generosity of heart: “every man that giveth it willingly.”

What Is the Mishkan?

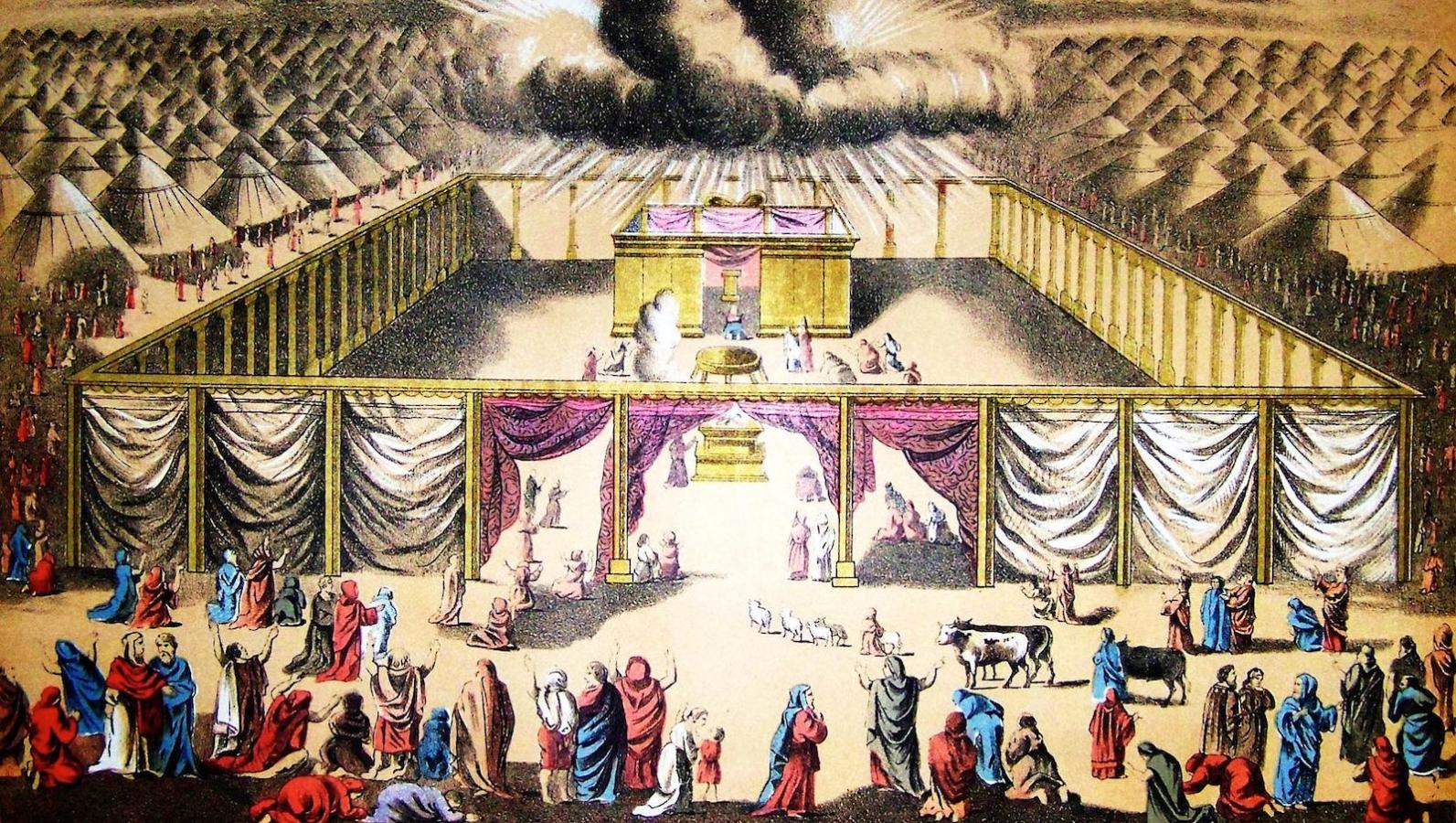

What is the mishkan, and what about it demands this act of pure volition? The portable precursor to the Temple is roofless; like a tent in the desert, it’s covered only by goatskins. Its interior is more elaborate, with the aron ha-brit (Ark of the Covenant), luchot ha-brit (Tablets of the Covenant), menorah, shulchan (table), golden altar, and other priestly garments and accessories. How amazing that 450 verses in the Torah are devoted to this structure!

We may better understand the purpose of the mishkan by viewing it against the backdrop of God’s creation of the universe. The Creation and Garden of Eden narratives indicate the Torah’s interest in the variety of interrelationships between God and man: their nature and dynamics, expectations and disappointments, times of stability and periods of exile.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

From this perspective, the mishkan has a crucial function. While the creation of the universe was a divine act intended for humans, the creation of the mishkan was its complement, a human act directed toward the Creator of the universe, inviting Him to find a place in this world. God wants man to create space for Him within his vast universe: “And they will make for Me a sanctuary, and I will dwell among them” (Exodus 25:8).

This idea of a human home for God is by no means easy to grasp. A midrash [commentary] (Tanhuma Ki-Tissa 10) notes:

Three things that God said to Moses frightened him. One was, “When God said to Moses,’and they will make for me a shrine,” he questioned: “Oh, Mighty One, is it not written, Behold, the heaven and the earth cannot contain Thee (I Kings 8:27)? How then can You say, they will make for Me a sanctuary?”

Interestingly, the midrash has Moses quoting the words of King Solomon, who voiced them at the time of the dedication of the Temple in Jerusalem, 500 years after the mishkan was built.

Later, the midrash refers to another question asked by Solomon, which is again attributed to Moses: “But will God indeed dwell on the earth?” (I Kings 8:37) The midrash continues with God’s answer, “…Not as you comprehend it, with 20 planks northward and 20 southward and eight westward — rather, I will descend and reduce My divine presence and furthermore, I will reduce it into a square cubit!”

This mind-boggling paradox — to worship Him whom “the heaven and heaven of heavens cannot contain” within the confined space of a square cubit — heightens the tension innate in the concept of worshipping God within any spatial limit. A beautiful talmudic saying expresses this paradox in romantic terms: “When our love was great, we could lie together on the point of a sword. Now that our love has ceased to be strong, even a bed of 60 cubits is too small and does not suffice.” (Tractate Sanhedrin 7a)

Perhaps this is the role of the mishkan, to be “the point of the sword,” where God may reside when there is love. In our parsha, the love between the Jewish people and God that sustains the mishkan is concretized by the “willingness of heart” that God requests and the people provide.

Why Even Build It?

But why did God want the people to build a mishkan in the first place? Commentators disagree whether the mishkan was part of God’s original plan for His people, or was a consequence of the people’s attempt to “concretize” God through the sin of the golden calf. According to the latter outlook, the real essence of religious experience is the perception of God as being omnipresent; that is, one can experience God anywhere, rather than His being confined to one place.

Thus, Sforno, a medieval commentator, claims that there was no need to anchor the worship of God to a concrete place, because the experience of hearing — and even seeing– God’s voice at Mount Sinai would have provided the paradigm for other encounters with Him. But, continues Sforno, after the sin of the golden calf, the need arose for a more tangible means of worshipping God; thus, the mishkan and its furniture, implements, and rites.

The opposing view regards the mitzvot concerning the mishkan and the Temple as laws that God intended to give from the beginning of Creation, so as to reduce Himself to be able to inhabit this world, to rest in a house in which He would meet His worshippers. According to this view, the concept of makom (place) has great significance for Judaism, as reflected in the designation of Jerusalem and the Holy Temple as “the place.” In addition, one of God’s names is Makom.

Today, in the post-Holocaust world, we Jews face the deep challenge of reformulating our relationship with God. To this day, two very different conceptions of Jewish faith exist — one viewing God as tied to a makom, the other seeing Him as ein-sof, without place.

In our time these differences can serve as a basis for a new theological dialogue. In Israel, the view of God as residing in a holy place, and the religious experience of holiness of place, is often intensified. However, this very view also has served as a source of bitter conflict.

Conversely, the largely abstract, “place-less” conception of God often found in the Diaspora can be a source of tremendous religious intensity and impel unique spiritual quests. But it also may limit Jews? ability to experience a more concrete image of God as residing in a defined place.

A meaningful dialogue between these two viewpoints would help us achieve a broader perspective of our faith and, specifically, better understand God’s place in our world. It may even help us advance our efforts to reach real shalom (peace), which is another major attribute of God. In the words of Rabbi Yehoshua: “Great is peace, for the Holy One Himself is called Peace.” (Midrash Sifra, Leviticus)

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.